Blowing in the wind

26 November 2010 | Reviews

Clarinettist who travelled: Bernhard Crusell

Bernhard Crusell: Keski-Euroopan matkapäiväkirjat 1803–1822

[Bernhard Crusell: Travel Diaries from Central Europe, 1803–1822]

Suom. ja toim. [Translated into Finnish and edited by] Janne Koskinen

Helsinki: Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura [Finnish Literature Society], 271 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-090-5

€28, hardback

Born the son of a poor bookbinder on the west coast of Finland, Bernhard Crusell (1775–1838) had talents as a clarinettist and composer that brought him considerable fame, both in his native country and further afield. Hannu Marttila reads the diaries he wrote on his travels in Europe, where his meetings with the great and the good chart the emergence of the new Romantic sensibility

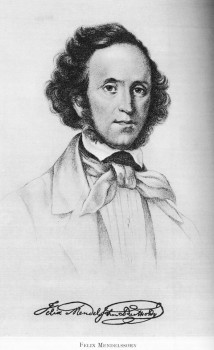

‘Felix is a most beautiful child, and he is also said to be very unassuming. In his compositions one immediately recognises the signs of genius and good training. He continues to study under Zelter, and, thanks to an anticipated large inheritance, he, too, may become an independent composer. People here think he may even become another Mozart.’

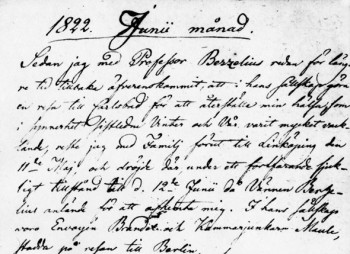

On the morning of 30 June 1822 Bernhard Crusell was invited to a home concert at the house of banker Abraham Mendelssohn. That summer the Berlin music scene offered its best; performing at the concert were the banker’s 13-year-old son Felix and his older sister Fanny.

In his travel diary Crusell, a Finnish-born clarinet virtuoso and composer, relates that Felix had already composed operas, more than 60 fugues, seven symphonies – the newest, a symphony in D minor currently under rehearsal – as well as piano pieces.

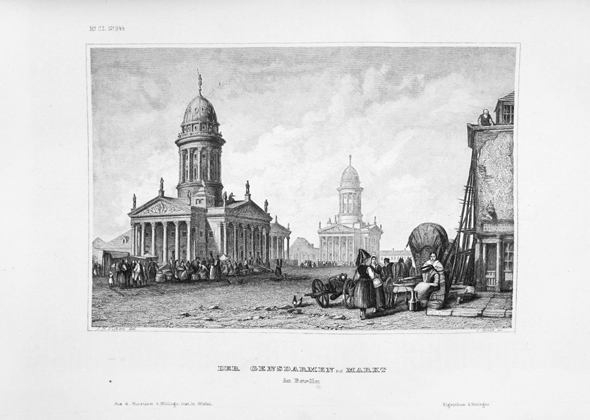

Two days earlier Crusell had heard the new opera hit, Der Freischütz (‘The freeshooter’), in the new Schauspielhaus. ‘Carl Maria von Weber’s music, an awful work, especially the second act in which the music is original but somehow rhapsodic – the second act is dreadful, shouting in place of music.’ The heat and the nerve-wracking music stole sleep from Crusell, who was fighting sickness at the time. But when the two composers met alone together in Dresden in early July, their respect was mutual, and their discussion of stage music was valuable to Crusell, who was planning his own opera, The Little Slave Girl.

The travel diaries of Bernhard Henrik Crusell (1775–1838), Finland’s first composer of international renown, have only now appeared in Finnish. The Finnish translation is based on the Swedish-language diaries edited by Fabian Dahlström in 1977. These were published by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music, to which Crusell was awarded membership when he was only 26 years old. He does belong incontrovertibly to both Finnish and Swedish music history and its living tradition. Crusell’s three clarinet concertos and three clarinet quartets belong to the core clarinet repertoire today, just as they did during the composer’s lifetime.

