Archive for 2010

Winner of the Susan Sontag Prize

25 December 2010 | In the news

The Susan Sontag Foundation was established in New York in 2004 in memory of the celebrated author and cultural journalist Susan Sontag (1933–2004). The Foundation grants a prize to a young American who translates from other languages into English. In 2010 the prize was awarded for the third time.

Benjamin Mier-Cruz is currently pursuing his PhD in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures at University College Berkeley, with a particular interest in Finland-Swedish modernism and German expressionist poetry. His winning translation proposal is entitled Modernist Missives of Elmer Diktonius – Letters and Poetry of Elmer Diktonius.

Elmer Diktonius (1896–1961) was a rebellious Finland-Swedish avant-garde poet and composer, who was fluent in Finnish as well as his native Swedish. His letters to a wide range of European authors and critics, written between 1919 (the year of the Finnish Civil War) and 1951, reflect the political, artistic and personal developments in Finland and Europe.

The prize ceremony took place first in Helsinki on 5 November in a seminar at the Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland), then at Scandinavia House, New York, on 12 November.

‘Joy and peace prevail…’

25 December 2010 | Fiction, Prose

Dear readers,

to celebrate the change of the year we publish an extract from Aleksis Kivi’s 1870 classic novel, Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers), translated by David Barrett, and a bit of a classic of our own too: it’s a nostalgic glimpse of a Finnish Christmas spent in a humble cottage inhabited, in addition to the eponymous seven brothers, a horse, cat, cockerel and two dogs (at least). Enjoy!

Soila Lehtonen & Hildi Hawkins & Leena Lahti

On a festive night

It is Christmas Eve. The weather has been mild, grey clouds fill the sky, hills and valleys are covered with the snow that has only recently begun to fall. The forest gives out a gentle murmur, the grouse goes to roost in the catkined birch, a flock of waxwings descends on the reddening rowan, while the magpie, daughter of the pine-wood, carries twigs for her future nest. More…

Life through the lens

22 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Let’s go on a little pictorial journey in time with the photographer Erik Hägglund, whose camera went on clicking for 50 years: gentlefolk, peasants, children, old people and village views, beginning almost a hundred years ago in rural western Finland

Ladies in hats: in the 1920s Vörå hats were only used by gentlewomen (and smoking was perhaps a little risqué). Photo: Erik Häggblom

Blickfång. En tidsresa med Vöråfotografen Erik Hägglund (‘In focus. A journey in time with the photographer Erik Hägglund from Vörå’. Red. [Ed. by] Katja Hellman, Meta Sahlström & Monica West. Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2010

Old photographs may prove that what is utterly local can be perfectly universal.

That’s certainly the impression the reader gets by looking at the pictures taken by Eric Hägglund between 1910 and 1960.

The village of Vörå (in Finnish, Vöyri) on the west coast of Finland, near the Ostrobothnian city of Vasa (in Finnish, Vaasa) is traditionally mostly a Swedish-speaking community. Erik Hägglund, born 1884, lived, photographed and died there in 1962. More…

What Finland read in November

17 December 2010 | In the news

In November the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Shokkiaalto (‘Shock wave’, WSOY) topped the Booksellers’ Association of Finland’s list of the best-selling Finnish fiction. Sofi Oksanen’s prize-winning, much-translated 2008 novel Puhdistus (Purge, WSOY), has not left the best-selling list since it was awarded the Finlandia Prize for Fiction this autumn and was now number two.

Riikka Pulkkinen’s novel Totta (‘True’, Otava) was number three, and Tuomas Kyrö’s colllection of episodes from a grumpy old man’s life as told by himself, Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking offense’, WSOY), from last spring, occupied fourth place.

A new novel, Harjunpää ja rautahuone (‘Harjunpää and the iron room’, Otava), by the grand old man of Finnish crime, ex-policeman Matti Yrjänä Joensuu, was number five.

The most popular children’s book was a new picture book about two inventive and curious brothers, Tatu ja Patu supersankareina (‘Tatu and Patu as superheroes’, Otava) by Aino Havukainen and Sami Toivonen.

On the translated fiction list were books by, among others, Ildefonso Falcones, Jo Nesbø, Lee Child, Stephen King, Paulo Coelho and Paul Auster.

