All beauty

17 November 2011 | Authors, Reviews

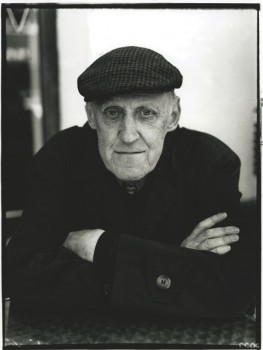

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Ulla Montan

The epigraph to Bo Carpelan’s prose work, Blad ur höstens arkiv. Tomas Skarfelts anteckningar (‘Leaves from autumn’s archive. The notes of Tomas Skarfelt’) is a quotation from Goethe: Zum Erstaunen bin ich da (‘To marvel I am here’). The world is a wonder to behold, one’s curiosity ought to be satisfied with less. It could stand as a motto for the whole of Carpelan’s literary work.

That work is now complete. Bo Carpelan died in February this year at the age of 84. He had made his debut in 1946 with the poetry collection Som en dunkel värme (‘Like an obscure warmth’).

In his prose as in his poetry, Carpelan built on a process of heightened and unconditional perception. Where others see only trees or forest, he saw a complex, branching light. His poetic ‘I’ could even watch itself perceiving, as when one autumn evening Tomas Skarfelt writes of a long-eared owl: ‘The yellow eyes looked at me attentively for a moment: a rather large, feather-clad camera.’ Carpelan often complained of having a poor memory, but it was a photographic one.

His first prose work for adults, Rösterna i den sena timmen (‘Voices in the late hour’) appeared in 1971, a quarter of a century after his emergence as a lyricist. And this year a quarter of a century has passed since his prose breakthrough with Axel (a novel depicting the life of a relative of the composer Jean Sibelius, translated into six languages, also in English). Carpelan’s native language was indeed poetry, but he extended that language with prose that bore his own personal stamp, a parlando in which the words are lined with air but honed with precision.

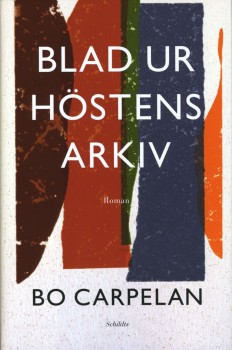

Blad ur höstens arkiv (Schildts, 2011; in Finnish, Lehtiä syksyn arkistosta, Otava) consists of 101 diary entries made by Tomas Skarfelt, a retired statistician who remains at his summer cottage even though summer has now run its course. He reflects in elegiac fashion, immersed in nature, watching his ‘I’, sometimes close to and sometimes at a distance. He is also a grumbler. The reader is probably most content when he appears as a sour old man, for then the author can make play with this. Right to the last, Carpelan was able to spin moods out of nowhere while slipping in bon mots like a cabaret performer.

The cover indicates that this is a novel. Carpelan’s work has highlighted problems of genre before. When (uniquely) he received the Finlandia Prize for the second time with his prose work Berg, the award had been narrowed to a prize for novels only, and the choice sparked a debate: was this really a novel? As a book, Berg was poetic and beautifully written, but it lacked a plot, some critics said. This time the plot consists of an ‘I’ that records its insights into the conditions for peaceful coexistence with the world while it watches the autumn closing in around it. The book is a Song of Songs of the everyday: viewed closely, each day is a miracle – ‘Strange, all beauty.’

The self and the world are not alone with each other. In its two hundred pages, Blad från höstens arkiv contains, I believe, more varied elective affinities than any other work by Carpelan. Joyce, Pavese, Emerson, Kierkegaard, Buber, Hesse, Kafka, and all the others: they are there as conversation partners, exact quotations, or semi-furtive nods of greeting. The most assiduous guest is Odradek, an incomprehensible and indestructible ‘something’ which Carpelan has borrowed from a short story by Kafka and now, with a collegial gesture, makes his own. Odradek becomes the name of Tomas Skarfelt’s unease, which follows him through the autumn.

Cover: Anders Carpelan (graphic designer, Bo Carpelan's son)

Bo Carpelan’s posthumous prose derives its intense vitality from the fact that in it the personal is given a precision that cranks it up into universally recognisable experience. The personal has resonance: Blad från höstens arkiv is an echo chamber, and a library, a collection of books. As such, it is a stylish and stylistically appropriate exit from a life among books, some of the most memorable of which he wrote himself.

Translated by David McDuff

Tags: novel

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Clas Zilliacus

A feminist and a dreamer - 30 December 2008

-

About the writer

Clas Zilliacus is a literary scholar and Emeritus professor of Comparative Literature at Åbo Akademi University (Turku).

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.