Particularly during his two trips to Germany, in 1811 and 1822, Crusell formed relationships with important publishers and future performers of his works. His observations of Prussia in 1811, subjugated as it was by Napoleon, were sad: the country was impoverished and humbled, and Crusell’s old clarinettist friend, to whom he had entrusted money to order a new instrument, had needed to use the money to survive.

Eleven years later, however, the culture, towns and countryside flourished anew, and the literary-minded Crusell describes them in the Romantic spirit. But now his own health is faltering, and instead of hearing about the wonders of the spa towns, we read more and more about episodes of ill health which the mineral waters appear only to aggravate.

Space for music in Berlin: the Konzerthaus (built 1818–1821) and the two churches of the Gendarmenmarkt, Französischer Dom and Deutscher Dom (Meyers Konversations-Lexikon 5, 1893–1901).

Although Crusell does not generally mention his own success in his diaries, the names of his travel companions and those he visited nevertheless make clear what sort of reputation he enjoyed as composer and virtuoso of his instrument.

Crusell’s beginnings did not portend high society circles or royal patronage. His father was a bookbinder of meagre means in Uusikaupunki (Nystad) on the west coast of Finland, who later moved to Nurmijärvi, near Helsinki: there Bernhard learned to play the clarinet from a neighbour who was a regimental musician. At the age of 12 Crusell was sent to the Sveaborg military band. Sveaborg [Suomenlinna], an island fortress off the Helsinki coast, was a true cultural centre, and there the unschooled country boy received a good general education from soirees, concerts and conversations. Bernhard taught himself French and, a few years later in Stockholm, German and Italian. His travel diaries bear witness to his ease and expressiveness in French and German. Crusell later translated opera librettos from Italian.

In the eighteenth century it began to be easier for musicians and artists to surmount class barriers than for other people. There were of course those who, like the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, kicked their Mozart out of the servants’ door when crossed, but there were also those who presaged the coming Romantic period, nobles who respected musicians as friends. Only rarely does Crusell remark after some visit that the mood was ‘icy’. The reader is left to wonder whether the reason for the chill was class pride.

Some aspects of hierarchy did remain: when the court musician Crusell, on his Paris trip in 1803, wished to stay there for another year, Sweden’s King Gustav IV ordered him to return, cloaking the command in respectful phrasing: ‘It is important to get you home to Stockholm for the winter.’

The composer's instrument: Crusell gave this clarinet, by Heinrich Grenser, to Lieutenant von Heland in the 1820s. It now is in the Music Museum of Stockholm.

And while Crusell’s noble travel companions continued their visits, expeditions and purchases, their musician friend withdrew to his quarters and turned to his role of craftsman: ‘afternoon practices’, ‘preparing reed mouthpieces’. Perhaps it was on just such an afternoon that ‘an invitation to Madame Récamier’s arrived, but I declined’. Juliette Récamier’s salon was at that time the most important in Parisian cultural circles. Several days later Mme Récamier came to hear Crusell play Mozart’s trio, ‘which went poorly due to the violist’s non-stop blunders’.

During Napoleon’s time as First Consul in Paris, Crusell visited the sights in this world city and made short, often pithy notes in two notebooks – occasionally even in Finnish, when it was a question of confidential conversations about a potential post or staying in Paris. He attended a court session and saw the guillotine, Bonaparte drilling his troops, as well as an elephant – ‘the most astonishing of all the animals’. He hears unusual music on the Champs Elysées: ‘a Negro is blowing into a galoubet while beating a drum’.

In Paris Crusell reinforces his composition studies. He finds the new music instruction both significant and interesting: the Paris Conservatory and its annual student competitions.

Perhaps most surprising in Crusell’s travel diaries is his fascination with two Paris educational institutions, the schools for the blind and the deaf, and their revolutionary teaching methods: the blind ‘see’ to read, and the deaf communicate among themselves by signing.

The results would surely have amazed anyone, yet one cannot but wonder whether Crusell’s genuine excitement resulted in part from his own journey from a poor country boy to a self-educated celebrity and man of the world for whom ‘enlightenment’ was not an empty term.

Translated by Jill G. Timbers

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jkmqZhjzRF0&feature=related

Crusell’s native town Uusikaupunki organises an annual music festival dedicated to woodwind instruments. Here, more information on the composer.

No comments for this entry yet