Archive for December, 2013

The last Christmas tree

19 December 2013 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Reikä (‘The hole’, Like, 2013)

A four-litre saucepan should last the whole holiday, Honkkila calculates, throwing a bay leaf into the borscht.

Borscht is excellent at Christmas, as it blends the traditional Finnish dishes – beetroot salad, baked roots, ham.

At the same time Honkkila remembers the tree. He’s always had a tree, for forty years. When he was a child his dad brought it in from the back forest. Since then Honkkila has fetched his tree from various places, from the market and last Christmas from the shopping centre parking lot, but for this Christmas he has no tree.

Honkkila looks at the clock. The shopping centre is open for another hour. Honkkila takes the soup off the hob and goes out.

The shopping centre loudspeakers are beeping out electronic Christmas tunes; there are patches of spruce needles on the empty parking lot.

‘Is there anything left?’ Honkkila asks the assistant. More…

November favourites: what Finland read

19 December 2013 | In the news

Best-selling: ‘Singing songbook’, edited by Soili Perkiö

The November list of best-selling fiction and non-fiction, compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association (lists in Finnish only) features thrillers, new Finnish fiction and biographies.

Number one of the Finnish fiction list was the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Omertan liitto (‘The Omerta union’, WSOY). It was followed by the latest novels by Tuomas Kyrö, Kunkku (‘The king’, Siltala), and Kari Hotakainen, Luonnon laki (‘The law of nature’).

The translated fiction list consisted of best-selling crime writers: Dan Brown, Liza Marklund, Jo Nesbø. The Nobel Prize-winning author Alice Munro was number seven – and one of her books was at the top of the paperback fiction list.

Singing has inspired book-buyers so much that Soiva laulukirja (‘Singing songbook’, Tammi), edited by Soili Perkiö, was number one on the list of the books for children and young people: the push of a button delivers piano accompaniment to any of 50 Finnish songs – a clever idea. Perhaps it is popular with parents as entertainment for their kids on long car journeys?

The non-fiction list featured biographies of Jorma Ollila of Nokia fame, the banking tycoon Björn Wahlroos, Lauri Törni aka Larry Thorn who fought in three armies – those of Finland, Nazi Germany, and the US (he died in Vietnam in 1965) – an ice-hockey boss, Juhani Tamminen, and the sprinter Usain Bolt.

Tuomas Kyrö: Kunkku [The king]

19 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kunkku

Kunkku

[The king]

Helsinki: Siltala 2013. 549 pp.

ISBN 975-952-234-173-0

€29.90, hardback

This novel is a satirical alternative history of successful Finland and self-destructive Sweden. It is also the story of the king of Finland – the protagonist, Kalle XIV Penttinen, is driven by his instincts, which causes him to fail as a family man. Pena, as he is called, would like to play tennis all day long and watch pole dancing at night. Finland is a fantastic wonderland of film and music industry, tennis, space technology and innovative legal usage, whereas Sweden, ravaged by war, suffers from the trauma that passes from one generation to the next. Estonia has done well for a long time, and the Soviet Union (sic) is a stronghold of democracy. Chuckling, Kyrö turns history upside down. As a writer of short prose and tragicomic novels he is currently a very popular author. However, this time his typically witty associations and inventive comedy suffer from the sheer size of this novel.

Leena Parkkinen: Galtbystä länteen [West from Galtby]

19 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Galtbystä länteen

Galtbystä länteen

[West from Galtby]

Helsinki: Teos, 2013. 339 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-510-7

€32.90, hardback

Leena Parkkinen’s first novel, Sinun jälkeesi, Max (‘After you, Max’) was awarded the Helsingin Sanomat literature prize for best first work of 2009. Her new novel contains crime story ingredients, but the focus is on love between siblings, loss and the demand for truth. The story begins in 1947, after the war, on an island in the south-western Finnish archipelago. Sebastian, brother of Karen, has returned from the front; it’s time to mend the best clothes and dancing shoes. But to the horror of the island community, the body of a young girl is found on the shore, and Sebastian gets the blame. Sixty-five years later her brother’s fate has not left Karen alone, and she sets out to find the truth. Capable of handling different times, Parkkinen (born 1979) is also a skilful interpreter of conflicting sentiments, as unexpected twists develop towards the end.

Not so weird?

