On the road, in the world

21 March 2013 | Reviews

In Romani dress: Finnish Romani women still wear their traditional velvet skirts (which weigh 5-8 kilos). Photo: Topi Ikäläinen, 1983

Suomen romanien historia

[A history of Finland’s Romani people]

Toimittanut [Edited by] Panu Pulma

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (the Finnish Literature Society), 494 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-364-7

€57, hardback

The Romani people set out from India around a thousand years ago; there are those who even claim that they originated in Egypt long before that. This latter account was favoured among the Romani in Europe, and so their leaders took to styling themselves the Dukes of ‘Egypt Minor’ or ‘Little Egypt’.

The Romani of Europe are generally considered to have come from northern India in the 15th century. They arrived in Finland – which at that time was part of Sweden – in 1512.

Five hundred years later, it seems a fitting time to publish Suomen romanien historia, a volume edited by Panu Pulma, PhD, a university lecturer in Finnish and Nordic history, with chapters contributed by a total of 14 additional experts.

The Romani who reached Stockholm, also in 1512, were said to be from ‘Egypt Minor’. This purported connection with Egypt is the origin behind the English word gypsy. The Swedish word zigenare (related to the German Zigeuner) did not come into use until the 17th century.

In Finnish, Romani people have also been called mustalaiset (etymologically related to the Finnish word for ‘black’), which carries a negative connotation. More recently it has been deemed advisable to use the word romani as a neutral term in Finnish. Suomen romanien historia is thought to be the first history of the Romani people in one country. It is no accident that it was written in Finland, whose policies concerning the Romani are considered to be among the most advanced in the world. Those policies have even been exported. For example, when I met Gruia Bumbu – then the president of the National Agency for Roma, a senior civil servant and himself a Roma – in Bucharest in 2008, he told me that Romania had used Finland’s Romani policy as its template.

When we look towards Europe now, though, the results still appear thin on the ground. One just has to pop out into the wintry cold and stroll along to any Helsinki street corner where Romani from Romania sit and beg. They have fled the poor housing, job prospects and educational, health and social policies in their own country – and therefore its unsuccessful Romani policy and downright oppression.

There has also been a great deal of iniquity in the majority population’s relationship to the Romani in Finland as well, but things have been moving in a more favourable direction. Romani people no longer die of exposure, hunger or violence as they do elsewhere in Europe. Finnish-born beggars have not been seen for decades. Discrimination was outlawed in Finland in 1972. That legislation was drafted and debated in the same years when various citizenship movements and demands for equality among people were gaining momentum elsewhere in Europe and throughout the Western world.

It is no longer permissible to speak disparagingly of the Romani in Finland in the manner of a 1573 quote from Archbishop Laurentius Petri in Suomen romanien historia, where he questioned the Egyptian origins and morals of these ‘Tatars’: ‘They claim to come from Egypt Minor, which is nothing but a lie, as they have never been to Egypt. Most of them are Scots, Jutes, Norsemen and even Swedes who have joined their numbers so that they may exercise such accursed arbitrariness.’

Or rather, such disparaging speech is not recommended or permitted according to the law, but it is still heard nonetheless. One sign of the success of Finnish Romani policy may, however, be the fact that some of the authors of chapters in Suomen romanien historia are Romani themselves. Some of them are members of prominent Romani clans, authors, artists, citizen activists, and so on. The expert authors also include researchers with Roma backgrounds, so we are granted access to Romani culture from the inside. This book contains photographs from family albums and anecdotes passed down orally about ancestors’ lives. The fact that Romani have granted their approval for this project and have been included themselves is one of the merits of this volume. This approval granted from within the culture has lent Suomen romanien historia an intimate quality that would have been impossible to achieve otherwise.

Romani mission: girls of the Sortavala town orphanage. Photo 1911

The sheer number and heterogeneity of the authors most certainly has had an impact on the scope of the subject matter covered as well as the disjointed, overlapping nature of this nearly 500-page volume, which becomes evident when one reads the book in one stretch. But Suomen romanien historia is not intended to be read as a novel with a linear plot.

