A walk on the West Side

16 March 2015 | Fiction, Prose

Hannu Väisänen. Photo: Jouni Harala

Just because you’re a Finnish author, you don’t have to write about Finland – do you?

Here’s a deliciously closely observed short story set in New York: Hannu Väisänen’s Eli Zebbahin voikeksit (‘Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits’) from his new collection, Piisamiturkki (‘The musquash coat’, Otava, 2015).

Best known as a painter, Väisänen (born 1951) has also won large readerships and critical recognition for his series of autobiographical novels Vanikan palat (‘The pieces of crispbread’, 2004, Toiset kengät (‘The other shoes’, 2007, winner of that year’s Finlandia Prize) and Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, 2010). Here he launches into pure fiction with a tale that wouldn’t be out of place in Italo Calvino’s 1973 classic The Castle of Crossed Destinies…

Eli Zebbah’s shortbread biscuits

Eli Zebbah’s small but well-stocked grocery store is located on Amsterdam Avenue in New York, between two enormous florist’s shops. The shop is only a block and a half from the apartment that I had rented for the summer to write there.

The store is literally the breadth of its front door and it is not particularly easy to make out between the two-storey flower stands. The shop space is narrow but long, or maybe I should say deep. It recalls a tunnel or gullet whose walls are lined from floor to ceiling. In addition, hanging from the ceiling using a system of winches, is everything that hasn’t yet found a space on the shelves. In the shop movement is equally possible in a vertical and a horizontal direction. Rails run along both walls, two of them in fact, carrying ladders attached with rings up which the shop assistant scurries with astonishing agility, up and down. Before I have time to mention which particular kind of pasta I wanted, he climbs up, stuffs three packets in to his apron pocket, presents me with them and asks: ‘Will you take the eight-minute or the ten-minute penne?’ I never hear the brusque ‘we’re out of them’ response I’m used to at home. If I’m feeling nostalgic for home food, for example Balkan sausage, it is found for me, always of course under a couple of boxes. You can challenge the shop assistant with something you think is impossible, but I have never heard of anyone being successful. If I don’t fancy Ukrainian pickled cucumbers, I’m bound to find the Belorussian ones I prefer.

In the doorway stands another shop assistant. He is, if possible, even busier than his colleague. Clamping the telephone receiver between his shoulder and his chin, he uses his pencil to make frantic scratches on little slips of paper of different colours which he threads on to a spike which already holds dozens of them. He seems to know only two words: of and course. Sometimes he adds the customer’s name: ‘Of course, Miss Reynolds!’

There’s a third person in the shop. You don’t notice him immediately; he seems somehow transparent, as if he had taken on the colours, images and typography of the cardboard boxes behind him. He moves very little, if at all. He examines things, seems to be pondering something, looks at his shoes and smiles to himself. He doesn’t leap back and forth or really even notice the customers. A useless bottom-feeder, you could say. He is Eli Zebbah.

It is hard to guess his age, he bears such a close resemblance in manner and appearance to his cardboard boxes. Eyebrows thick but of colour unknown. Eyes brown or grey-green, indeterminate. And as already noted, he seems always to be somewhere else. With his crepe-soled shoes the colour of milky coffee he continues the long story of his kin.

He does not wear an apron, but a garment which would probably be called a store-coat. It is a front-buttoning garment of no particular colour whose long sleeves nevertheless reveal Eli Zebbah’s hirsute arms. In the breast of the coat is a pocket stuffed with about a dozen pencils of different kinds. The coat is always clean, folded or pressed so that it recalls some geometric thesis. As you pass him on your way to the deeper recesses of the store, he may nod and smile. If someone makes the mistake of asking him about the location or availability of some item, he raises his thumb, points it at the shop assistant and for some reason congratulates the questioner: ‘Mazel tov!’

I often wonder what he is really doing in his store. Why does he tire himself out by standing around among his busy customers as they rush here and there without paying them any attention? Does he believe that there should be some idler to smile in every food shop? He could spend the same time more comfortably elsewhere, playing chess in some park with other old men. Or dash off to rehearse new pieces with his male-voice choir. But the mysteries of entrepreneurship are closed to me.

I visited Zebbah’s store every day. I have always hated the complexities of home delivery and the different methods of calculating tips. I am also always suspicious of products that I haven’t been able to touch for myself. But in addition to lethargy, the heat of New York gives rise to other bad habits. One day I gave in, picked up the receiver and called Eli Zebbah’s grocery store.

