Updated, alive

8 May 2014 | Non-fiction, Reviews

Minna at 50. The Finnish flag is flown on her birthday: 19 March has been named the Day of Equality. Canth also flies on the tail of one of the aircrafts of the Nordic airline Norwegian: the fleet carries portraits of ‘heroes’ and ‘heroines’ of four Nordic countries (the other Finn is the 19th-century poet J.L. Runeberg). Original photo: Viktor Barsokevich / Kuopio Museum of Cultural History

Herkkä, hellä, hehkuvainen – Minna Canth

[Sensitive, gentle, radiant – Minna Canth]

Helsinki: Otava, 2014. 429 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-23656-6

€40.20, hardback

There are two sure methods of preserving the freshness of the works of a classical author in a reading culture that is increasingly losing its vigour.

The first is to give a high profile to new interpretations of them, either in the form of scholarly lectures or of artistic re-workings, such as dramatisations, librettos or film scripts. Another unbeatable way to keep them alive as a subject of discussion is an updated biography, through which the author is seen with new eyes.

Minna Canth (1844–1897) is now celebrating her 170th anniversary, and she is fortunate in both respects. Having begun her literary career in the late nineteenth century, she still continues to be Finland’s most significant female writer.

Her influence on the role of women in society and, in particular, her promotion of girls’ education, is the cornerstone of Finland’s social equality. In the twenty-first century Canth’s plays are still receiving new interpretations, and they have also been made into operas and musicals. (Read her short story, ‘The nursemaid’, here.)

One play often performed is Anna Liisa (1895), the tragedy of a young girl who kills her newly born child. Its Dostoevskian, guilt-focused ending has remained open to interpretation to this very day. Another long-time favourite is Työmiehen vaimo (‘The workman’s wife’, 1885), a didactic play that portrays the radical urban working class and the struggle for women’s rights. The play brought about a change in the law when in 1899 women in Finland ceased to be regarded as their husbands’ property. Recent performances of it have included a version by Helsinki’s Avoimet Ovet (‘Open Doors’) company in the spring of 2014.

The vitality of her fiction lies in its modern characterisation, the centre of which is usually a girl or woman on the threshold of a new era. The principal themes of her work are class distinction, poverty that drives people to madness, repressed sexuality and double standards.

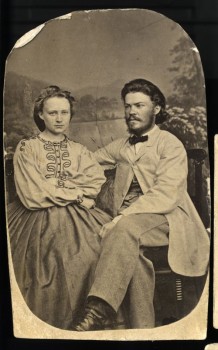

Engaged: Minna and Ferdinand in 1865. Original photo: Kuopio Museum of Cultural History

One topic of discussion in the anniversary year is Minna Maijala’s (born 1975) new biography Herkkä, hellä, hehkuvainen – Minna Canth (‘Sensitive, gentle, radiant – Minna Canth’). It is critical of the earlier biographies of Canth, especially the book by Lucina Hagman, who in the years 1901–1906 wrote the earliest extensive work on Canth’s life. It canonised an image of her that has lasted to this day, of a writer as a female victim who fought her way to the centre of literary culture.

In Hagman’s biography Minna Canth’s husband, and the father of her seven children, is demonised as a tyrant. Their marriage is portrayed as a young woman’s prison, in much the same way as Canth herself portrayed the fate of the women in her fiction, which early commentators viewed as being autobiographical.

The image of Minna Canth as a wife and mother fighting her way up from her subordinate status fitted the requirements of Lucina Hagman in her role as pioneer of the Finnish women’s movement better than it did the Minna Canth – equal, supported by men – who is documented in Maija Maijala’s book. This new study shows that in fact Ferdinand Canth provided continuous support for his wife’s work for women’s emancipation and published her earliest articles on the subject in the newspapers he edited in Kuopio, a town in north-eastern Finland, where the family lived. He also quickly made his wife his working partner in the newspaper of the Young Finnish Party [the liberal Fennomane movement].

Earlier portrayals of Minna Canth have seen her as a woman released from family hell when her husband died suddenly, after fourteen years of marriage. Not until then did the 35 year-old single mother of seven children become a controversial author who was also a successful cloth merchant, when she began to take care of her parents’ family firm.

A view from the steeple: Minna was given the key to the tower of the Kuopio Cathedral as she liked to excercise by going up and down the stairs. Her home is at bottom left. Original photo: Kuopio Museum of Cultural History

The new biography portrays Canth’s loss of her husband as a major crisis in her life. When she became a widow she was expecting her seventh child, and she became seriously ill in childbed – almost to the point of psychosis. Minna Maijala provides some interesting commentary on the attitude taken by earlier biographers to Canth’s mental collapse. According to them, she overcame her anxiety by sheer will power because she was an Amazon with fighting spirit. Maijala, on the other hand, highlights the author’s sensitive nature, and points out that she had difficulty in achieving mental balance throughout her adult life. She suffered from hypochondria, nervousness, and a variety of psychosomatic disorders.

Maijala’s book is the story of the writer behind the martyr legend, and it gives an excellent account of Minna Canth’s religious thought. She had adopted a scientific world view, and was known as a critical social thinker and polemicist. At the same time, however, she was also a professing Christian for whom the New Testament doctrine of love was the most important value. While for a naturalistic author it was a rare combination, it is also aptly illustrates the borderland between old and new that Minna Canth inhabited.

Translated by David McDuff

Tags: biography, classics, drama, Finnish history, Finnish society, literary history, writing

No comments for this entry yet