The universal eye

Issue 2/1985 | Archives online, Authors

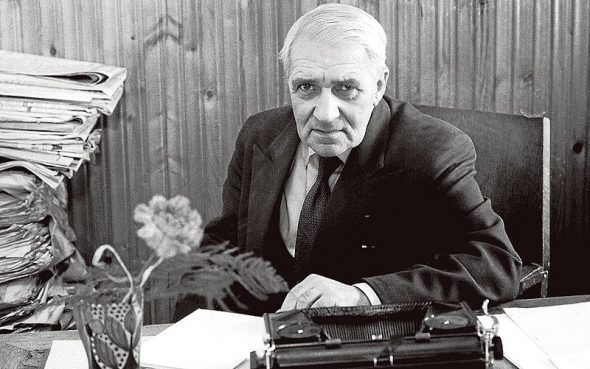

Gunnar Björling. Photo: Holger Eklund

Gunnar Björling (1887-1960) began his poetic career at the age of 35 with the collection of verse Vilande dag (‘Resting day’, 1922), which revealed the influence of romantic idealism and clearly showed its author’s preoccupation with ethical and philosophical problems of existence. Names such as those of Pascal and Spinoza, Guyau and Tagore, Dostoyevsky and Strindberg occur throughout this collection, the basis of which was formed by Björling’s study of the work of the great Finland-Swedish moral philosopher Edvard Westermarck, from whom the poet derived his concept of relativity and his philosophy of the unbounded. The dammed-up energy that can be sensed in this first volume breaks out with full force in Krosset och löftet (‘The cross and the promise’, 1925): with this, the phase of idealistic expectation comes to an end and Björling the expressionist emerges, giving utterance to ‘unbounded life’, in all its clarity and confusion, yet still within the same framework of ‘growing boundedness’: ‘We live in the concrete, and this gives our abstractions fateful wings.’

In the literary magazine Quosego (1928-29) Gunnar Björling emerged – uniquely in Scandinavia – as a dadaindividualist. Even here it was evident that his poetry was bolder, more distinctive and more uncompromising than that of any of the other Finland-Swedish modernists, and he cultivated this idiom to develop a nature poetry of great openness in Kiri-ra! (1930). Solgrönt (‘Sungreen’, 1933) takes all the leading themes of the earlier collections and sets them for full orchestra in the ‘programme’ poems Som mumlare (‘Like mumblers’), Formeln (‘The formula’) and Det oavslutades gud (‘The god of the uncompleted’), which burn with a furious revolutionary zeal, the struggle for a new language, a new world and a new, unbounded and unmediated conception of life. Of the three, Formeln is possibly the most clearly elaborated: a defence and an expression of Björling’s moral and aesthetic point of view, a hymn to the universe of living things and to the striving of an eternal will towards unattainable ideals. At its innermost level, the poem seems to concern the balance of life’s sharedness seen within a reality that is kaleidoscopic, and the supremacy of life above all theories.

It is this openness to life, this uncompromising endeavour to go one’s own way, this ability to sharpen the seeing of ‘the universal eye’ that give Björling’s poems their continuing actuality and striking force. ‘In every word light is a poem’ is a theme on which the sixteen collections that follow provide variations, and it is one which has more to do with a kind of moral keen-sightedness than with any notion of a ‘pure’ poetry: ‘pure poetry is the life of duty and temperance of thought and wild perspectives.’ For the aging Gunnar Björling the primary task becomes seeing and listening to ‘nothing but the unheard-of’ within his personal universe, and the creation of a poetry of ever broader, more open and more concrete dimensions, one in which the ‘uncompleted’ poems can be combined in new constellations, and in which they can exchange places with one another, be reconsidered and weighed one against the other.

In his poetry Gunnar Björling sought direct contact with primary sense-experiences in a language of great distinctiveness, integrity, concentration and – as has already been pointed out – openness. He wrote in his own universal language – often brief notes on nature and the role of human beings in the visible and experiential; the basis of this poetry was worked out in the great programmatic poems of Solgrönt. In Björling’s work life and poetry become one.

Translated by David McDuff

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Bo Carpelan

Solid, intangible - 26 September 2013

Autumn's child - 17 November 2011

Scent of greenness - 21 April 2011

A smell of the sea - 30 March 2000

Fruits of reading - 30 December 1998

-

About the writer

The Finland-Swedish writer Bo Carpelan (1926–2011) published his first collection of poems in 1946. He also published prose, children's books and drama; Carpelan was awarded the Finlandia Fiction Prize twice, in 1993 and in 2005, for his novels Urwind and Berg.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.