12 December 2013 | Non-fiction, Reviews

Johanna Sinisalo. Photo: Katja Lösönen

Johanna Sinisalo’s new novel Auringon ydin (‘The core of the sun‘, Teos, 2013), invites readers to take part in a thought experiment: What if a few minor details in the course of history had set things on a different track?

If Finnish society were built on the same principle of sisu, or inner grit, as it is now but with an emphasis on slightly different aspects, Finland in 2017 might be a ‘eusistocracy’. This term comes from the ancient Greek and Latin roots eu (meaning ‘good’) and sistere (‘stop, stand’), and it means an extreme welfare state.

In the alternative Finland portrayed in Auringon ydin, individual freedoms have been drastically restricted in the name of the public good. Restrictions have been placed on dangerous foreign influences: no internet, no mobile phones. All mood-enhancing substances such as alcohol and nicotine have been eradicated. Only one such substance remains in the authorities’ sights: chilli, which continues to make it over the border on occasion. More…

Bring on the white light

12 December 2013 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Auringon ydin (‘The core of the sun’, Teos, 2013). Introduction by Outi Järvinen

Jare, March 2017

‘We call the chilli the Inner Fire that we try to tame, just as our forefathers tamed the Worldly Fire before it.’

Mirko pauses dramatically, and Valtteri interrupts. ‘Eusistocratic Finland offers us unique opportunities for experimentation and development. Once all those intoxicants affecting our neurochemistry and the nervous system have been eradicated from society, we will be able to conduct our experiments from a perfectly clean slate.’

‘We fully understand the need to ban alcohol and tobacco. These substances have had significant negative societal impact. And though in hedonistic societies it is claimed that drinks such as red wine can, in small amounts, promote better health, there is always the risk of slipping towards excessive use. All substances that cause states of restlessness and a loss of control over the body have been understandably outlawed, because they can cause harm not only to abusers themselves but also to innocent bystanders,’ Mirko continues.

This is nothing new to me, but I must admit that the criminalisation of chillies has always been a mystery to me. By all accounts it is extremely healthy and contains all necessary vitamins and antioxidants. A dealer that I met once told me that people in foreign countries think eating chillies can lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels – and even prevent cancer. If someone makes a pot of tom yam soup, sweats and pants over it and enjoys the rush it gives him, how is that a threat, either to society or to our health? More…

On the shortlist: Runeberg Prize 2014

12 December 2013 | In the news

On the shortlist of the Runeberg Prize 2014 are eight books. Four of them are novels: Lapset auringon alla (‘Children under the sun’, WSOY) by Miki Liukkonen, Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our daily life’, Teos) by Riikka Pelo (which was awarded the Finlandia Prize for Fiction in December), Pintanaarmuja (‘Scratches’, ntamo) by Maaria Päivinen and Terminaali (‘The terminal’, Siltala) by Hannu Raittila.

The other four books on the list are two collections of poetry, Pakopiste (‘Vanishing point’) by Kaisa Ijäs (Teos) and Öar i ett hav som strömmar by Henrika Ringbom (Schildts & Söderströms). Ahtaan paikan kammo (‘Claustrophobia’, Robustos) by Riitta S. Latvala is a collection of short stories, and Kopparbergsvägen 20 (‘Kopparbergsvägen Road 20’, Schildts & Söderströms) by Mathias Rosenlund is an autobiographical work.

The list was compiled by a jury of three: cultural editor and critic Elisabeth Nordgren, author and critic Irja Sinivaara and author Jouko Sirola.

The prize, worth €10,000, was founded by the Uusimaa newspaper, the City of Porvoo, both the Finnish and Finland-Swedish writers’ associations and the Finnish Critics’ Association. On 5 February, on the birthday of the national poet J.L. Runeberg (1804–1877), it will be awarded for the 28th time in his native town of Porvoo.

Pauliina Rauhala: Taivaslaulu [Heaven song]

12 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Taivaslaulu

Taivaslaulu

[Heaven song]

Helsinki: Gummerus, 2013. 281 pp.

ISBN 978-951-20-9128-7

€29.90, harcback

A religious revivalist movement is the framework for this skilfully written first novel. A young couple, Vilja and Aleksi, dream of a brood of children. Nine years and four children later Vilja feels that all joy and strength has drained away from her life. Living the reality of their religion’s ban on family planning, the couple is hit hard by the fact that Vilja is expecting twins. This is too much for her; she feels crushed by anxiety and fatigue. The ethical ground of parenthood, the good and bad sides of a religious community as well as the myths and expectations surrounding motherhood are Rauhala’s main themes. This impressive tale also contains a love story; Aleksi is a credible and sympathetic husband who first and foremost wants to believe in his wife and his family.

