A perfect storm

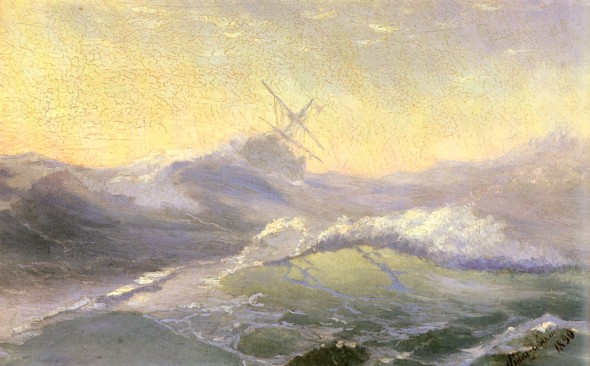

Bracing the waves. Ivan Aivazovsky, 1890.

According to Petri Tamminen, Finns are burdened by the need to succeed. Instead, he argues they should learn to fail better.

Part comedy, part tragedy, part picaresque novel, with a dash of Joseph Conrad – Tamminen’s new book, Meriromaani. Eräitä valoisia hetkiä merikapteeni Vilhelm Huurnan synkässä elämässä (‘A maritime novel. A few bright moments in Captain Vilhelm Huurna’s sombre life’, Otava, 2015) is set in an indeterminate seafaring past of the 18th or 19th century. It tells the story of the world’s most unsuccessful sea captain, Vilhelm Huurna who, one by one, sinks all the ships he commands.

Tamminen (born 1966) is a master of very short prose – this miniature novel is a a huge undertaking in the context of his work as a whole – and at Books from Finland we’re big fans. You can read more of his work here.

We join the story as Huurna, leaving behind him a failed romance in Viipuri, sets sail for Archangel, on the far north coast of Russia.

![]()

An excerpt from Meriromaani. Eräitä valoisia hetkiä merikapteeni Vilhelm Huurnan synkässä elämässä (‘A maritime novel. A few bright moments in Captain Vilhelm Huurna’s sombre life’, Otava, 2015)

The sun shone on the Arctic Ocean night and day, and the voyage went amazingly well, as did all the tasks and jobs that Huurna particularly feared beforehand.

Ships lay in Archangel harbour like objects on a collector’s shelf. They were waiting for timber cargo from the local sawmills where work was at a standstill because the mills lacked the machines and machine parts that they were now bringing them. When their cargo had been unloaded and the machines installed, timber began arriving from the sawmills. They found themselves at the end of the queue, and after the other ships had departed, one by one, they were still waiting in Archangel. That suited Huurna; in the first few days of his stay he had become acquainted with two English merchants and, through them, had received invitations to parties. He had stood in salons drinking toasts to the honour of this or that and made the acquaintance of some charming ladies into whose eyes he wished to gaze another time. He was quite moved by the whirl of this unexpected social life, and brightened at the thought that there was really nothing to complain about in his life apart from the fact that he happened still to be a bachelor.

*

He had always considered himself to have a poor memory, but he remembered everything about all the women who had ever rejected him, including the weather and the light conditions, and he remembered the roads along which he had walked afterwards, recalling his failure and his clumsiness.

On those lonely roads he always realised how little he had been able to say and how abruptly he had said the little he did utter, and it annoyed and amused him so much that he grimaced, and he experienced a sudden need to talk to someone.

In Archangel, he remembered the expressions and the poses and the weather of Viipuri. He hadn’t been rejected in Viipuri, but he had been bidden farewell: it was in Viipuri that he had met the charming young lady with whom he had exchanged smiles and a single kiss and to whom he had written friendly letters all spring. They had bumped into each other in the Tervaniemi park, and he had been delighted to see her again, and the young lady, too, had greeted him happily, and when he cheerfully asked for her news, the lady exclaimed that she had got married and proudly held out her hand to show her ring. He had congratulated her. They had wished each other all the best.

He did not speak of the matter in Viipuri, and he did not speak of it in Valencia or in Hull or in the Arctic Sea either, but the captain’s mate may have sensed something, for he was still enquiring as they arrived in the harbour at Archangel whether the girls of Viipuri had treated him badly, since his countenance was so grave; did the boss have unfinished business in Viipuri?

*

At cadet school they, the future captains and mates, had been forbidden to make friends with their crew and with each other, but the mate of the Brave II, a giant from Kokkola, a metre and a half of solid wood, had not heard this instruction. He made friends with everyone and asked after all their news and talked about it as if it was common knowledge.

Of the mate’s own business, Huurna knew only that he longed for the forests, to wander in the woodlands and kick the moose-droppings on the game trails. The mate considered the sea dull, more boring than a Liminka meadow; you could tramp across a field, but at sea blue waves rolled from one side of the world to the other and a man was trapped between them. The mate said that he had gone to sea for the simple reason that he believed what the priests said: he would end up in hell, and that place sounded so boring to him that he decided to sin in all the harbours of this world.

The mate had a foul mouth. That amused Huurna, but since he himself didn’t have the same gift for language every official-sounding sentence he uttered sounded as if he were criticising the mate. This conversational inequality didn’t bother the mate in the least: straight-talking people have an amazing capacity not to mind about such things. That is, of course, what makes them straight-talking.

Huurna remembered particularly the mate’s answer to all the men who complained about some misfortune or hurt that had befallen them: ‘A man always has something, if his tooth doesn’t hurt, he has a hard dick.’

*

The town of Archangel was so far from the world that their own familiar ship appeared, in its quiet harbour, quite especially familiar. His crew, too, seemed to Huurna his own, and familiar, and many times he found himself wishing to talk to his men about their lives and about his own, but his attempts flagged at the first formal greeting. Among themselves, the men appeared to talk about everything, home-sickness and pubs and liquor and cunt; there is no bashfulness aboard ship, and when you reach harbour you don’t go ashore to listen to a piano concerto with a bunch of roses in your hand.

