Teemu Kupiainen & Stefan Bremer

Music on the go

3 March 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

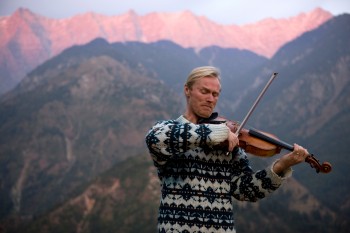

A little night music: Teemu Kupiainen playing in Baddi, India, as the sun sets. Photo: Stefan Bremer (2009)

It was viola player Teemu Kupiainen‘s desire to play Bach on the streets that took him to Dharamsala, Paris, Chengdu, Tetouan and Lourdes. Bach makes him feel he is in the right place at the right time – and playing Bach can be appreciated equally by educated westerners, goatherds, monkeys and street children, he claims. In these extracts from his book Viulun-soittaja kadulla (‘Fiddler on the route’, Teos, 2010; photographs by Stefan Bremer) he describes his trip to northern India in 2004.

In 2002 I was awarded a state artist’s grant lasting two years. My plan was to perform Bach’s music on the streets in a variety of different cultural settings. My grant awoke amusement in musical circles around the world: ‘So, you really do have the Ministry of Silly Walks in Finland?’ a lot of people asked me, in reference to Monty Python.

In 2002 the first trip during my grant period took me to France, Spain and Portugal, where I performed in small villages in the mountains. When, on the outskirts of a small French village, I plucked up the courage to perform all of Bach’s violin sonatas and partitas from memory for the first time, my one and only listener was clearly enthralled. This I deduced from the way in which it kept jangling the bell tied around its neck throughout the duration of my two-hour performance. As soon as I began to play, this lonely cow came up to me and did not walk off at any point. I thought of this as a good omen.

In autumn 2003 I travelled to China, and from there I continued to India, then Morocco. Finally, I made a less adventurous trip to Lourdes in France. Of course, there were plenty of shorter trips in between these, but on those trips I didn’t keep a diary.

For me, playing on the streets is not about background music; these are concerts – in fact, they are almost more than concerts. I often play for a single listener or just a handful of listeners at a time. As an experience, this is far more intimate than a normal concert, more challenging, and with that comes a greater sense of responsibility. Often, particularly at the beginning of my trips, I can be very nervous as I step out into the street, and sometimes, as the first people stop to listen, I have had some sort of blackout and been unable to remember how the music continues. Such a thing hasn’t happened to me in a concert hall for years. For this reason, I practice a lot on these trips, at least as much as I would when preparing for a ‘normal’ concert.

In addition to playing on the streets, these trips involved another one of my passions: Johann Sebastian Bach and his suites for violoncello and his sonatas and partitas for violin. All of these works can be played on the viola. Only a viola player can set himself the challenge of playing every one of Bach’s suites, sonatas and partitas from memory in a single concert. Only a megalomaniacal viola player, that is….

January 19, 2004, Shimla, India

No matter how badly you sleep in a dingy, mouldy hotel room, waking up as the sun rises and seeing the summit of the Himalayas from your window more than compensates. Three hours’ morning practice on the violin sonatas. Yoga. Then out on to the street.

The centre of the old town is built on a steep ridge. On top of The Ridge there is a street, at the end of which is a market square with a church at one side. Bach and a church! I set up nearby. I feel nervous – not about my own ability, but because of the potential indifference.

An hour’s set turns into a two-hour set. Throughout there are a couple of dozen people standing around, listening intently. Between every movement someone always wants to chat. ‘Where are you from? What is your good name, Sir?’

I have to start playing the movements very attacca, without a break. Four reporters turn up, each with their own photographers. One national newspaper and three local ones, who all claim to be the largest in the region.

And the questions! ‘Shimla is the gateway to God. How do you feel this when you are playing? How does your music explain the mysteries of the universe? What is your aim in life and can you achieve it by playing? How does your music affect you as an individual? What about society as a whole?’

The most challenging exam of my life. Puzzling. People get straight to the point here; they don’t feel the need to warm up with empty chitchat. These questions make me think hard. Will this trip provide me with answers?

