What’s so great about paper?

17 September 2009 | Articles, Non-fiction

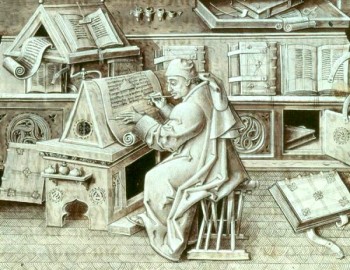

High-tech: the ultimate gadgets of the 15th century, parchment and pen. A portrait of Jean Miélot, the Burgundian author and scribe, by Jan Tavernier (ca. 1456)

The day will soon come when commuters sit on a bus or train with their noses buried in electronic reading devices instead of books or newspapers. Teemu Manninen takes a look at the digital future

Most people interested in books are aware of the arrival of electronic reading devices such as the Amazon Kindle, a kind of iPod — the immensely popular portable music listening device made by the company Apple — for electronic books. For a literary geek like me, the Kindle and e-readers should be the ultimate gadget: a whole library in a small, paperback-sized device. However, I’ve been wondering why digital reading hasn’t become as popular as digital listening. I myself have not invested in an e-reader, although I ought to be exactly the desired kind of customer. After all, I read all the time. Even the mp3 player I have is mostly used for listening to audio books.

But the Kindle, and the other e-readers around today, don’t offer everything I want from a mobile reading device. A lot of what I’d like to read is still not available on them (say, digitized 16th-century books). The screen where the text appears isn’t as nice as it could be or doesn’t have as many functions as it could. Perhaps one of the up-and-coming devices like the Plastic Logic reader, a slim device with no buttons that turns pages by touch, will change that in the near future — but then again, my problems with e-readers aren’t exactly problems which the right kind of device will solve. They’re problems with a more fundamental level of the reading experience, about everything material about reading and literary culture.

These thoughts I’ve had about mobile reading are also related to the changes that are going on in the publishing world, where traditional paper media like newspapers and magazines are struggling, and print publishers are eager to come up with new business models. I find myself wondering what the implications are for authors and what they write — for literature itself.

One option is tenacious optimism. The science fiction and fantasy author Michael Stackpole recently argued that authors must take advantage of the new content delivery methods which digital publishing is providing them with. He is the first author to publish short stories through the iPhone App Store, the online store which sells applications, or ‘apps’, for Apple’s mobile phone, the iPhone. Apps are little programs that let you do all kinds of weird and wonderful things, like find restaurants and gas stations, log gym workouts, see where your friends are on digital map displays, and so on. According to Stackpole, digital publishing offers a chance for young writers to reach audiences and create markets for their work without relying on major publishers.

Of course, Stackpole doesn’t take the problem of quality control into account. After all, the ‘job’ of most publishers is not just to deliver content but to find the best writing out there; good publishers are also reliable critics. But he does intuit, and I believe correctly, that digital publishing is already having an impact on the nature of what we read. He cites the example of the ‘commuter market’: people who read one or two chapters on their way to work or home. This kind of reading, Stackpole surmises, could point the way to a return to 19th-century publishing models, such as serial fiction (think of Dickens, whose fame and wealth was based on serialised novels which appeared in literary magazines).

It is important to note that Stackpole is not talking about the death of the novel or some utopian future where we no longer have paper books. I think the dumbest approach would be to believe that digital reading can simply copy paper reading and thereby take over its functions.

Certainly, some new electronic publishing platforms like Issuu and Scribd try to mimic paper books by having animated, turnable pages, but I don’t think this kind of digital publishing will ever replace printed books, no matter how well they mimic paper on the screen. This is simply because they are already something else, a new kind of reading experience which is arranging itself around the idea of the book, but is also being interpreted through social networking media like blogs, Facebook or Twitter, where anyone can share their thoughts with a community of readers.

When reading becomes a part of a social network (just think of Harry Potter fans), reading and writing morphs from a solitary activity to a socially shared engagement: authors connect with readers on a much more immediate basis (through comments, for instance), readers share their reading experiences, write fan fiction, and may even play-act scenes from their favorite books.

So, there are all kinds of new possibilities for reading and publishing. But at the same time we are living in a world where traditional paper forms of publishing are dying. Some media ideologists, like Richard Eoin Nash, believe that this is a good thing. Nash points out that ‘reading increasingly is writing — readers are writing back in all sorts of ways, commenting on books, re-mixing books as in fan fiction, or creating from scratch, and publishers, rather than barring this activity, or hiding from it, need to embrace it and find ways to serve it.’