As I picked up the phone I leafed through the store’s free catalogue, thinking idly about what I might eat. Cold cucumber soup or something more substantial – maybe cold cuts; something cold, anyway. I thought out my order, but when the familiar shop assistant answered, all the phrases I had prepared were washed away somewhere and I just stammered: ‘I wish, I would, or actually…’. I expected to be met with questions but in fact all I heard was the familiar word-pair: ‘Of course…’. I realised that I was still far from being the genuine city consumer who grandly stabs at the pictures in the catalogue with his finger, simultaneously shouting his order into the receiver. I felt like a toothless beaver.

My order was accepted, however, whatever it may have consisted of. I was toldit would be at my door in about a quarter of an hour. Great, I thought, that went all right. Despite my inhibitions, I had succeeded in ordering my dinner by phone, just like that. I whistled and snapped my fingers in the American way, putting on my dressing gown in order to look relaxed when the doorbell rang.

But the doorbell did not ring. Not after a quarter of an hour, or even three-quarters. I went out to the corridor, sniffed at the neighbours’ doors, checked that my own doorbell was working, went downstairs to ask the doorman whether he had seen a delivery man. No one had been seen and no one had come.

In the end I phoned the store. No one answered. See, I said to myself. You imagined you were clever enough to order your dinner by yourself, as if you didn’t know it was impossible. Get your trainers on and go to a shop, some quite ordinary shop, pick up a basket, pick up the ingredients for your dinner and then join the queue for the till, just like you ought to.

Just as I had reached the front door, my temples beating because I could not find my keys, the phone rang. I answered, but at first I could hear nothing but fizzing and rustling, a kind of enormous sound that you would imagine you would hear only in the stomach of a whale. Then I could make out a few gentle words: ‘Sorry for the Diegos.’ It was Eli Zebbah himself.

‘Both the Diegos are on the wing,’ he said, uttering the words strangely, referring to his Spanish assistants who, no doubt for reasons of convenience, had the same first name. Not understanding anything, I answered, parrot-like, ‘Of course.’

‘Yes, in these heat waves we sell a lot of drinks,’ Eli Zebbah continued. ‘And I have to keep my staff on the run to get even some of them delivered. There is no two-footed being here any more who could bring them to you and so on. So is it OK if I make the delivery myself, as soon as I can,’ asked Zebbah, and I said again, obediently, ‘Of course,’ even though it felt a bit conceited to be pressing the store owner into action on account of such a small order. I managed to utter some involved objection – ‘but of course you don’t have to’ – which Zebbah quashed:

‘I have to make a delivery to your building anyway. Miss Reynolds, you know, and her lame dog…’.

And soon, really very soon indeed, my doorbell rang, perhaps more cheerfully than it ever had before. I went to open the door, and there was Eli Zebbah. He seemed somehow more vivid than in his store. Was it because of the two large plastic bags he was carrying? Or because of his billowing summer shirt, or the smile which had conquered half of his face? On either side of his smile I saw two red discs. Before that broad smile I had to retreat and make way. Without asking where the kitchen was, Eli Zebbah stepped into it as if he knew all the kitchens in the building, which indeed he probably did. But he did ask whether he should sort the things and put them in the fridge, or whether I wanted to do it myself.

I probably replied, ‘Of course.’ I no longer remember, for at the same moment I heard an enormously long yelp, the kind of thing you can hear from the mouth of a terrier left tethered outside a shop. Eli Zebbah had dropped his plastic bags on the floor; he was holding his temples and howling. At the same time he spun round. I did not know what to do. I would have liked to run away. Why was he howling? What had he seen? Was he suffering a migraine attack?

‘That soup tureen,’ he said tearfully, having at last gained control of his voice and pointing at a porcelain dish on the shelf of my rented one-bedroom apartment. ‘That soup tureen! It is from 1941!’

I had rented my apartment furnished and equipped without paying much attention to the plump soup tureen that lived between books and cassettes. When I looked more closely, it appeared tasteless and deliberately old-fashioned. Along its sides ran a slightly abstract swarm of ants carrying on their necks round objects or onions, ingredients for who knows what soup. The tureen’s four feet recalled some animal that liked to live in water. Why had it caused Eli Zebbah to become so distraught?

‘But it’s… it is the Pfaltzgraff Soup Tureen, the 1941 model!’ Eli Zebbah seemed about to fall over under the weight of his words.

‘I’m sure it is, if you say so. So what?’

‘Sell it to me, sell it at once,’ begged Eli Zebbah.

