Northern exposure

21 June 2012 | Reviews

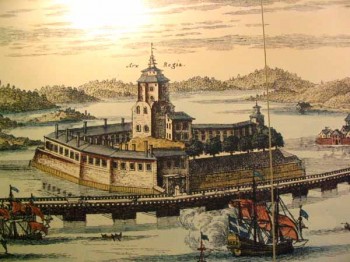

Between Helsinki and St Petersburg: Vyborg. Illustration of Vyborg Castle by an unknown artist, 1709, Wikimedia

Tony Lurcock

‘Not So Barren or Uncultivated’. British travellers in Finland 1760–1830

London: CB Editions, 2010. 230 p.

ISBN 9-780956-107398

£10.00, paperback

Finland is not unique in raising scholars who have often attempted to treat historical travellers’ accounts as source material for historical facts, and then prove how ‘wrong’ they are in relation to reality. This is an unproductive way in which to read them: travel books are nearly always based on the authors’ own country and experiences projected on what they encounter abroad.

Paradoxically, much of what was written about foreign countries in the past was really about conditions and problems in the author’s own land, and can be understood only against that background – something that also emerges in this book about British travellers in Finland.

They saw in the Nordic countries either a utopia, with free, strong and ‘natural’ people in an ordered society, or a dystopia, with rough, primitive tribes, undeveloped social conditions, a veritable lowlife Barbaria. The encounter with a ‘different’ Europe and its natives may have been trying, but it was part of the eighteenth century’s way of studying alternative worlds and world views, from Lapland to Tahiti or China.

Tony Lurcock is a former associate professor of English at the University of Helsinki and Åbo Akademi, and therefore has a good first-hand knowledge of today’s Finland to juxtapose with the manner in which his countrymen experienced the lands and people of the northern corner of Europe more than two hundred years ago. Not So Barren or Uncultivated is at once both an anthology of extracts from British travel accounts and a rich mini-encyclopaedia of personalities, routes and destinations, with references to the historical and literary background of the time.

The book presents twenty travel accounts written by authors who range from Joseph Marshall (published in 1772) to Charlotte Disbrowe, the first female traveller (whose notes, written in the 1820s, were published in 1878). They include well-known authors like Sir Nathaniel William Wraxall, who completed a journey from Stockholm to St Petersburg in 1775, William Coxe, who in 1779 set out in the opposite direction, and Edward Daniel Clarke, who, with interests of an explicitly scientific nature, travelled first in Lapland, Sweden, Norway and Finland, and then to St Petersburg, for a total of three and a half years.

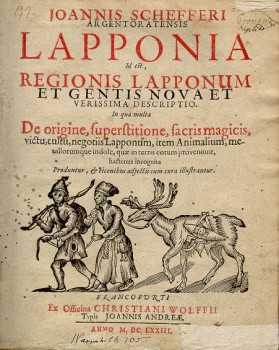

Reindeer folk: the cover of Lapponia by Johannes Schefferus, 1673. Illustration: Wikimedia

‘Unpolished in their manners, and still retaining the vestiges of Gothic ignorance, they present not many charms to tempt the traveller,’ observed Sir Nathaniel. ‘Yet, Finland is not so unfertile or uncultivated a province, as I had been taught to expect’, he admitted. However, in his opinion, ‘the peasants speak a barbarous jargon, equally unintelligible to a Swede or a Russian….’ ‘The manners of the people were so revolting,’ wrote Clarke, ‘one hesitates in giving the description of anything so disgusting.’

The foreign, usually university-educated author-travellers often had preconceived notions about Scandinavia and Finland, and until the nineteenth century and the period dealt with by Lurcock’s book these possessed many classical features. They had their origins as far back as Tacitus’ Germania (AD 98) and the ancient conception of Greeks and Romans versus ‘barbarians’ – wild forest people outside the boundaries of the known world. ‘The Fenni live in a state of amazing savageness and squalid poverty. They are destitute of arms, horses and settled abodes: their food is herbs; their cloathing, skins; their bed, the ground.’