Just as eating salted herring for days on end gives you a thirst, Huurna developed a strong desire to talk as if to a close friend, and in one of these moments of uncontrollable loneliness he went and revealed everything to the mate from Kokkola, his longing and his despair and his disappointment in Viipuri. The mate listened to him in silence and then rushed to his cabin, returning soon, with a conspiratorial air, to offer him his collection of pornographic postcards. The mate said he could borrow them for as long as he wanted to.

When, later, alone and unhurried, he leafed through the mate’s collection, Huurna was forced to admit that in some sense these pictures really did connect with his misery, and lightened it, even if only for a moment.

*

On the eighth of October the English came into harbour and warned that no one who intended to set sail for the open sea had ever lingered in Archangel so long into the autumn.

Huurna began to hurry the gathering of cargo, but no so much that he didn’t leave himself time to stand in salons drinking toasts, and after one of these parties he proposed.

The woman was from a Karelian family; under her colourful skirt Huurna could glimpse her light, slim calves, and he grasped the opportunity to do so as they walked along the peculiar wooden pavements of the town. One one of these walks, by happy coincidence, they spotted a bride and groom, and Huurna was prompted to try a spot of repartee. He pointed to the pair and said that they could also, perhaps, do something like it.

The following day, on a rising tide, Huurna ordered the lines to be released. His cough had become bad, and he drank liquor for his illness.

The snowstorm began as soon as they left Archangel harbour and their tug-boat. They were on the Arctic Sea on a voyage across the North Sea, but first they should have navigated the reefs of the White Sea.

In the narrow channel, the wind turned against them. All they could see of the world was the length of the ship. Snow and damp turned to ice on the decks. On the outward journey it had been light even at night on the great northern seas, but now it was dark even in the daytime. You could see the snowstorm against the sky, but toward the prow all you could make out was your own fear.

The ship, slowly becoming blanketed in snow, the dark sea below, the grim sky above and far in front the gloom of the Arctic Sea; how cold was it possible for a person to be, at sea. But when you have set out on a journey, you must take what you can from the wind, wrestle it on board and hope that after you have survived this moment you will survive the next one too.

At the mouth of the Arctic Ocean the storm eased and the sky opened up with stars. The wind, on the other hand, intensified, and the swell surged and the ship was tossed on the waves like a child’s bark-boat. The entire crew stood on deck, holding on to whatever they could.

During his years as a deck hand, Huurna had glanced in distress in the direction of the captain, hoping that the bearded father-figure would lad them to safety, but as captain all he was able to do was glance at his ship and seek in its creaking essence some sort of guarantees of the future. When they did not seem to be forthcoming, he began merely to breathe and accepted the moment, and then the next one, and thought how fitting it was that he should disappear from the world, since nothing so extraordinary awaited him that he should not be lost in this storm.

The only valuable thing that, in his distress, that he could express in words was spring, that he should see another spring. The word held within it everything that he had no time, now, to think about, the balmy days of early April, the barn wall and the sunshine, the sky in which the clouds had space to wander, the bright air which lasted well into the evening and the free, open shores.

It was spring he thought of in the storm on the Arctic Sea. He went to his cabin and thanked his ship and the heavens and something that he quietly in his mind called spring, and slept.

*

At the age of fifteen he realised he was lucky: things would always go well for him. Later, he forgot the feeling, just as the body forgets youth, and he concluded coldly that there were no lucky people, it was just that life felt easy if you hadn’t yet left the shelter of your childhood home and had not experienced very much. Then the world noticed him, too, and he began to experience the same troubles as everyone else.

In place of his lost luck he chose superstition; he began to protect himself with charms. It was lonely work. You don’t even find safety in God if you shape your prayers only in accordance with your own desires, and he did not even have a God; he had to conjure everything, make it all good, all on his own.

In moments of the most severe exhaustion he was able, for a second, to give up his superstitions and his wishes and blissfully believe that it is as it is, but as soon as his strength returned he began once again to coax luck on to his side and hope that it would once again come rippling around him. Sometimes luck accepted his wishes, sometimes it didn’t; luck is a matter of luck.

*

He woke to a shout from the lookout and struggled through layers of dreams, dragging on a sweater and oilcloths, and went on deck. All the men were now shouting. He, too, could see that they were being approached by an unlit vessel, its pale sails looming in the darkness. The helmsman had changed course and the lookout ran to check the lamps and the men were bellowing, mouths gaping, until they all fell silent, one by one, and absolute silence reigned.

All of them stared at the iceberg, unspeaking, rooted to the spot. It seemed unnatural for something so big to be so close. Mute and noble, the iceberg drifted first towards them and then past them and disappeared, without making a single sound, back into the same darkness from which it had emerged. Huurna felt a hollow stupefaction in the pit of his stomach, as when, as a little boy, he saw from a rowing boat the bottom of the sea, another world in which you could imagine whatever you liked, your father’s body. The iceberg, too, was its own kingdom, something too big to look at, and he realised now that not everyone wanted to look at it, but hung their heads as if in exhaustion.

When the iceberg lay behind them and they were sailing southward in a steady wind, he began to think that, just as children’s innocent eyes are protected from the horrors of the world, it might be better for adults, too, not to see some of the things in this world. The Arctic Sea, all of it, seemed one of those oversized things, and more particularly, the iceberg, whose threatening form he was unable to banish from his mind. Things of a suitable size for seeing included, for him, a barrel and a horse; among smaller objects, perhaps grains of wheat and the individual snowflakes which he could now make out against the dark cloth of his coat.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

No comments for this entry yet