‘It’s not mine. I can’t sell it. You see, nothing here belongs to me. Everything here belongs to Miss Forrest,’ I assured him. ‘I’m living here temporarily. Just temporarily, do you understand?’

‘That’s what I thought,’ said Eli Zebbah, and seemed already to be calming down. ‘No one can get back that which is lost. I broke that soup tureen. Mother died and can never forgive me. Soup Tureen 1941,’ he continued. His voice sank to a whisper, his movements slowed. He sat down on my sofa, probably not even realizing.

This is going to be a long session, I thought. I went into the kitchen, poured a galss of white wine, placed it in front of Eli Zebbah and said:

‘Here you are. Drink. It’s so damned hot, too. I think I’ll pour a glass for myself too.’

Eli Zebbah grabbed the glass and drank the wine down in one gulp. Having emptied the glass, he gazed deep into my eyes and began to speak in a calm, unusually even voice:

‘I’m not deranged, as you no doubt think. That soup tureen really is the work of Pfaltzgraff. A model from the early years of the war. It was one just like it that broke in my hands when I was trying – even though I wasn’t supposed to – to help my mother in serving lunch. Of course I dropped it. The soup spilled on to the carpet, which absorbed the liquid but left everything more solid unfortunately visible. There was my future. In that mush. I was about eleven. I remember how everyone screamed, mother most of all. I loved my mother and her scream hurt me immensely. ‘I will resurrect myself two or three times if you can make it whole,’ my mother shouted, and I promised. I promised. Although at the same time I knew that there is no glue that can mend a Pfaltzgraff that has been broken into a thousand crumbs.’

‘Would you like another glass of wine?’ I asked. At the same time I wondered where the story would lead, marvelling at how spontaneously New Yorkers sit down on other people’s sofas to complain.

‘I am sorry to bother you. But this has to come out now. I see that you are sensitive and receptive, artist that you are. A composer, isn’t it? That soup tureen did it again. It made me naked. I can’t help it. Thank you, yes, I will, it helps. Really, to speak the truth, I hated my mother.’

‘I, on the other hand, lost mine very early on. I didn’t have time to hate her or to love her,’ I said.

‘That is another road. A miserable one too. I am sorry. But my mother did not love me. Or she loved me in her own way, somehow cruelly. As some people treat their toys. Sometimes cuddling them, sometimes tearing them and spitting on them. Guess what she said when I announced that I wanted to go to Yeshiva University to read something or other. I wanted to go to Yeshiva because it wasn’t far from home. No Harvard, but.’

‘I can’t guess,’ I said, rubbing my lips in the hope of bringing forth more words.

‘This is what she said: “Eli, believe me, you will not be going to any university. We all know that you have dough where you should have a brain. I don’t mean any harm, Eli. It’s good dough. It’s dough that you can make this or that out of.” And when I asked what, she answered, with a sweep of her hand: “Those shortbread biscuits of mine. I have the recipe, you have the head. You will make shortbread biscuits and get rich. You won’t be going to any university. You have a dough head, Eli, believe your mother.” That’s exactly what she said…. But look, I don’t have any wine.’

‘Do have some, apologies for my negligence,’ I said, pouring his glass right up to the top. There went my dinner wine.

‘Of course people even get used to mothers who love gambling or betting, but all the same. When you have a mother who tears your future to pieces and offers you shortbread instead, you have to think about it. I decided to change. I had already felt for a long time’ – at this point Eli Zebbah tried to hide behind his glass – ‘don’t be shocked, but this too must come out, that I am more a woman than a man. Of course I’ve noticed these forearms, this premature stoutness, these peeling temples, all the things that don’t go to make up a fine woman. But after I had consulted a couple of quacks and a couple of competent surgeons, I became convinced that a long operation whose Latin name I have glued to the inside of my forehead would open the double doors to my independent future…. May I continue, or will you tell me to go? Can you bear the word “vaginoplasty”,’ said Eli Zebbah, almost pleadingly, pressing his white wine glass against his nose.

What was I supposed to say? In a way I’d had enough. I had had today’s share of New York idiosyncrasy and was a little tired. A sex-change operation was something I didn’t have an opinion on. At least, not now. I nodded and gazed at the two plastic bags, the food they contained.

‘Tell me, in your opinion, am I sufficiently feminine, just tell me. I’m used to it,’ said Eli Zebbah, fluttering his summer shirt and slowly massaging his forearms.

‘I’m sure you know that better yourself,’ I said, and began instinctively to massage my own forearms, as if it were part of the conversation.

