Forest and fell

8 May 2013 | Reviews

From North to South: young Heikki Soriola on his way to represent Utsjoki in Helsinki, in 1912. Photo from Saamelaiset suomalaiset

Veli-Pekka Lehtola

Saamelaiset suomalaiset: Kohtaamisia 1896–1953

[Sámi, Finns: encounters 1896–1953]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. 528 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-331-9

€53, hardback

Leena Valkeapää

Luonnossa: Vuoropuhelua Nils-Aslak Valkeapään tuotannon kanssa

[In nature, a dialogue with the works of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2011. 288 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5870-54-1

€40, hardback

The study of the Sámi people, like that of other indigenous peoples, has become considerably more diverse and deeper over recent decades. Where non-Sámi scholars, officials and clergymen once examined the Sámi according to the needs and values of the holders of power, contemporary scholarship starts out from dialogue, from an attempt to understand the interactions between different groups.

There are around 7,000 Finnish Sámi: the northern Sámi, the Inari Sámi and the Skolt Sámi. In Sámi research and in speaking of the Sámi, however, it is often rather artificial to follow national boundaries, for the indigenous peoples of Russia, Sweden and Norway have found themselves dealing with the same kinds of fates and and assimilation policies in each country. The status of the Sámi was written into the Finnish constitution as late as 1995. There are estimated to be a total of some 100,000 Sámi, and they are the only indigenous people in the European Union.

Kivijärvi, 2011. Photo: Leena Valkeapää

These books, by Veli-Pekka Lehtola, professor of Sámi culture at the Giellagas Institute in the University of Oulu, and the artist Leena Valkeapää, both employ a flexible and multi-pronged approach in which, in addition to the colonial legacy, the strategies of the local population, its own world-view and its dynamic collaboration with society at large are all explored. Earlier Sámi scholarship has too often been marred by either colonialist thinking or a victim mentality.

Lehtola’s Saamelaiset suomalaiset is an extensive overview of the relations between the Sámi and the rest of Finland over a period of almost fifty years. The work is already a classic in its field on account of its point of view and richness of detail; it combines micro- and macrohistory, and the features on important Sámi effectively lighten the content of this massive package of information. The illustrations, most of them previously unpublished, form their own story, which supports that told in the text. The names of all the Sámi who appear in the 1930s photograph on the front cover, for example, are known, while the man standing next to the Sámi paterfamilias was, according to the person who identified the people in the picture, ’some unknown Finn’. The contrast with the habit of earlier Sámi scholarship of objectifying the minority it studied could not be stronger!

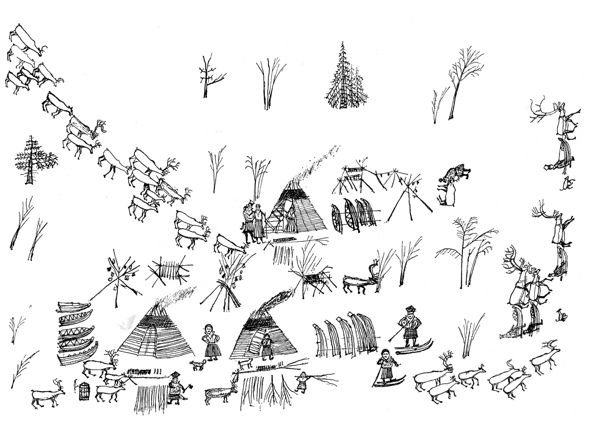

Life in Lapland: drawing by Johan Turi (1854–1936). Picture from Luonnossa

Among the book’s delicious starting points, indeed, is the depcition of the origins, level of education and prejudices of each group. When the schools inspector Onni Rauhamaa, in the 1920s, asked his young Sámi driver whether the things in the sky were northern lights, the boy replied patiently, ’Well, when the sky flashes, that’s the northern lights, those little white dots are stars, and the big round thing at the back is the moon!’

Relations between decision-makers and the Sámi are, according to Lehtola, considerably more complex than has previously been understood. For example, before the Second World War numerous ’cultural interpreters’, or Sámi, worked as advisers to Finns supporting Sámi rights. These had a great influence on the projects for the protection of Sámi culture championed by these officials or friends of Lapland. Among the most interesting historical finds is a project for the foundation of a very autonomous region in the municipality of Utsjoki, where the local council did not want new Finnish settlement, a telephone network, roads or Finnish primary schools. The proposal reached the Finnish parliament, where it was met with shocked rejection.

Leena Valkeapää’s doctoral thesis for the Aalto University, Luonnossa: Vuoropuhelua Nils-Aslak Valkeapään tuotannon kanssa (’In nature: dialogues with the work of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää’), for its part, opens up new research strategies by combining the roles of artist and scholar. Valkeapää is a Finnish artist who moved, after marriage, to life in the reindeer-herding lands of Lapland.

New life in the fells: Oula Valkeapää with a young reindeer (May, 2005)

As her sources she uses, in addition to the literary work of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (1943–2001) and the Swedish Sámi Johan Turi (1854–1936), the observations of her own husband Oula Valkeapää concerning the Sámi and their interpretation – text messages sent from his ’working environment’, the fells, among the reindeer.

The importance of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, or Áillohas, for Sámi culture can hardly be over-estimated; as a poet, joik-singer, musician and artist he became a unique and internationally respected interpreter of Sámi culture. The central dialogue is carried out between the scholar and three Sámi who lived in the reindeer-herding, nomadic culture. This auto- ethnographical approach nevertheless explores the culture from starting points determined by the scholar.

Both works unravel old stereotypes about Sámi culture, but they also challenge established conceptions about the inevitable opposition of Sámi and mainstream culture. Despite their extensive material, the works are surprisingly approachable, although it would hardly be possible to digest them at one sitting. It could be said that with Lehtola’s and Valkeapää’s research questions and methods, Sámi studies have taken a considerable step forwards.

Oula Valkeapää opened up to the scholar, in her own words, the world of ‘wind, reindeer, time, fire and man’ – existential concepts whose understanding was not self-evident to a Finn who had moved from the south. Although Sámi culture is defined through language, handicrafts and joik singing, it is the relationship with nature that is considered the unifying factor for all Sámi. Indeed, Leena Valkeapää notes that the reindeer-herding Sámi have not attempted to control or shape nature, because from the point of view of their way of life the world is complete; the art of living lies in recognising time and conditions so that the balance of nature, and life, can continue.

The nomadic lifestyle, but also the basic existential questions of human life, are movingly described in perhaps Nils-Aslak Valkeapää’s best known lines: ’My home is in my heart / and it travels with me.’

Wind, reindeer, time: Naamakkavuoma, 2010. Photo: Leena Valkeapää

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: art, ethnology, Finnish history, Finnish nature, Sámi, Sámi studies

No comments for this entry yet