The non-fiction list included the traditional annual encyclopaedia Mitä missä milloin (‘What, where, when’, Otava, second place) as well as a political skit entitled Kuka mitä häh (‘Who what eh’, Otava) by Pekka Ervasti and Timo Haapala – the latter sold better, coming in at number one. In November the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes, Shokkiaalto (‘Shock wave’, WSOY) topped the Booksellers’ Association of Finland’s list of the best-selling Finnish fiction.

Högtärade Maestro! Högtärade Herr Baron! [Correspondence between Axel Carpelan and Jean Sibelius,1900–1919]

17 December 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Högtärade Maestro! Högtärade Herr Baron! Korrespondensen mellan Axel Carpelan och Jean Sibelius 1900–1919

Högtärade Maestro! Högtärade Herr Baron! Korrespondensen mellan Axel Carpelan och Jean Sibelius 1900–1919

[My dear Maestro! My dear Herr Baron! Correspondence between Axel Carpelan and Jean Sibelius, 1900–1919]

Red. [Ed. by] Fabian Dahlström

Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2010. 549 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-583-200-9

€40, hardback

‘For whom shall I compose now?’ wrote Finnish composer Jean Sibelius in his diary upon hearing of the death of his good friend Axel Carpelan (1858 –1919). Carpelan was a penniless baron, who considered music and his friendship with Sibelius to be the most vital aspects of his life. Using his natural-born talent and instinct, he gained acceptance as Sibelius’ trusted musical confidant, to whom the composer dedicated his second symphony. Axel came to be known by the wider public in 1986, when his great-nephew, the author Bo Carpelan, made him the protagonist of his award-winning novel entitled simply Axel. This volume, edited by Fabian Dahlström, contains the surviving Swedish-language correspondence between Sibelius and Carpelan, as well as letters to Sibelius’ wife, Aino. Carpelan wrote to her when the composer was too busy. These letters contain interesting details such as Aino Sibelius’ account of the origins of her husband’s violin concerto. The comprehensive foreword to this book sheds additional light on Carpelan’s life.

In with the new?

17 December 2010 | Letter from the Editors

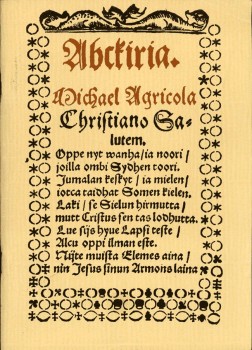

Abckiria (‘ABC book’, 1543): the first Finnish book, a primer by the Reformation bishop Mikael Agricola, pioneer of Finnish language and literature

In August 2010 the American Newsweek magazine declared Finland (out of a hundred countries) the best place to live, taking into account education, health, quality of life, economic dynamism and political environment.

Wow.

In the OECD’s exams in science and reading, known as PISA tests, Finnish schoolchildren scored high in 2006 – and as early as 2000 they had been best at reading, and second at maths in 2003.

Wow.

We Finns had hardly recovered from these highly gratifying pieces of intelligence when, this December, we got the news that in 2009 Finnish kids were just third best in reading and sixth in maths (although 65 countries took part in the study now, whereas in 2000 it had been just 32; the overall winner in 2009 was Shanghai, which was taking part for the first time.)

And what’s perhaps worse, since 2006 the number of weak readers had grown, and the number of excellent ones gone down. More…

Beyond words

15 December 2010 | This 'n' that

Meeting place of the Lahti International Writers' Reunion: Messilä Manor

‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent.’

This famous quotation from the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein has been adapted by the organisers of the Lahti International Writers’ Reunion (LIWRE): the theme of the 2011 Reunion, which takes place in June, will be ‘The writer beyond words’.

‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must write.’ How will the writer meet the limits of language and narration?

‘There are things that will not let themselves be named, things that language can not reach. Our senses give us information that is not tied to language – how can it be translated into writing? And how is the writer going to describe horrors beyond understanding or ecstasy that escapes words? How can one put into words hidden memories, dreams and fantasies that lie suppressed in one’s mind? Does the writer fill holes in reality or make holes in something we only think is reality?

‘Besides literature, there are other forms of interpreting the world; can the writer step into their realms to find new ways of saying things? The surrounding social sphere may put its own limits to writing. What kind of language can a writer use in a world of censorship and stolen words? How does the writer relate to taboos, those dimensions of sexuality, death or holiness that the surrounding world would not want to see described at all? Is it the duty of literature to go everywhere and reveal everything, or is the writer a guardian of silence who does not reveal but protects secrets and everything that lies beyond language?’