During the Sixth Suite a young man with a mouth organ sits down next to me and starts playing along with Bach’s harmonic progressions: G major, D major. When I finish, he begins to play some local melodies. I accompany him: C major, G major.

Lunch. I have decided to become a vegetarian for the rest of the trip. This is the easiest solution all round, and besides, vegetarian food here is very good. During my students years in Cologne I think I was a vegetarian for two years, because vegetarian food there was cheap. I could do it in Finland too, if finding good vegetarian food were as easy as it is here.

After lunch I go for a walk. I continue up The Ridge. A warm hillside. I see four eagles; one of them is circling barely 50 metres from where I stand. The city of the temple of the monkey god is full of monkeys. The eagles presumably fly up here from further across the mountains for a meal of roast monkey. I sit down to watch the flight of the eagles and start playing. I try to play in a way that mirrors the contours of the eagles’ flight: long lines, allowing the music to carry my thoughts, just as the eagle rests on the mass of warm, buoyant air.

There are never many listeners at any one time. Having said that, almost every other passer-by stops to listen for a moment, some for rather longer. During the Fifth Suite the sun goes behind a cloud; it turns cold and even the eagles disappear. Still, I manage to get to the end of the Sixth Suite without going into a tailspin, though I can’t help getting the sense that this is something of a forced landing….

January 22, Dharamsala

Slept for twelve hours! Three hours of practice, then yoga. I go to visit another masseur. In fact, I tried to reach this Tibetan-Chinese acupuncture masseur yesterday, but he wasn’t in. This time I go to make an appointment and am shown straight on to the massage table. Thumbs start kneading my buttocks.

‘Does this hurt?’ Yes, it hurts.

‘And here? What, it doesn’t hurt? What about here?’ Yes, it hurts.

The doctor convinces me to let him use one small needle. I manage not to faint. I try to think of it as a mosquito – after all, I let them bite me and eat in peace. After the procedure I feel much better, but maybe I’m just happy at overcoming my fear of needles and surviving the jab.

Later that afternoon I go back to the church. A young Irish couple is sitting outside. We chat for a while. All of a sudden the girl starts to laugh: ‘You must be the Finnish musician!’

The couple has already been in the village for a month taking part in a reiki healing course. That morning the girl opened a newspaper for the first time in a month, the national English-language newspaper The Times. It featured a photograph taken in Shimla showing me playing to street children. A short article said that I was travelling through the mountains. The girl said she’d thought that it would be nice to meet me. And now here she stands, giggling, and says that life is like a Kieślowski film.

Living in the local area there are four Christian families and a priest. An elderly gentleman standing outside gives me permission to play in the church. He says that the priest will be arriving soon. I play for half an hour for the Irish couple and the odd tourist.

The priest arrives. He quizzes me about what happened the day before. ‘Between four and five o’clock? Oh, so the door was open? You didn’t see anyone?’ Long pauses between each question.

Then: ‘Listen. Someone broke in here yesterday: our collection box was stolen. The window was smashed in. The big chain on the door was broken and that’s where they got away with the collection box. Don’t tell anyone you were here yesterday or you’ll be talking to the police for goodness knows how long.’

Okay! Got the point.

Then we agree that I will play in the church every day between three and five. Everyone is welcome to come and listen.

A little more playing followed by a yoga course for beginners – disappointing. Even the preliminary positions are so complicated that it will take years of practice for me to get into them.

Tibetan food.

Apparently the Dalai Lama arrived here this morning. Every now and then he gives public lectures in English. Suddenly the lights go out. My Tikka head lamp – what a marvellous purchase! These mountain storms are strange. The temperature is hovering around zero but there’s still plenty of thunder. The curtains billow in the gusts of wind, though the windows are shut. We won’t run out of air. It feels good to be here.

January 23, Dharamsala

It’s early afternoon; I’m shivering beneath the blankets. The electricity comes on and off. Outside it’s sleeting. Still I managed to get in three and a half hours’ practice this morning. As I was practicing, I realised that in my imaginary practice session early that morning I had been playing some wrong notes. My pitching was a bit sketchy.

After practicing I do some yoga to warm up. Instead of doing the two-hour walk I have planned, I crawl back to bed. If only it would clear up. The kilometre-and-a-half walk to the church really doesn’t appeal.