But Clarke also found the little northern town of Torneå (in Finnish, Tornio) ‘less barbarous’: ‘The inn, a very good one for this part of the world, was clean and comfortable; and, in proof of it, we had no necessity to make use of our own sheets for the beds, which is not often the case…. The dinner…. consisted of pickled salmon, chocolate milk, by way of soup, pancakes, a kind of cakes called diet-bread, rye biscuit, and reindeer cheese. ’

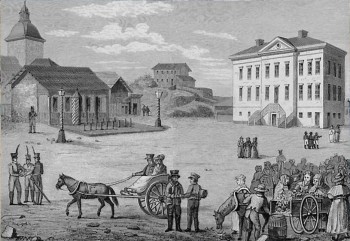

Pre-Engelian era: City Hall Square in 1920, before the rebuilding of Central Helsinki. Drawing by C.L. Engel. Helsinki University Library/Wikimedia

In 1822, to naval captain George Matthew Jones, Helsinki had ‘assumed a very imposing appearance, from the number of government buildings which are in progress, and are mostly constructed of brick stuccoed white. The senate-house is of great extent, with a staircase which does honour to the architect, Mr. Engel, a Prussian. He has been employed seven years, upon designs for improving and embellishing the town; he had the goodness to show us some of the plans, “Approuvé par l’ordre supérieur de S.M. l’empereur, le prince Volskonsk”.’

A novel feature of Lurcock’s book is his following up of the adventures and writings of British travellers in the Grand Duchy of Finland after 1809, when Finland was ceded to Russia from Sweden. British travel writing about Finland was usually part of a larger travel geography that covered the whole of the Baltic Sea region, Lapland or Russia. The books often appeared in many editions, indicating that in Britain there was a strong interest in this then relatively unknown part of Europe.

The travel accounts display many themes that also recur in the writings of continental European travellers in Finland at the time: the wild nature with its granite mountains and endless expanses of rocks, the primitive people who were regarded as natives of a remote part of the world, the poor roads, the dirt and vermin at the inns, but also the signs of civilisation and beauty. These latter included the professors at the Royal Academy of Turku, as well as Finland’s nascent urban culture and its unspoiled nature.

A special chapter in the experiences of these foreign observers was invariably provided by the northern winter with its snow and ice, and the adventures during the sea crossing from the Swedish coast via Åland and the archipelago to Turku and the Finnish mainland. There were two main travel routes, with Stockholm or St Petersburg as the starting point. One went north, towards the midnight sun and Lapland, first up along the coast of what is now the Swedish side of the Gulf of Bothnia, and then back down south via Ostrobothnia to Turku in Finland. The second went eastwards from Stockholm via Åland and Turku along the coast road on the Gulf of Finland, via Helsinki to Vyborg and to St Petersburg, just 440 kilometres from Helsinki. From 1743 to 1809 the Swedish-Russian border was situated on the river Kymmene, some 120 kilometres from Helsinki.

Business as usual: a sledge on an ice floe. A woodcut from History of the Nordic Peoples (Book 1, ch. 27). Picture: www.avrosys.nu

Olaus Magnus’ History of the Nordic Peoples, from 1555, had been published in numerous editions in many languages, and Johannes Schefferus’ classic Lapponia, first published in 1673, was for centuries the most widely distributed work about the Nordic countries on the continent. Their narrative, sometimes freely-improvised texts and evocative images created expectations for journeys to the extreme north, including Finland. Scandinavia was also an alternative for those who in the late 18th century had already ‘seen it all’, i.e. completed the usual educational grand tour of France and classical Italy.

Modern travel research is particularly concerned with the problem of the encounter with the ‘other’ in different cultures, and many of the narrative examples in Not So Barren or Uncultivated illustrate this in terms that are both drastic and entertaining.

Translated by David McDuff

Tags: Finnish history, history, travel

No comments for this entry yet