Hare-raising

13 February 2015 | Reviews

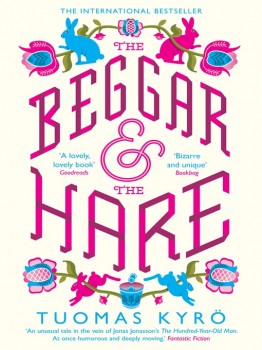

In this job, it’s a heart-lifting moment when you spot a new Finnish novel diplayed in prime position on a London bookshop table – and we’ve seen Tuomas Kyrö’s The Beggar & The Hare in not just one bookshop, but many. Popular among booksellers, then – and we’re guessing, readers – the book nevertheless seems in general to have remained beneath the radar of the critics and can therefore be termed a real word-of-mouth success. Kyrö (born 1974), a writer and cartoonist, is the author of the wildly popular Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking umbridge’) novels, about an 80-year-old curmudgeon who grumbles about practically everything. His new book – a story about a man and his rabbit, a satire of contemporary Finland – seems to found a warm welcome in Britain. Stephen Chan dissects its charm

Tuomas Kyrö: The Beggar & The Hare

Tuomas Kyrö: The Beggar & The Hare

(translated by David McDuff. London: Short Books, 2011)

Kerjäläinen ja jänis (Helsinki: Siltala, 2011)

For someone who is not Finnish, but who has had a love affair with the country – not its beauties but its idiosyncratic masochisms; its melancholia and its perpetual silences; its concocted mythologies and histories; its one great composer, Sibelius, and its one great architect, Aalto; and the fact that Sibelius’s Finlandia, written for a country of snow and frozen lakes, should become the national anthem of the doomed state of Biafra, with thousands of doomed soldiers marching to its strains under the African sun – this book and its idiots and idiocies seemed to sum up everything about a country that can be profoundly moving, and profoundly stupid.

It’s an idiot book; its closest cousin is Voltaire’s Candide (1759). But, whereas Candide was both a comedic satire and a critique of the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), The Beggar & The Hare is merely an insider’s self-satire. Someone who has not spent time in Finland would have no idea how to imagine the events of this book. Candide, too, deployed a foil for its eponymous hero, and that was Pangloss, the philosopher Leibniz himself in thin disguise. Together they traverse alien geographies and cultures, each given dimension by the other.

In The Beggar & The Hare, the foil to the Romanian hero, Vatanescu, is a Finnish rabbit. The rabbit is not a philosopher, and is not a foil. The rabbit acts as an angel of God and, essentially, carries the weight of the entire book’s lurch from misfortune to misfortune to misfortune to miracle.

But it’s a wonderful book. Mr Everyday Finn is represented superbly by fatty Pykström, who is eating and drinking himself to death in the wilds, in the forbearing company of his wife, who does Zumba and is writing a perpetual doctorate on feminist cultural studies from the beginning to the end of time.

The book is also a considerable political satire – or at least it seems to be. Not having kept up with Finnish political personalities, it is difficult to imagine Simo Pahvi [‘Cardboard’] as anything other than a crude archetype of a particularly crude form of populist Finnish politician. If it turns out the author, Tuomas Kyrö, is satirising or just plain depicting a real person, then that person should now commit suicide out of sheer embarrassment. It is hard to distinguish whether Kyrö is in love with butchering a particular politician, or just in love with butchering; but someone like Pahvi just cannot be part of a Europe in which Finland tries to be taken seriously.

But I take the book also to be a genuine, if fantastic, tale of an illegal migrant to Finland – someone who escapes the protracted asylum system and its terrifyingly ‘humane’ efforts to treat claimants fairly but strictly, but which drives them to insanity instead. Vatanescu as illegal migrant is first criminalised on CCTV by being unable to observe the bureaucratic requirements of the country where everything needs a licence. Owning a rabbit or being adopted by a rabbit is a crime. Hygiene laws abound. And, if there was anything about Finland that finally discouraged all thoughts of staying there for any decent length of time, apart from its endless winter night, its alcoholism, its utter cleanliness, the requirement to jump into freezing lakes and roll naked in snow and be whipped afterwards, the ubiquity of books depicting Moomintrolls, and the language with (by my last effort to count) 17 future conditionals, it was the paperwork that gave permission to breathe in a health and safety-assured manner.

Oh, and I live to jaywalk. I recall crossing the main street in Tampere, against the lights, with no traffic in sight for hundreds of metres in either direction – and being castigated on the other side by a citizen who said I should be ashamed for being such a lawless vagabond.

In Kyrö’s book, neither the environmental movement nor the youth of the country are spared. The sympathetic creatures are his fellow illegal migrants. It is they who bring a sense of human solidarity to an otherwise bleak book when it comes to simple human relationships.

So, is this a book of loving satire? Or one of satirical denunciation? It is a somewhat shallow and episodic book. No character develops or grows, except to a very limited extent, the arch-villain, Yegor. It is certainly one episode piled upon another, until the reader is screaming for an end to the endless accounts of one failure by Vatanescu after another. Vatanescu finally gets the football boots he has promised his son in Romania. To get them he has to become Prime Minister of Finland. He has no qualities whatsoever to become Prime Minister. He is a vacuumed soul. He has a rabbit. Finally, the rabbit deserts him because Prime Ministers must live in germ-free surroundings and a rabbit, after all, is full of diseases, lives with its diseases, and is allergic to sterility. Finns live with Finland.

Rather, Finland lives on while populated by Finns. They invented a variant of the tango where each bar ends on a downbeat. No one else could or would do this. The Finns love this tango. I think Kyrö loves Finland so, yes, let’s settle on loving satire. I smiled a lot when I read this book.

No comments for this entry yet