It brightens up just before three o’clock! Clothes on then straight to the church. The snowline is 50 metres up the hill from where I am staying. 200 metres before the church it starts raining hailstones. I run to the church. Ten minutes’ warm-up. Eventually my hands are warm enough that I dare to start playing. Of course, there is no heating inside the church and the doors are always wide open.

My playing is almost going well. My audience consists of the priest, who is busy sweeping the yard, and a woman washing the floor. During the last piece, at the most difficult part of the fugue in the Third Sonata, the first outside listener arrives. Almost immediately I lose my concentration, so much so that I can’t get to the end of the fugue. After about ten attempts and a lot of fumbling around, I finally finish the movement on the wrong chord. Deeply embarrassing. Thankfully the final two movements seem to go smoothly enough. When you’re that ashamed, at least you don’t feel the cold. Before playing tomorrow, practice the fugues ten times!

I get a gig – as a photographer. The priest asks me to come back to the church the next morning to take photographs of a visiting bishop.

That evening I take my viola with me to dinner. There are people at two other tables in the restaurant. They ask me to play. We chat. At one table is an Indian reporter with Reuters, at the other the Tibetan reporter for an American company. In only a few days in India I’ve met more reporters than in the last ten years in Finland! The Tibetan wants to do an interview. I ask to see the questions in advance, because I know we’ll end up talking about politics. Now isn’t the time for silly jokes.

The next day I will see a student. A 17-year-old local boy had heard someone playing the violin and had liked it so much he had got himself a violin. To his disappointment, he so far hasn’t been able to get a note out of it. He may be even more disappointed once he does get a note out of it.

January 24, Dharamsala

The boy isn’t disappointed at all. The violin is terrible. It takes me half an hour just to put the strings in the right place across the bridge and the nut. Then I show him how to lift his hands, how to use the weight; how to hold the instrument and the bow. I try to explain what it should feel like.

Ten minutes later the boy can play a two-octave G major scale in tune, then A major; easy nursery rhymes; half an hour later even Frère Jacques. Soon our lesson is over.

By far the most talented beginner I’ve ever met. He says he has played the guitar, but even so! I could have taken photographs of the position of his hands and used them as teaching material. Tomorrow the boy and his friends are going to play me some local Tibetan music….

January 25, Dharamsala

This morning I walk up as far as the snowline; it’s now at an altitude of about a couple of kilometres. The sun is just rising. Utterly still. From the other side of the valley I can hear the sounds of a religious mass. I find a sunny opening in the hillside forest and start to play. Three pine martens and four long-tailed parrots come to watch. The sun warms me and the air is fresh. Two such glorious mornings in a row!

About two hundred metres beneath me there is a road, about a hundred or so passers-by every hour. Almost all of them stop and turn their heads in bewilderment. Where is that music coming from? This instrument certainly has a very powerful sound; all you need is a decent concert hall.

More treatment for my sciatic nerve. The Tibetan acupuncture masseur I visited before gives me five needles in the buttocks and one in the neck. It’s ridiculous to be so scared of it, but I’m scared nonetheless.

I give an interview to the Tibetan reporter. As I suspected, every question has a political edge to it. He promises to send a draft of the article to my email so I can check it through.

Then more street playing in the same spot as yesterday. An old monk listens to almost the entire set, using his cane to shoo away curious people stopping in cars or on their motorbikes. Another person to stop is a Canadian convert. He moved here six months earlier after selling all of his possessions, including a large collection of Bach recordings. He knows all the Suites. He almost starts to cry with joy upon hearing his favourite music for the first time in months. He thanks my teachers. I join him in thanks.

That evening, back at the hostel in the cultural institute, my student who has just got his hands on a violin plays at least five different instruments – that must explain why he is such a quick learner. The hostel is home to 35 artists, all of whom can sing and act and play several instruments. On top of all that, my student still wants to learn to play the violin!

Tomorrow is Indian Independence Day. The festivities have already begun. In the distance I can hear the pounding of a bass.

January 26, Dharamsala

This morning I pack my things and pay my hotel bill: 19 euros for five days including hot water, heating and laundry. Then it’s out into the streets.

