Author: Emily Jeremiah

Moomins, and the meanings of our lives

21 December 2012 | This 'n' that

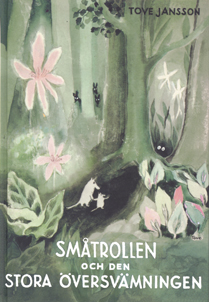

The first ever Moomin story, 1945

Tove Jansson’s Moomin books are widely cherished by children and adults alike. They are funny and charming yet haunting and profound. Lovable Moomintroll; practical and sensible Moominmama; spiky Little My; the terrifying yet complex monster, Groke – Jansson’s creations linger in the mind.

The first ever Moomin book – The Moomins and the Great Flood (Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen, 1945) – was published in the UK in October by Sort Of Books, but Jansson’s writing for adults is also achieving recognition in the English-speaking world.

A Winter Book, a selection of 20 stories by Jansson (Sort Of Books, 2006) was the trigger for a recent event on London’s South Bank. Along with journalist Suzi Feay and writer Philip Ardagh, I was invited to talk about Jansson’s work in general and about these stories in particular.

As Ali Smith notes in her fine introduction to the collection, the texts are ‘beautifully crafted and deceptively simple-seeming’. They are, as she puts it ‘like pieces of scattered light’. She also refers to the stories’ ‘suppleness’ and ‘childlike wilfulness’.

‘The Dark’, for example, offers an apparently random set of snapshots of childhood. Arresting images abound – swaying lamps over an ice rink, swirls in the pattern of a carpet that turn into terrible snakes – to create a tapestry of childhood. It’s like a dream: of ice and fire, fear and safety, a mixture that recalls the secure yet scary world of Moomin valley.

‘Snow’, too, conjures childhood fear. The house that features in this story is unhomely or uncanny, to refer to Freud, and seems haunted by the ghosts of other families. The story ends with the shared resolution between mother and child to return to a place of safety: ‘So we went home.’

Tove Jansson (1914–2001)

The combination of scariness and safety, of comfort and unease, is one of the things that makes Jansson (1914–2001) such a powerful writer, not only for children – although questions of security and fear might have especial resonance in early life – but also for adults, who continue to be haunted by the unknown, but also tempted by it.

The South Bank event also gave participants and audience the chance to talk about other works by Jansson. The Summer Book (Sommarboken, 1972) notably, is a delicate and deft evocation of a summer spent on an island.

The narrative charts the relationship between a grandmother and granddaughter, and at the same time probes such profoundly human questions as love and loss, hope and change and continuity. As always in Jansson, the descriptions are sharp and crisp, and the writing is at once spare and suggestive.

Novels like Fair Play (Rent spel, 1989) and The True Deceiver (Den ärliga bedragaren, 1982) reveal Jansson’s subversive, sly, and subtle sides, which sit alongside her playfulness, warmth, and humour to create a unique aesthetic. Fair Play is a book about the relationship between two women; it’s tender, funny and thoughtful. Never sentimental, it is nonetheless moving. And it’s quietly subversive in its matter-of-fact depiction of a same-sex relationship.

The True Deceiver is set in a snowbound hamlet. A young woman fakes a break-in at the house of an elderly artist, a children’s book illustrator, and a strange dynamic develops between the two women. It’s a book about being outside, about not belonging. The relationship between the women, which is never fully resolved or explained, is especially fascinating.

Jansson excels at showing the human need for both company and privacy, intimacy and autonomy. And her work is profoundly philosophical. In very light, nimble narratives, Jansson explores the meanings of our lives.