The first Writers’ Reunion took place in Lahti at Mukkula Manor in 1963; since then, more than a thousand writers, translators, critics and other book people, both Finnish and foreign, have come to Mukkula to discuss various topics.

In 2009 the theme was ‘In other words’, which inspired the participants to talk about the power of the written word in strictly controlled regimes, about fiction that retells human history and about the differences between the language of men and women, among other things. See our report from the 2009 Reunion; eleven presentations are available in English, too.

On the job

10 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

‘I like my pictures to be realistic and truthful, not that I can satisfactorily define what realism is. The real people in my pictures are in their real surroundings, even though they are posing for me. I see this as a series of encounters. The subjects present their “working role” for me, which I record‚’ says photographer Eija Irene Hiltunen. In these extracts she introduces her project and samples of her photography present people at work in contemporary Finland

Extracts from Työn tekijät. Muotokuvia suomalaisesta työstä. / Doing the job. Portraits of Finnish working life by Eija Irene Hiltunen. Texts: Pasi Alametsä. Translations: Joseph White. Layout: Petri Kuokka & Eija Irene Hiltunen (Avain, 2009)

One of the most important aims of my portraits has been to record an image of the times. I chose work as the common denominator because it relates to the social structure on so many levels.

The ‘visual inventory’ of Weimar Germany by the classic photographer August Sander has been the major inspiration for my work. He made a huge impression on me during my student days. He told of the upheavals of his own time through his portraits, as the old class society broke down, and of the time before the Second World War and the birth of modern Germany. Sander beautifully depicted history through the individual, and his portraits have remained as testaments to life during that era. More…

Ho-ho-no!

10 December 2010 | This 'n' that

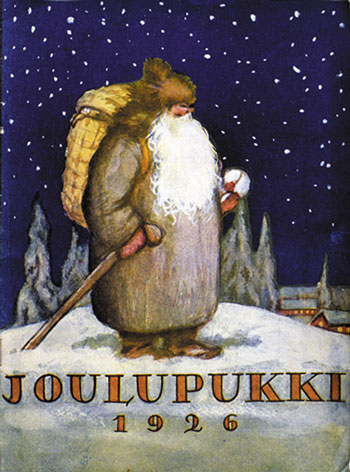

In the olden days: Father Christmas dressed in grey. A Christmas magazine illustration, 1926. Picture: Helsinki City Museum

St Nicholas, Father Christmas, Santa Claus? According to Finns, the benevolent, bearded, reindeer-driving, present-giving figure lives on Korvatunturi fell in Lapland (not at the North Pole, not anywhere else!).

In Finnish his name is Joulupukki, ‘Yule goat’ (or ‘buck’, Old English, bucca). Joulupukki developed from pagan traditions where his predecessor was a creature called Nuuttipukki, ‘Knut’s goat’, which referred to St Knut’s day, originally on 7 January.

The end of Christmas was celebrated by itinerant groups of people visiting houses playing for food and, in particular, booze. Leading them was the scary ‘Knut’s goat’ disguised in horns, a face mask and lambskins, frightening children. If he wasn’t given beer, he could steal the spigot from the beer barrel or beat people with a bunch of twigs.

This tradition was popular until the beginning of the 20th century, when the good Joulupukki replaced his old bad post-Christmas counterpart, shedding his horns and mask. However, when he came to people’s homes on Christmas Eve to bring presents, he still wore a fur coat, was heavily bearded and might still carry both twigs and gifts – so children had indeed better watch out how they behaved all year.

Naughty or nice? A new full-length Finnish film directed by Jalmari Helander entitled Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale was released internationally in early December.

In this Yuletide film the central figure of the mundane Christmas celebrations is not the red-dressed, jolly Santa we know, but ‘a sinister old codger who chews off ears and whose demon minion kidnaps innocent children. Ho ho no!’, as Jeannette Catsoulis reported in the New York Times.

‘Rare Exports is an enormously entertaining and unpredictable Yuletide romp packed with sly wit, solid scares and naked geriatrics,’ said Tom Huddleston of Time Out London.