With the exception of my first day in Shimla, I’ve been playing with my viola case closed. There are plenty of people who need money here – far more, in fact, than in the poorest areas of China that I’ve ever visited. But this time I decide to play next to the beggars with my case open. I have made myself a little sign: For milk powder and rice. Thank you.

I play two of the Suites. Only one person stops to listen. Then some traders come out and shoo me off their patch. Is it because of my sign, or is it just one of those days?

I go back to make corrections to the interview by the Tibetan reporter. Sitting at the computer time flies past, and I forget that I have an appointment to keep. I have promised an earnest-looking shoeshine boy that today, the day I was to leave, I will meet him at twelve o’clock and buy some milk powder and rice for him and his younger sister.

I arrive sixteen minutes late. The boy is nowhere to be seen. Every day he has looked me up and asked: ‘Promise?’ I always reply: ‘Promise.’ And after all that, I don’t turn up.

I wait for the boy until one o’clock. He doesn’t show up. I give three beggar women the money I have reserved for milk powder and rice. What a mistake! I should have waited until I was about to get on the bus. Groups of beggars run up to me as though they have some kind of telepathic connection, pulling at my clothes and hanging from my limbs. And the women, to whom I gave the money, think it was not nearly enough: one of them tries to snatch all of the money from my wallet.

I dash into a nearby restaurant and don’t come out until the alley looks empty. But the beggars are still waiting. The flock gathers again in under a minute. I escape outside the village. Only once I reach the temple do the most determined of them finally give up.

I walk up to the clearing I found before. Again I see an eagle soaring overhead. I sit down to warm myself in the sunshine. I am reminded of someone I was at school with for twelve years. After she died she appeared in my dreams and introduced me to an eagle. ‘The eagle is your friend now; it will show you the way.’

Then there is the shoeshine boy. I gave him a solemn promise to show up. This ten-year-old boy, who has double-checked this important matter with me many times over, only waited a minute or so at our meeting place. He was clearly unable to take the disappointment of being let down by the rich tourist. And now he’s gone… I feel awful.

There are lots of elderly Tibetans on the path. Almost all of them give me an encouraging smile. Some mime playing the violin. When one of them finally asks me to play, I simply have to start. I feel drained. No Bach this time. Finnish classics, popular songs. Then some film themes. Modern Times, The Sound of Music and such like. I only play whenever I see people walking towards me along the path. Gradually I start to feel better.

After a while, my Canadian music-lover friend appears and says he has been looking for me all over. I’ve promised to play somewhere that afternoon. I play the Preludes from the First, Fourth and Sixth Suites. He says he prefers them played on the viola as opposed to on the cello. My emotional barometer rises immediately. I ask if I can have that comment that in writing.

I then play the Chaconne, which my listener doesn’t know. Before beginning, I encourage him to sit down in a comfortable position; the piece lasts around fifteen minutes. Once I have finished, he says: ‘It couldn’t have been that long. You only just started.’

After that I play Itsy Bitsy Spider to two children, who run off giggling. I’ve been playing for two hours. As I close my case, two eagles fly past, one behind the other, barely twenty metres from where I am standing. Perhaps one of them is the eagle my school friend showed me.

The sun is setting. I sit down in the bushes, by the side of a dusty path. I don’t dare go back to the village before dark. It is 5.45 in the evening. My bus leaves at seven. I start to pack up my things. In an hour, not a single person has walked past me.

I am just about to set off down the path towards the village, when the shoeshine boy appears at the bottom of the hillside with two of his friends. He walks up to me and looks at me gravely. I look back. Neither of us says a word. I dig a bundle of notes from my pocket and give them to him. The boy doesn’t look to see how much is there, but puts the money in his pocket and thanks me.

We walk back to the village together. As we part, the boy looks me in the eyes and says: ‘If you back, many small shoes.’ I look back at him and say: ‘Promise.’

Kieślowski or Kaurismäki?

My bus is leaving soon.

Translated by David Hackston

Tags: autobiography, music, photography, travel

2 comments:

13 June 2010 on 8:19 pm

I loved this story.

28 November 2014 on 5:44 pm

I enjoyed reading your diary from Dharamsala….as a very amateur violist and a visitor to Nepal. So far, my viola has not travelled with me, but I think I should change that.

Best wishes….

PW