The book contains a wealth of photographic material. We see poverty-stricken folk in carts, as was traditional practice in photographs of Romani, who were known in their role as horse traders. A revealing sign of the times from recent decades is shown in a photograph taken by Eeva Rista of an ordinary Helsinki streetscape in 1970, in which a Romani family stand in an urban square with an old Mercedes – in the background is an advertising pillar with a picture of a cartoon black boy with earrings advertising licorice sweets. That figure was later banished from Finland on the grounds that it was racist, along with other caricatures that were also regarded as referring to particular racial groups.

Finland underwent a transformation known as the Great Migration from the countryside to the cities in the period from the 1950s to the 1970s. That change also transformed the Romani people’s domestic culture and attitudes towards earning a living; the breeding and trading of horses was replaced by selling cars. Rural handicrafts and agricultural work were replaced by factory work – or unemployment. In the 1960s and ’70s the dearth of housing and jobs led a great many Finns, as well as Romani, to leave Finland in favour of a higher standard of living in Sweden.

Romani culture is covered comprehensively from various perspectives in Suomen romanien historia. It includes the history of Romani music, the Romani language, costume and customs, as well as stories of intergenerational relations, typical Romani occupations, beliefs and faith. There are also stories of harsh human fates. One example from the 18th century: it was common for Romani discovered without papers outside their own parish to be put into jail, sentenced to hard labour or thrown out of the country. One of the grimmest forced-labour facilities was located in the island fortress of Sveaborg in Helsinki, now known as Suomenlinna. When nine Romani were sent to Sveaborg for vagrancy in 1788 and sentenced to work, by the following year eight of them had died.

The greatest tension in Suomen romanien historia, that between the Romani and the majority population, covers the entire period from 1512 to the present day. Even the authors confirm that the Romani are seldom written about other than in the records of the district courts, so it has been impossible to avoid emphasising conflicts completely in this historical account. The press have not been any help in this regard either, with their coverage intended to be aggressive and stigmatising.

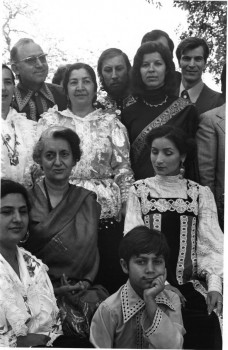

The first Romani world congress: India, 1976. The Finnish delegation visited Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (second row, left). Next to her is singer and performer of Romani music Anneli Sari who later settled in Paris. Photo: Gunni Nordström

If the historical research for this book suffers from a dearth of material, the contemporary writing is plagued by a surfeit. The sections of this book dealing with the 16th to 19th centuries outline some of the main principles, whereas the reader of the flood of 20th century socio-political reforms, faith-based Romani broadcasts, Romani associations, missions and political crises as well as proclamations and agreements will suffocate under the sheer quantity of details.

There are some real delights here and there, too. Some have considered whether a young Urho Kekkonen – who went on to become Finland’s longest serving president from 1956 to 1982 – might have taken part in massacres of the Red Guard in the Finnish Civil War. One thing that was new to me at least was that he was strongly in favour of projects to set up concentration camps for the Romani in the Finnish regions during the war years in the 1940s.

Kekkonen, brimming with energy as the director of a care centre for displaced persons, wrote a column for the Suomen Kuvalehti magazine under the pseudonym ‘Pekka Peitsi’ in which he maintained that the Romani were a work-shy, shiftlessly vagabond bunch who ‘form[ed] a grating discordance in the harmony of work and endeavour that abounds in our land’. That is quite a prejudiced model, and some thanks to the Romani who fought in the war against the Soviet Union.

According to census counts, there are around 10 million Romani in Europe. Some 10,000 live in Finland, a nation with a total population of 5.5 million. The minority holds up a mirror to the majority society: the way the majority relate to groups like the Romani reveals the values of the mainstream society.

Suomen romanien historia is a more important book than we even realise. It tells of the successful collaboration between a majority and minority population. The history of Finland’s Romani is the history of Finland itself.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Tags: ethnology, Finnish history, Finnish society, roma

No comments for this entry yet