Frank Lovece, in Film Journal International, wrote: ‘Some human and reindeer gore make this inappropriate for young children, as much as the movie’s boy-hero denouement may suggest otherwise. But for anyone who needs an inoculation of humbug to counter artificial sentiment, or who simply likes to smoke their Christmas cheer or put it in brownies, this off-kilter return to roots is a welcome gift.’

The plot involves a mysterious block of ice that has been unearthed in Lapland, sprouting a pair of horns. Children begin to disappear, reindeer are found killed. A ten-year-old boy finds out what’s happening, and he and his dad take up fighting back. ‘Wicked fun in the manner of a 21st century Grimm’s fairy-tale,’ said Chris Barsanti of filmcritic.com. ‘Exuberantly pagan images,’ wrote Jeannette Catsoulis.

Well, Rare Exports was in fact filmed in Norway: Finnish fells are low and unimpressive in comparison to the higher Norwegian fells and mountains. Joulupukki’s home on Korvatunturi is particularly difficult to access, as the Russian border cuts through this formation of fells, which is also a part of a nature conservation area.

Santa’s red, fur-lined outfit is a comparatively recent invention, by the way: it became popular in the United States in an advertising campaign for Coca-Cola in 1931. By a trick of fate, though, the image was designed by one Haddon Sundblom who was of Finnish (Åland) origin.

So, what’s the truth about Joulupukki ? Could it be that an incarnation of the ancient horned shaman-like creature might still dwell in the depths of that faraway Lapland fell, and that the Coca-Cola man on whose lap your kid is sitting, listing his or her wishes, is just some commercial impostor?

Kai Ekholm & Yrjö Repo: Kirja tienhaarassa vuonna 2020 [The book at the crossroads in 2020]

10 December 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kirja tienhaarassa vuonna 2020

Kirja tienhaarassa vuonna 2020

[The book at the crossroads in 2020]

Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2010. 205 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-495-158-6

€29, paperback

This book looks at Finnish book publishing and its likely rate and direction of change. The future of the Finnish industry looks slightly more favourable than similar international forecasts have made out, although there have been some shake-ups in the Finnish book world too. The authors point out that while the decrease of reading as a leisure pursuit appears to be part of a long-term international trend, many feared for the future of the book in previous centuries as well. Book production and distribution, as well as changes undergone by various genres, are illustrated through a variety of statistics. They also go a long way towards explaining whether the publishing industry’s current difficulties are intrinsic or extrinsic in origin. The authors strive to find new perspectives to get away from a fear of the online world. The renewable publishing and reading culture envisioned by the authors will benefit from the novelty and efficiency of electronic publishing and will reinforce traditional knowledge. Professor Kai Ekholm is the Director of the National Library of Finland; Yrjö Repo is a researcher and statistician.

Profession: author

10 December 2010 | In the news

Alexandra Salmela, 30, won the Helsinki newspaper Helsingin Sanomat Literature Prize 2010 for best first work, worth €15,000.

Her novel 27 eli kuolema tekee taiteilijan (’27 or death makes one an artist’, Teos) depicts a young woman’s search for her own place and calling in the world. Angie leaves her city of study, Prague, for a small Finnish village, wishing to become an author. Among the narrators are also a soft piggy toy, a cat and a car.

With degrees from both the Theatre Academy of Bratislava and Charles University of Prague, the Slovak-born Salmela majored in Finnish and Finnish literature. She has lived in Tampere, Finland for the past four years. In her opinion Finns should scrap the myth about their difficult language.

The jury chose the winner from 80 debut works, finding Salmela’s novel highly original in its imaginative narrative techniques and language.

Once more: Sofi Oksanen’s novel wins a prize

10 December 2010 | In the news

Sofi Oksanen (born 1977) has received the Europe Book Prize, worth €10,000, for her novel Puhdistus (Purge, 2008). Chosen from a shortlist of eight works, the prize was awarded by the ex-chairman of the European Union Commission, Jacques Delors, in Brussels on 9 December.

The European Book Prize jury is made up of European journalists and correspondents and was chaired by the German film director Volker Schlöndorff. According to the jury, Puhdistus is ‘a brave and painful exploration into the traumas of the Estonian history’.

The prize was awarded this year for the fourth time. The author expressed her appreciation of the prize by saying Europeanness for her signifies freedom of speech, respect for human rights and the will of sustaining these fragile and easily damaged values.

Stories in the stone

2 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

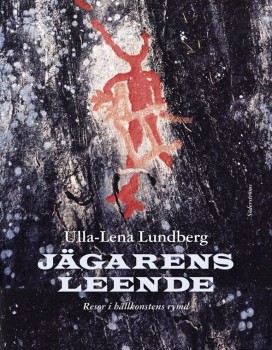

Extracts from Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010)

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘I think about this often – I who love painting but who still chose a career that involves me sitting and hammering away, day in and day out, like a true rock-carver,’ writes author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg in her new book on the art of the primeval man

When the children of Israel went into Babylonian captivity, hanging up their harps on the willow-trees and weeping as they remembered Zion, my sister and I were already sitting by the rivers of Babylon. We knew how they felt. Our father was dead and we had been sent away from our home. We sat there clinging to each other, or rather I was the one clinging to Gunilla, and she had to try to rouse herself and find something for us to do, to give us something else to think about. More…

Heartstone

2 December 2010 | Reviews

Ulla-Lena Lundberg

‘Knowledge enhances feeling’ is a motto that runs through the whole of Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s oeuvre – both her novels and her travel-writing, covering Åland, Siberia and Africa.

In her trilogy of maritime novels (Leo, Stora världen [‘The wide world’], Allt man kan önska sig [‘All you could wish for’], 1989–1995) she used the form of a family chronicle to depict the development of sea-faring on Åland over the course of a century or so. She gathered her material with historical and anthropological methodology and love of detail. The result was entirely a work of quality fiction, from the consciously old-fashioned rural realism of the first volume to the contradictory postmodern multiplicity of voices in the last – all of it in harmony with the times being depicted.

When Lundberg (born 1947) takes us underground or up onto cliff-faces in her new documentary book, Jägarens leende. Resor i hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’), in order to consider cave- and rock-paintings in various parts of the world, she also reveals a little of the background to this attitude towards life that takes such delight in acquiring knowledge – an attitude that is familiar from many of the protagonists of her novels. More…

Finland(ia) of the present day

2 December 2010 | In the news

Mikko Rimminen. Photo: Heini Lehväslaiho

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2010, worth €30,000, was awarded on 2 December to Mikko Rimminen (born 1975) ; his novel Nenäpäivä (‘Nose day’, Teos) was selected by the cultural journalist and editor Minna Joenniemi from a shortlist of six.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (Marianne Bargum, former publishing director of Söderströms, researcher and writer Lari Kotilainen and communications consultant Kirsi Piha) shortlisted the following novels:

Joel Haahtela: Katoamispiste (‘Vanishing point’, Otava), Markus Nummi: Karkkipäivä (‘Candy day’, Otava), Riikka Pulkkinen: Totta (‘True’, Teos), Mikko Rimminen: Nenäpäivä (‘Nose day’, Teos), Alexandra Salmela: 27 eli kuolema tekee taiteilijan (’27 or death makes an artist’, Teos) and Erik Wahlström: Flugtämjaren (in Finnish translation, Kärpäsenkesyttäjä, ‘The fly tamer’, Schildts). Here’s the FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange link to the jury’s comments.

Joenniemi noted the shortlisted books all involve problems experienced by people of different ages. How to be a consenting adult? How do adults listen to children? Contemporary society has been pushing the age limits of ‘youth’ upwards so that, for example, what used to be known as middle age now feels quite young. And, for example, in Erik Wahlström’s Flugtämjaren (now also on the shortlist for the Nordic Literature Prize 2011) the aged, paralysed 19th-century author J.L. Runeberg appears full of hatred: being revered as Finland’s national poet didn’t make him particularly noble-minded.

According to Joenniemi, Rimminen’s novel ‘takes a stand gently’ in its portrayal of contemporary life – in a city where a lonely person’s longing for human contacts takes on tragicomical proportions. Joenniemi finds Rimminen’s language ‘uniquely overflowing’. Its humour poses itself against the prevailing negative attitude, turning black into something lighter.

Rimminen has earlier published two collections of poems and two novels (Pussikaljaromaani, ‘Sixpack novel’, 2004, and Pölkky, ‘The log’, 2007) . Pussikaljaromaani has been translated into Dutch, German, Latvian, Russian and Swedish.