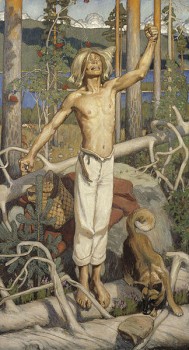

Kullervo: to be, or not?

10 September 2010 | Articles, Non-fiction

A young man is born a slave under stars that augur ill for him. He is maltreated and betrayed from birth. He cannot control his physical power, his aggression or his thirst for revenge and, finally, after fatal errors and deliberate acts of violence, his remaining desire is to die. What, in the end, did life hold for him?

The cruelly tragic story of Kullervo in the Kalevala was largely the creation of the national epic’s compiler, Elias Lönnrot (1802–1884), who put together a number of originally unconnected folk-epic fragments collected in disparate localities throughout the north and east of Finland. This process involved many stages and went on for decades. The first version was published in 1835; for a shorter version for schools in 1862 Lönnrot cut the most violent and erotic scenes – including those involving Kullervo and his sister in an incestuous encounter.

‘Kullervo emerges as the composite embodiment of at least three traditional mythological figures,’ wrote the translator and scholar David Barrett in an article, published in Books from Finland (1/1989), to accompany an extract he translated from Aleksis Kivi’s play Kullervo: ‘the wonder child of superhuman strength, the wicked magician with control over the wild beasts of the forest, the tragic hero who unknowingly commits incest (Heracles, Dionysos, Oedipus). He can also be seen as the orphan seeking revenge, the slave who refuses to be a slave and as the victim helpless against a curse brought upon his family by the sins of his fathers.’

Kivi (1834–1872) took up the subject and themes of Lönnrot’s saga of Kullervo from the newly published Kalevala; he was also inspired by Greek tragedies and (Swedish-language) translations of Shakespeare’s plays. Kivi became the first notable Finnish-language author of plays, poems and prose – and after his untimely death due to poverty, alcoholism and insanity, he was pronounced Finland’s ‘national author’.

![]() The plot of Kullervo’s story goes like this:

The plot of Kullervo’s story goes like this:

In a battle, Untamo defeats his brother Kalervo’s army. Kalervo’s son Kullervo, an unnaturally strong child, is born a slave, and Untamo sells him as a young child to Ilmarinen the blacksmith.

Ilmarinen’s wife, the Daughter of Pohjola (‘the North’) makes the boy a shepherd and bakes him a loaf with a stone inside it. Kullervo, enraged, takes his revenge by sending home a flock of bears and wolves instead of cattle, which tear her to pieces. Kullervo flees, and discovers that this parents and two sisters are alive on the border of Lapland.

He finds them, but one of his sisters is lost. Kullervo’s father sets him various tasks, but he fails in all of them. On his way home one day he finds a girl in the forest whom he abducts in his sledge and seduces. It turns out the girl is his lost sister, who then drowns herself.

Kullervo sets out to take revenge on Untamo, killing him and destroying his property. On returning home, he finds his house empty and deserted, goes into the forest and falls upon his sword.

Kullervo, Kalervo’s son snatched up the sharp sword looks at it, turns it over asks it, questions it; he asked his sword what it liked: did it have a mind to eat guilty flesh to drink blood that was to blame?

‘To be, or not to be…’ Unlike Hamlet, Kullervo chooses the latter option.

(Extract from the translation of the Kalevala by Keith Bosley, Oxford University Press, 1989.)

No comments for this entry yet