In a way, though bombastically overstating the case, Nash is right. Literary communities coming together and doing things seems to be the trend for many of the numerous book-related events and happenings on the net, from a community annotating Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook online to a joint effort to ‘map’ Thomas Pynchon’s Los Angeles, to a recent technology start-up offering a service for making your own newspapers.

With such community efforts we come to my central argument — it’s not (or at least not only) the well-designed device which will make digital reading popular, but everything it’s connected to. The computer company Apple is a good example. Most people know it makes computers, but in the last ten years it has been mobile devices like the iPod and the iPhone which have made it really popular. What makes the iPod and the iPhone so great? The fact that the iPod is easily connected to iTunes, the fancy-looking online music and video store, which also helps you catalog your music in visually appealing ways.

The iPhone, for its part, was certainly a fancy phone with its touchscreen and all, but what made it a hit product was the App Store, which gave the phone thousands of new uses in everyday life. As Richard Ziade, an American web consultant, has pointed out, ‘The iPod/iTunes ecosystem is testament to the fact that people are willing to pay for a quality experience, even if there are fringe alternatives out there for free… Content is part of the experience.’

Now think about it from this point of view: what makes books so great? Libraries and book stores, and beyond them, literary magazines and newspapers and publishers and critics and book fairs and book readings and everything that makes up literary culture. A book is never just a book, a mere platform or an interface; it’s a part of a reading experience which stretches out from the immediate moment to something more universal.

So what I’m arguing is that digital reading will become a success when the devices become not only screens that let you read, but extensions of digital libraries and bookstores and whole reading communities. The Kindle, made by the online department store Amazon, is certainly a step towards the right direction. It offers a constant wireless connection to Amazon’s virtual shelves, and its growing popularity is testament to my argument.

At this point one might ask why the ailing, traditional publishing companies haven’t embraced digital reading yet. One reason could be the fact that paper publishing is still tied down by its own material nature, the literary print culture that has developed around it. They cannot envision reading as anything other than paper reading, and therefore cannot grasp that digital reading is a different kind of experience, demanding a different approach.

As the author Seth Godin has argued, ‘the new business isn’t the same as the old business, just with computers’, and Richard Ziade makes the same point when he claims that in the digital realm, ‘the physical constraints of content’ which traditional media publishers still often cling to become a ‘nuisance’ for digital users.

To reiterate, in order for digital reading to become more popular doesn’t simply entail scanning books and making them digitally available on any device that can display them. It means that one needs to build a new way to interact with and experience content. As an example, digital music publishing has done away with the idea of the traditional album. People now buy individual songs, and make their own collections or ‘play lists’ as they are called. Here, digitality simply means the ability ‘to pick and choose’ what you want to listen to in a way which traditional, material forms of music publishing made difficult.

In conclusion, I’d like to come back to the idea proposed by Michael Stackpole: that we might see a resurgence of serial fiction in the future, because digital reading makes it easier to collect such ‘play lists’. Personally I agree. I’m constantly annoyed by the fact that there are so many good stories hidden in paper magazines which I either never see or don’t want to buy because the rest of the content is rubbish. A delivery system that would allow me to download stories by authors I like would be marvellous. If a similar service were to be implemented for poetry, I would be in reading heaven.

But I’d like to believe that the digital reading revolution will go even further in inventing new ways for literature to exist in the world; most simply I’d like to believe that digital reading will make literature more available, and make people read even more. Books are, after all, cumbersome, and we are becoming more and more mobile.

Again, this does not mean, as the designer and marketing guru Russell Davies has argued, that we’re in an age where books are about to disappear (although environmentally speaking that would be a good thing!). Paper and ink will never go away, but only change in function as they become embedded in new ways of being in the world. Paper books might once more become luxury artefacts, as they used to be in the age before printing began.

Tags: ebooks, media, publishing

1 comment:

Trackbacks/Pingbacks:

-

Linkology: The Best of the Internet for 10/16/09

16 October 2009 on 5:03 pm[…] E-books come into their own when they connect a reader to everything else a favorite author has written. […]

18 September 2009 on 2:32 pm

This is a great piece. And frankly, I think we are already seeing a resurgence of serial fiction for a variety of reasons, the readers lack of attention span for one. Since I write serial fiction, I’m very excited about this trend. :)