Master of Satire

Issue 1/1981 | Archives online, Authors

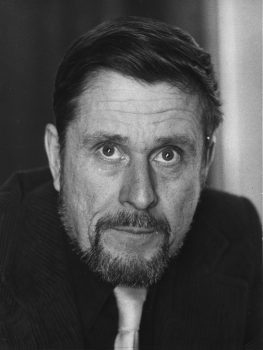

Henrik Tikkanen. Photo: Schildts & Söderströms

Henrik Tikkanen (born 1924) comes of a cultured Swedish-speaking family: his father was an architect, his grandfather an eminent art historian. But it is not only linguistically that Tikkanen belongs to a minority: in a land famous for epic he expresses himself in epigram and satire; in a land of lakes and forests he is an unashamed city-lover; in a land addicted to military virtues he stands out as a pacifist; in a land of books he writes for the newspapers. And in one of his autobiographical novels he confesses that he lacks the sentimental streak that motivates everything that is ever done in Finland.

For a Finnish author, Tikkanen has an exceptionally close relationship with the daily press. He earned his living as a working journalist, initially with Hufvudstadsbladet, the leading Finnish newspaper in Swedish, and later with Helsingin Sanomat, the biggest of the Finnish papers. After serving in the war it became his ambition to be Finland’s ‘best and only’ newspaper artist: he certainly achieved it. As a columnist and documentary feature writer who is at the same time a brilliant wit and coiner of epigrams, and who illustrates his own text, he still has no equal; indeed it would be hard to think of anyone who could even rank as a competitor.

Since 1946 Tikkanen has written and illustrated a whole series of travel and milieu books. He has travelled with an observant eye in Europe, America and the Soviet Union. One of his best books in this category is Dödens Venedig (‘Doomed Venice’, 1973 ): conceived as a description of a city threatened with destruction by air pollution and land subsidence, it can be read as a criticism of the destructiveness of our so-called civilisation. For his books about Finland, the settings are provided by Helsinki and the offshore islands. Mitt Helsingfors (‘My Helsinki’, 1972) describes the history, background and life of his native city, while the life-style and surroundings of the Swedish-speaking islanders are recorded in Min älskade skärgård (‘My beloved islands’, 1968 ).

‘Helsinki Quartet’

It took some time for Tikkanen to be accorded proper recognition as an author. One reason may have been that in Finland newspapers are not normally regarded as a medium for literature. The tide began to turn in 1975: in the spring of that year he won the prestigious Eino Leino Prize, and the following autumn saw the publication of Brändövägen 8 Brändö Tel. 35 (‘Number eight Brändo Way, telephone three-five’), the first of a series of more or less autobiographical novels or memoirs. This won him a State Literature Prize. Further volumes, each with a different Helsinki address as its title, followed in 1976 and 1977, after which the series began to be known as the ‘address trilogy’. When an unexpected fourth volume, Georgsgatan, appeared in 1980, the series inevitably became the ‘Helsinki Quartet’. Reviewers compared the author to Swift, to Voltaire, to Strindberg; but in some Finland-Swedish cultural circles the books have aroused more than a little resentment. Tikkanen, with immense candour and pitiless mockery, documents the decay of his own upper-class family and community, sparing neither himself nor his relatives and friends. Recession, war, alcoholism, a self-indulgent life-style and an increasingly democratised society have swept away most traces of the former upper class. The principal themes of the volumes are family, war, marriage and illness. Tikkanen’s passion for life rises superior to all the opposing forces. He says he wanted to show Death what a tough opponent it had taken on. In the last volume Tikkanen’s exhibitionism and nihilism are less marked: he even admits the possibility of a Supreme Being. After winning critical approval in Sweden, the first volume appeared in an English translation (Snobs’ Island, translated by Mary Sandbach, Chatto and Windus, 1979 and A Winter’s Day, Pantheon).

Anti-war satire

Tikkanen belongs to a generation to whom the experience of war came during their most impressionable years. War was for him a truly horrifying experience. In one book he describes how he shot himself in the hand so as to get away from the front. The trauma of war colours Tikkanen’s whole view of the world: in his works war is a constant theme, opposition to war a constant message. The novel Hjältarna är döda (‘The heroes are dead’, 1961) is about young Helsinki men returning after the war, the difficulties they have in adapting themselves, their thirst for life. Ödlorna (‘The lizards’, 1965) is a gallery of pictures illustrating the senselessness and cruelty of war.

Tikkanen says in one of his memoir-novels that he has never managed to liberate himself from the reality of war. There may thus be an autobiographical aspect to one theme that has clearly fascinated him, that of the forgotten soldier, continuing to fight the war long after peace has been declared. The idea may have been suggested by a case reported in the press some time in the 1970s, when a group of Japanese came to light in the Philippines, still unaware that the war had ended. In its first version, Unohdettu sotilas (‘The forgotten soldier’, 1974), Tikkanen’s story describes the one-man war waged by private Vihtori Käppärä against civilians and peacetime officials in the forests of Karelia. In 1977 he re-wrote the work as 30-åriga kriget (‘The Thirty Years’ War’, French transl. Les Heros Oublies, Pandora,1980). In a sequel, Efter hjältedöden (‘After a hero’s death’, 1979), we can read of Käppärä’s adventures in the world of today.

This idea of the forgotten soldier is a brilliantly simple vehicle for anti-war satire: effectively and instructively, the situation dramatises the incompatibility of peacetime and wartime values. Between Käppärä and peacetime society there is an unbridgeable communication gap. At the same time Tikkanen is able to bring out the unreality of the so-called peace prevailing today: the world of war preparations, localised wars and cold wars are to Käppärä all too painfully familiar. The soldier is portrayed with gentle irony, as the victim of war rather than its representative. It is a child-like innocence that makes him continue carrying out a military order for thirty years, and it is the same innocence that leads him finally to the ideal of peace. The old warrior becomes famous at home and abroad as a public speaker, advocating a United Nations Army as the only road to peace. It is the same solution that Tikkanen himself propounds in the last of his memoir-novels. Käppärä eventually becomes such a threat to those who live by and for war that he has to be eliminated by assassination. In 30-åriga kriget, an extract from which appears below, Tikkanen employs his entire satirical armoury against war and military thinking, merciless to priests, bishops, politicians and psychiatrists alike.

But the author’s underlying optimism also makes itself felt: even after a lifetime of being manipulated, Private Käppärä (or, if you like, the soul of the nation) achieves a total moral victory over the mighty machinery of war.

Translated by David Barrett

Tags: classics, Helsinki, satire, travel, war

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Markku Envall

Aphorisms - 31 December 1986

The aphorism reborn - 31 December 1986

-

About the writer

Markku Envall (b. 1944) is an author and literary scholar. He was awarded the Finlandia Prize in 1989 for Samurai nukkuu (‘The Samurai is sleeping’), a collection of aphorisms. In addition to aphorisms, Envall has published essays, poetry, radio plays, a novel and academic studies.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.