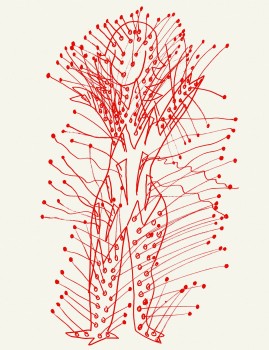

Mad men

5 December 2013 | Non-fiction, Reviews

lllustration from the cover of Hulluuden historia

Hulluuden historia

[A history of madness]

Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2013. 456 pp.

ISBN 978-952-495-293-4

€39, hardback

The Hippocratic Oath’s principle, primum non nocere – ‘first, do no harm’ – has been particularly difficult to apply in practice for doctors who have devoted themselves to sicknesses of the soul.

The breaking with this principle is the first thing to strike the reader in Professor of Science and Ideas Petteri Pietikäinen’s book, Hulluuden historia, which is overflowing with ideas.

This could be due to the vast amount of information contained within the book, combined with its slightly chaotic structure. It skips between a chronological and thematic narratives, and the author’s own involvement in his text varies, meaning that the text itself swings between vigorously discursive, and something that is little more than a sluggish retelling. Taking in everything Pietikäinen wants to say is difficult; the reader inevitably begins to grope for exciting details, and there are of course plenty of those to be found.

The sad thing is that the development of mental health care has not advanced steadily at all from its dark and ignorant beginnings towards a brighter and more enlightened present. Setbacks, especially concerning patients’ safety, have been many. Even if we ignore centuries of exorcisms, abuse, and care in the form of incarceration, punishment, and physical punishment, the 20th century has a wealth of gruesome examples to offer. More…

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2013

5 December 2013 | In the news

Riikka Pelo. Photo: Heini Lehväslaiho

The director general of the Helsinki City Theatre, Asko Sarkola, announced the winner of the 30th Finlandia Literature Prize for Fiction, chosen from a shortlist of six novels, on 2 December in Helsinki. The prize, worth €30,000, was awarded to Riikka Pelo for her novel Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday life’, Teos).

In his award speech Sarkola – and actor by training – characterised the six novels as ‘six different roles’:

‘They are united by a bold and deep understanding of individuality and humanity against the surrounding period. They are the perspectives of fictive individuals, new interpretations of the reality we imagine or suppose. Viewfinders on the present, warnings of the future.

‘Riikka Pelo‘s Jokapäiväinen elämämme is wound around two periods and places, Czechoslovakia in 1923 and the Soviet Union in 1939–41. The central characters are the poet Marina Tsvetaeva and her daughter Alya. This novel has the widest scope: from stream of consciousness to interrogations in torture chambers and the labour camps of Vorkuta; always moving, heart-stopping, irrespective of the settings.’

The five other novels were Ystäväni Rasputin (’My friend Rasputin’) by JP Koskinen, Hotel Sapiens (Teos) by Leena Krohn, Terminaali (‘The terminal’, Siltala) by Hannu Raittila, Herodes (‘Herod’, WSOY) by Asko Sahlberg and Hägring 38 (‘Mirage 38’, Schildts & Söderströms; Finnish translation, Kangastus, Otava) by Kjell Westö (see In the news for brief features).

JP Koskinen: Ystäväni Rasputin [My friend Rasputin]

5 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Ystäväni Rasputin

Ystäväni Rasputin

[My friend Rasputin]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2013. 355 pp.

ISBN 978-951-0-39772-5

€29.50, hardback

Prophet, healer, mystic – and political player and lecher. The hectic life of the Russian Rasputin, which ended in 1916 in assassination, offers excellent material for JP Koskinen’s novel. The fictive narrator is the young Vasili, who Rasputin hopes will be a follower. The mix of fear and adulation and wild events, described from the point of view of the young boy, are persuasive. At the court of Tsar Nicholas II Rasputin gained favour because the Tsarina trusted almost blindly in his healing abilities: the imperial family’s son Alexei was a haemophiliac. JP Koskinen’s earlier works include science fiction. Ystäväni Rasputin is a skilful writer’s description of historial events on the eve of the Russian revolution; it paints an interesting and intense portait of the atmosphere and events of the St Petersburg court. Koskinen does not over-explain; interpretation is left to the reader. The novel was on the Finlandia Prize shortlist.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins