Archive for December, 2012

In praise of idleness (and fun)

21 December 2012 | Letter from the Editors

As the days grow shorter, here in the far north, and we celebrate the midwinter solstice, Christmas and the New Year, everything begins to wind down. Even here in Helsinki, the sun barely seems to struggle over the horizon; and the raw cold of the viima wind from the Baltic makes our thoughts turn inward, to cosy evenings at home, engaging in the traditional activities of baking, making handicrafts, reading, lying on the sofa and eating to excess.

It is a time to turn to the inner self, to feed the imagination, to turn one’s back on the world of effort and achievement. To light a candle and perhaps do absolutely nothing – which can in itself be a form of meditation.

That’s what we at Books from Finland will be trying to do, anyway. Support in our endeavour comes from an unlikely quarter. In 1932 the British philosopher Bertrand Russell published an essay entitled ‘In Praise of Idleness’, in which he argued cogently for a four-hour working day. ‘I think that there is far too much work done in the world,’ he wrote; ‘that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous’.

Russell was no slouch, as his list of publications alone shows. But his argument was a serious one, and we mean to put it into practice, at least over the twelve days of Christmas. ‘The road to happiness and prosperity,’ he wrote, ‘lies in an organised diminution of work.’ More…

Good school, bad pupils, or vice versa?

21 December 2012 | This 'n' that

Number one: Finland. The Pearson analysis, 2012

Finland is used to feeling pretty good about itself when it comes to education. In the widely respected PISA tests – the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s exams in science and literacy – Finnish schoolchildren have, since the turn of the century, been outperforming most of their peers.

A shock came in 2009 when the tests revealed that Finnish kids were only third-best at reading, and sixth in maths; but by this time they were competing against the newly participating Asian countries, with their huge concentration on education.

Now, however, a new league table, drawn up by the education publishers Pearson, places Finland right at the top (2006–2010, 40 countries). Second place is held by South Korea; third is Hong Kong. The Pearson analysis uses a broader set of criteria, using not just test results but broader measures such as how many people go to university. In a result that is causing some puzzlement in the United Kingdom, Britain is rated sixth. Entirely, say critics, because British universities are so easy to get into.

The results are indeed flattering to Finland – but Finnish children’s motivation to learn is among the weakest in the survey’s countries. In reading, mathematics and the sciences Finns’ attitudes and application were low. It looks as if Finnish children consider school a place to hang out with their friends, not a place for teaching and learning. Countries where competition is stronger breed different attitudes.

So here’s the Finnish paradox: kids here hate school – yet still end up at the top of the list.

Must be something in the water.

Pertti Lassila: Metsän autuus. Luonto suomalaisessa kirjallisuudessa 1700–1950 [Bliss of the forest. Nature in Finnish literature 1700–1950]

21 December 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Metsän autuus. Luonto suomalaisessa kirjallisuudessa 1700–1950

Metsän autuus. Luonto suomalaisessa kirjallisuudessa 1700–1950

[Bliss of the forest. Nature in Finnish literature 1700–1950]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (The Finnish Literature Society), 2011, 260 p.

ISBN 978-952-222-322-7

€35, paperback

Culture and art are relatively recent phenomena in Finland, but the forests, lakes and swamps have been here forever: national introspection has therefore always revolved around different ways of interpreting nature. National poet J.L. Runeberg (died 1877) romanticised the wilderness of the north and its starving inhabitants; pragmatic national philosopher J.V. Snellman (died 1881) rejoiced in the advances of continental culture in the farming regions of southwest Finland. Attempts to combine these two stances characterised the building of political and cultural ideas. Literary researcher Pertti Lassila follows the theme of nature through Finnish- and Swedish-language literature, including almost all major works up until the 20th century and some of the most important ones from the last century. His book is, at the same time, a description of the flow of ideas from the centre to the periphery, from the French classicist Carl Philip Creutz, author of hedonistic pastoral poetry, to Joel Lehtonen, writer of modern epics, whose endless pessimism was a largely constructed attempt to shape the split between nature and the alienated citizen of the 20th century; how successful he was is debatable. Nature remains a major theme in Finnish literature.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Pilvi Torsti: Suomalaiset ja historia [The Finns and history]

21 December 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Suomalaiset ja historia

Suomalaiset ja historia

[The Finns and history]

Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2012. 303 p., ill .

ISBN 978-952-495-264-4

€37, paperback

Dr Pilvi Torsti’s book is based on a project aimed at finding out through extensive interviews what ordinary Finns think of Finland’s history (especially in the period of independence since 1917), and how important it is to them, rather than how much they know about it. The large majority of the respondents believe that history forms part of general knowledge and also explains the present. They also attached importance to their own family history, while Finnish history was seen as a story of progress. History undertaken as a hobby is more common in Finland than in some comparable countries. When asked about the most important issues in the country’s history, the education system came top of the list in more than 75 per cent of the responses, and the Winter War (1939–40) and universal suffrage (1906) in more than half. The comprehensive presentation of research data and conclusions is leavened by the interviewees’ statements, as well as by drawings. More information about this many-faceted study can be found on the project’s website.

Translated by David McDuff

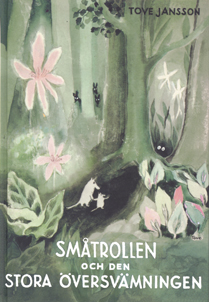

Moomins, and the meanings of our lives

21 December 2012 | This 'n' that

The first ever Moomin story, 1945

Tove Jansson’s Moomin books are widely cherished by children and adults alike. They are funny and charming yet haunting and profound. Lovable Moomintroll; practical and sensible Moominmama; spiky Little My; the terrifying yet complex monster, Groke – Jansson’s creations linger in the mind.

The first ever Moomin book – The Moomins and the Great Flood (Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen, 1945) – was published in the UK in October by Sort Of Books, but Jansson’s writing for adults is also achieving recognition in the English-speaking world.

A Winter Book, a selection of 20 stories by Jansson (Sort Of Books, 2006) was the trigger for a recent event on London’s South Bank. Along with journalist Suzi Feay and writer Philip Ardagh, I was invited to talk about Jansson’s work in general and about these stories in particular.

As Ali Smith notes in her fine introduction to the collection, the texts are ‘beautifully crafted and deceptively simple-seeming’. They are, as she puts it ‘like pieces of scattered light’. She also refers to the stories’ ‘suppleness’ and ‘childlike wilfulness’.

‘The Dark’, for example, offers an apparently random set of snapshots of childhood. Arresting images abound – swaying lamps over an ice rink, swirls in the pattern of a carpet that turn into terrible snakes – to create a tapestry of childhood. It’s like a dream: of ice and fire, fear and safety, a mixture that recalls the secure yet scary world of Moomin valley.

‘Snow’, too, conjures childhood fear. The house that features in this story is unhomely or uncanny, to refer to Freud, and seems haunted by the ghosts of other families. The story ends with the shared resolution between mother and child to return to a place of safety: ‘So we went home.’

Tove Jansson (1914–2001)

The combination of scariness and safety, of comfort and unease, is one of the things that makes Jansson (1914–2001) such a powerful writer, not only for children – although questions of security and fear might have especial resonance in early life – but also for adults, who continue to be haunted by the unknown, but also tempted by it.

The South Bank event also gave participants and audience the chance to talk about other works by Jansson. The Summer Book (Sommarboken, 1972) notably, is a delicate and deft evocation of a summer spent on an island.

The narrative charts the relationship between a grandmother and granddaughter, and at the same time probes such profoundly human questions as love and loss, hope and change and continuity. As always in Jansson, the descriptions are sharp and crisp, and the writing is at once spare and suggestive.

Novels like Fair Play (Rent spel, 1989) and The True Deceiver (Den ärliga bedragaren, 1982) reveal Jansson’s subversive, sly, and subtle sides, which sit alongside her playfulness, warmth, and humour to create a unique aesthetic. Fair Play is a book about the relationship between two women; it’s tender, funny and thoughtful. Never sentimental, it is nonetheless moving. And it’s quietly subversive in its matter-of-fact depiction of a same-sex relationship.

The True Deceiver is set in a snowbound hamlet. A young woman fakes a break-in at the house of an elderly artist, a children’s book illustrator, and a strange dynamic develops between the two women. It’s a book about being outside, about not belonging. The relationship between the women, which is never fully resolved or explained, is especially fascinating.

Jansson excels at showing the human need for both company and privacy, intimacy and autonomy. And her work is profoundly philosophical. In very light, nimble narratives, Jansson explores the meanings of our lives.

Coming up…

14 December 2012 | This 'n' that

Natural art: hexaconal dendrite snowflake, magnified by an electron microscope and coloured. Photo: Beltsville Agricultural Research Unit, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture / Wikimedia Commons

Stop press: in a change to our advertised schedule, columnist Jyrki Lehtola reports on last week’s Finnish Independence Day shindig.

So our new Letter from the Editors, with appropriately festive themes, will appear next week.

Mind the gaffe

14 December 2012 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

Celebrating Finnish Independence Day is a serious business involving lots of handshakes and plenty of pitfalls for the unwary, observes columnist Jyrki Lehtola. But luckily there’s plenty of fun to be had for ordinary Finns in complaining about it all

When Finland makes the news, it’s usually because of a national tragedy or something odd we do. The latter ripe fodder for filling the blank pages of the international media on slow news days includes such things as the Finnish penchant for competitions in such sporting events as Wellington boot /mobile phone tossing (saappaan- / kännykänheitto) and wife carrying (akankanto).

We have another odd national tradition, although it has never received as much international recognition as the fact that we carry our wives competitively. This time- honoured custom repeats annually on the sixth of December, when we close our shops and barricade ourselves gloomily within our homes. Its name is Independence Day. More…

Coming in from the cold

13 December 2012 | This 'n' that

Kulttuurisauna in Helsinki: design by Tuomas Toivonen and Nene Tsuboi

Kulttuurisauna, ‘The culture sauna’, will soon be opened in Helsinki as a part of the World Design Capital 2012 programme. The idea was developed into a project by architect Tuomas Toivonen and designer Nene Tsuboi, a Finnish-Japanese couple who will also run the sauna.

‘When we started considering the idea of building a public sauna in Helsinki, I realised that my dream job is to run a public sauna – offering people a place for cleansing, bathing and sharing quiet togetherness. We have been working in the field of design and architecture for 10 years now, and felt that we can use all of our skills in this project, developing a new public sauna in Helsinki; as a building, as a service and as an environment. By doing this, we want to contribute to the city, participating in making Helsinki more interesting and enjoyable’, says Tsuboi. More…

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012

13 December 2012 | In the news

Ulla-Lena Lundberg. Photo: Cata Portin

The winner of the 29th Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, worth €30,000, is Ulla-Lena Lundberg for her novel Is (‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms), Finnish translation Jää (Teos & Schildts & Söderströms). The prize was awarded on 4 December.

The winning novel – set in a young priest’s family in the Åland archipelago – was selected by Tarja Halonen, President of Finland between 2000 and 2012, from a shortlist of six.

In her award speech she said that she had read Lundberg’s novel as ‘purely fictive’, and that it was only later that she had heard that it was based on the history of the writer’s own family; ‘I fell in love with the book as a book. Lundberg’s language is in some inexplicable way ageless. The book depicts the islanders’ lives in the years of post-war austerity. Pastor Petter Kummel is, I believe, almost the symbol of the age of the new peace, an optimist who believes in goodness, but who needs others to put his visions into practice, above all his wife Mona.’

Author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg (born 1947) has since 1962 written novels, short stories, radio plays and non-fiction books: here you will find extracts from her Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010). Among her novels is a trilogy (1989–1995) set in her native Åland islands, which lie midway between Finland and Sweden. Her books have been translated into five languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (researcher Janna Kantola, teacher of Finnish Riitta Kulmanen and film producer Lasse Saarinen) shortlisted the following novels: Maihinnousu (‘The landing’, Like) by Riikka Ala-Harja, Popula (Otava) by Pirjo Hassinen, Dora, Dora (Otava) by Heidi Köngäs, Nälkävuosi (‘The year of hunger’, Siltala) by Aki Ollikainen and Mr. Smith (WSOY) by Juha Seppälä.

Markku Kuisma & Teemu Keskisarja: Erehtymättömät. Tarina suuresta pankkisodasta ja liikepankeista Suomen kohtaloissa 1862–2012 [The infallible ones. The story of the great bank war and Finland’s commercial banks, 1862–2012]

13 December 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Erehtymättömät. Tarina suuresta pankkisodasta ja liikepankeista Suomen kohtaloissa 1862–2012

Erehtymättömät. Tarina suuresta pankkisodasta ja liikepankeista Suomen kohtaloissa 1862–2012

[The infallible ones. The story of the great bank war and Finland’s commercial banks, 1862–2012]

Helsinki, WSOY, 2012. 496 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-39228-7

€ 38.80, hardback

Historians Markku Kuisma and Teemu Keskisarja’s lively book tells the story of Finland’s commercial banks, from the establishment of the first one in 1862. A recurrent theme in the book is the competition between the two largest. With their relations to and allies in the business world the banks have had an important social and political influence in the country. The commercial banking institutions have had more prominence than others, and the directors have often been strong personalities. Most of the emphasis in the book is placed on the final decades of the 20th century. In the 1980s the financial markets were deregulated, and the boom of the ‘crazy years’ of the bank war was accelerated by share trading and cornering. In 1995 the recession caused by the banking crisis led to the merger of the two largest commercial banks. A few years later this new institution merged with a Swedish one, and the large new bank Nordea subsequently expanded to neighbouring countries. The age of large national commercial banks in Finland was over.

Translated by David McDuff

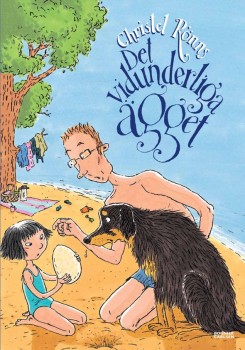

Finlandia Junior Prize 2012

5 December 2012 | In the news

The Finlandia Junior Prize 2012 went to the illustrator and writer Christel Rönns for her book Det vidunderliga ägget (‘The extraordinary egg’, Söderströms & BonnierCarlsen).

The Finlandia Junior Prize 2012 went to the illustrator and writer Christel Rönns for her book Det vidunderliga ägget (‘The extraordinary egg’, Söderströms & BonnierCarlsen).

The winner was chosen from the shortlist of six by the film director and actor Mari Rantasila. Awarding the prize, worth €30,000, on 29 November she said:

‘The book has masterly, original and clear illustrations that support the story; the drawings include amusing details. It is refreshing to read a story about a family that all pulls in the same direction.

‘Det vidunderliga ägget deals with important matters, in a way that is suitable for small children: toleration of difference and the difficulty of loss, underlining that difference is not frightening or negative.’

The following five books also made it to the shortlist: Nörtti: new game (‘The nerd: new game’, Otava), about a schoolboy, bullying and social media by Aleksi Delikouras, Tatu ja Patu pihalla (‘Tatu and Patu on the yard’, Otava), a new picture book in the series about two curious little boys by Aino Havukainen and Sami Toivonen, Hurraa Helsinki! (‘Hurrah Helsinki!’, Tammi), a picture book about Helsinki by Karo Hämäläinen and Salla Savolainen, Puhelias Elias (‘Talkative Elias’, Tammi), an illustrated story about a little boy and his parent’s separation by Essi Kummu and Marika Maijala, and Kirkkaalla liekillä (‘With a bright flame’, Robustos), about 15-year-old Maaria, who lives through difficult times, by Venla Saalo.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2012

5 December 2012 | In the news

‘It is one of the rules of quality journalism that writers aim for even-handed and impartial reporting, but at the same time challenge their respondents to account for their actions. Writers should also have the capacity for in-depth reporting and analysis,’ said Janne Virkkunen, former Editor-in-Chief of Helsingin Sanomat newspaper on 8 November, as he announced the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction, worth €30,000.

‘It is one of the rules of quality journalism that writers aim for even-handed and impartial reporting, but at the same time challenge their respondents to account for their actions. Writers should also have the capacity for in-depth reporting and analysis,’ said Janne Virkkunen, former Editor-in-Chief of Helsingin Sanomat newspaper on 8 November, as he announced the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction, worth €30,000.

The winner, Syötäväksi kasvatetut. Miten ruokasi eli elämänsä (‘Grown to be eaten. How your food lived its life’, Atena) by the young journalist Elina Lappalainen, is her first book.

‘The book could have fallen prey to the sensationalism of which we all probably have experience in the media, at least. This writer was able to avoid the temptation,’ Janne Virkkunen said.

The other works on the shortlist of six were as follows: Arabikevät (‘The Arab spring’, Avain), a study of spring 2011 in the Arab world by Lilly Korpiola and Hanna Nikkanen, Norsusta nautilukseen. Löytöretkiä eläinkuvituksen historiaan (‘From the elephant to the nautilus. Explorations into the illustration of animals’, John Nurminen Foundation) by Anto Leikola, Kevyt kosketus venäjän kieleen (‘A light touch to the Russian language’, Gaudeamus) by professor of Russian Arto Mustajoki, Karhun kainalossa. Suomen kylmä sota 1947–1990 (‘Under the arm of the Bear. Finland’s Cold War 1947–1990’, Otava) by Jukka Tarkka and Markkinat ja demokratia. Loppu enemmistön tyrannialle (‘Market and democracy. The end of the tyranny of the majority’, Otava) by banker Björn Wahlroos.

Fredrik Lång: Av vad är lycka. En Krösusroman [From what is happiness. A Croesus novel]

4 December 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Av vad är lycka. En Krösusroman

Av vad är lycka. En Krösusroman

[From what is happiness. A Croesus novel]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 221 p.

ISBN 978-951-523-002-7

€20.25, hardback

What is happiness? According to the Western thought, happiness is to have, to own, and whenever possible to get even more – it is interesting to find out what our forefathers thought about the question before it was answered. This is precisely what Fredrik Lång does in this novel, the best since the ancient-inspired Mitt liv som Pythagoras (‘My life as Pythagoras’, 2005). Lång describes the Lydian king Kroisos, the richest man of his day, and his attempt to overthrow the wise Greek Solon’s idea that moderation and a contemplative lifestyle lead to happiness. Even if the driving force behind this novel is philosophical, it is brought alive with graphic depictions, extravagant battlefield scenes, intrigue and heartrending romance. Lång’s narrative is often ironic or comical, yet it still manages to emphasise the hard lives of its characters and the complete and utter inequality between master and slave, rich and poor, man and woman. Despite the immersion in the past, it is his own time Lång writes about, sometimes via shameless anachronism, sometimes subtle hints.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Form follows fun

4 December 2012 | Non-fiction, Reviews

The house that the artist built: ‘Life on a leaf’ (2005–2009, Turku). Photo: Vesa Aaltonen

Jan-Erik Andersson: Elämää lehdellä [Life on a leaf]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2012. 248 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5872-82-4

€42, hardback

‘I am Leaf House –

root house, sky house.

Enter me, be safe

And wander, dream.

The artist’s I is all our eyes….’

In the garden: red ‘apple’ benches designed by the English artist Trudy Entwistle. Photo: Matti A. Kallio

We all live – exceptions are really rare – in cubes. Not in cylinders or spheres, let alone in buildings of organic shapes like flowers or leaves; and houses in the shape of a shoe, for example, belong to the fairy-tale world, or perhaps to surrealism.

Artist Jan-Erik Andersson wanted to build a fairy-tale house in the shape of a leaf, and that is what he did (2005–2009), together with his architect partner Erkki Pitkäranta. Instead of the geometry of modernist architecture, he is inspired by the organic forms of nature.

Andersson’s house project, entitled ‘Life on a leaf’, also became an academic project, resulting in a dissertation at Finnish Academy of Fine Arts and now a book, including a detailed journal of the building process itself. The artist was at first advised, by a professor of architecture, not to proceed with his building project – he wouldn’t ‘like living in the house’, he was told. More…