‘You won’t. You can’t. OK. I’m used to it. And that’s what happened. Just when it would have been my turn to be born as a woman, just when the preparations had been made, just as I was ready to lie down on the operating table, mother came between me and the doctor. Symbolically, of course, as this happened at home. We were dining together, the two of us, and I finally dared to confess my plans to my mother. I thought she would scream and break something. But no. She sat where she was calmly, holding the cheese knife in her hand, and looked at me acidly if not frankly disparagingly. And then said, beating the air with the knife: “No you won’t, Eli. You will not have that operation. Even an operation will not make you into a woman. Look at yourself. What kind of a woman do you think you would make? A female hippopotamus. I don’t think I’d want to dine with you any more, Eli.”

‘She didn’t accuse me of being gay. Or curse the fact that she wouldn’t be having grandchildren. She just found my plan hopelessly ugly. She did not see in me the woman I wanted to be. She said: “Squeeze your own father into high-heeled shoes and a corset and see your miserable future. You are so similar. Ineffectual hippos. And if you were ever to become a woman, my boy, you would be an abomination to the human race. You would live mostly in a cupboard and would not even be able to knead dough. If, that is, you were to have the operation that you are not going to have. You will not become a woman and Goofy will not become Venus. This is an order. Go and live as a man!’ said my mother, hitting her plate with the cheese knife.

‘I moved out. I took over my uncle’s shop, which was on the skids. I put it on its feet, extended it and – my mother was right – began to be successful. The shortbread biscuits – how funny it all seems now – my mother’s shortbread biscuits and their supposedly secret recipe. Both the Diegos and all their Hispano friends know the recipe. It’s as simple as a traffic sign. Mother died without ever seeing the unbroken Soup Tureen. And now I’m too old to change sex. I weep when I see, on the television, hospitals, clinics, I weep when I see any operation equipment or the greenish hem of an anaesthetist’s coat. Even at the dentist’s I weep, and when the dentist asks, “Does it hurt?”, I say it hurts. Well, now I must go. Would you give me a piece of kitchen roll. I forgot my handkerchief. That Miss Reynolds’ lame dog…. But, all the same, won’t you sell me the Soup Tureen?’

Eli Zebbah rose to his feet and seemed extraordinarily sensible and calm.

‘You can see, that soup tureen is no longer in use. You can see from how it’s been pushed back there to keep those VHS cassettes standing up, do you understand? And who watches cassettes nowadays? And on what machine? I know Miss Forrest well. I will pay well, and you can pay her.’

‘I’d be happy to agree. But I would need Miss Forrest’s permission. Shall we call her? Why haven’t you asked her yourself, since you know her? Would she have said no? And do you really believe in resurrection?’

‘Let it be. I don’t really know whether seeing this thing has done me any good. So, shall I sort the groceries into the fridge, or will you do it yourself?’ asked Eli Zebbah, as if he had suddenly recovered from his life’s worst fever and at once forgotten it.

‘Thank you, I’ll do it myself.’ I didn’t really know what I should have done. Should I have comforted him, saying that a sex-change operation doesn’t always make a person happier? Some people regret them, in the same way as they regret their tattoos. But I remained silent. Or maybe I gazed at the soup tureen. And all at once Eli Zebbah was gone.

There was still one bag at the kitchen door. One bag. I had imagined that both bags were for me. I was mistaken. I went, took the bag and began to unpack its contents. Very quickly I realised that it was not my order. Even in error, I could not have ordered such an enormous quantity of Organic Pet canned dog food. I turned and gazed at the walls. Eli Zebbah would soon be back, I guessed.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

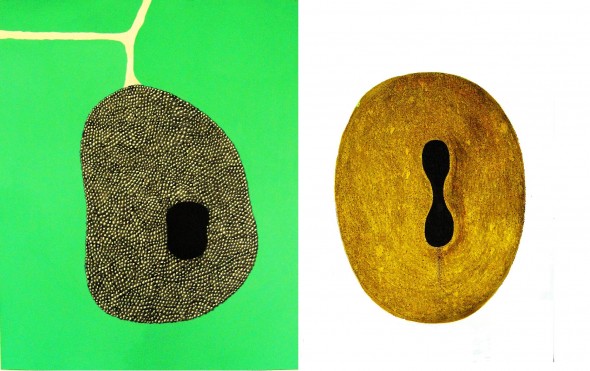

Hannu Väisänen: ‘Green and yellow in March’ (work in progress, oil, 2010)

Tags: short story

No comments for this entry yet