The life of a lonely friend

Issue 3/1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

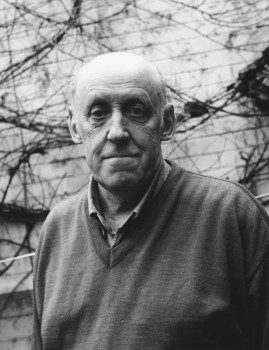

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

Extracts from Bo Carpelan‘s novel Axel, ‘a fictional memoir’ (1986). In his preface to the novel Bo explains how he ‘found’ Axel.

Preface

In the 1930s I came across the name of Axel Carpelan (1858-1919), my paternal grandfather’s brother, in Karl Ekman’s Jean Sibelius and His Work (1935). In the bibliography, the author briefly mentions quotes from letters in the book addressed to Axel Carpelan, ‘who belonged to the Master’s most intimate circle of friends, and in musical matters was his constant confidant. Sibelius commemorated their friendship by dedicating his second symphony to him’. I had never heard Axel’s name mentioned in my own family.

Many years after Karl Ekman, the original incentive for the novel about Axel arose through Erik Tawaststjerna’s biography of Sibelius, in which Axel is portrayed in the second volume (1967) of the Finnish edition, and whose life came to an end in Part IV (1978). From early 1970s onwards, I started notes for Axel’s fictional diary from to 1919. It is not known whether Axel himself ever kept a diary. I relied as muchas possible on all the available facts. These increased when I was given access to letters exchanged between Axel and Janne from the year 1900 onwards. It became the story of the hidden strength a very lonely and sick man, and of a friendship in which the give and take both sides was far greater than Axel himself could ever have imagined.

Hagalund, June 1st, 1985

Bo Carpelan

![]()

1878, Axel’s diary

15.1.

On my twentieth birthday, I remember the young Wolfgang; ‘Little Wolfgang has no time to write because he has nothing to do. He wanders up and down the room like a dog troubled by flies’. However, that dog achieved a paradise. I have learnt yet one more piece of wisdom: ‘It is my habit to treat people as I find them; that is the most rewarding in the long run’.

23.2.

With reference to the growth of the nation and its coming wealth, Father says that although they can do what they like with their forests, they should remember that even the forest has its morality, which is to go on living for the coming generation, caring for it in the way it itself cares for the landscape with its beauty; thinning in moderation is the right way. I thought about that expression ‘thinning in moderation’.

4.4.

The violin. Animal sinews forced to work, and protesting with screams.

Whitsuntide

The time of ecstasy. It isn’t expanding, but subsiding. Schubert’s Death and the Maiden, that slow movement: not ecstasy, not abandon, merely expansion, wider fields. When the sunlight has departed, there is still light. In the actual departure: light. Not the destructive flashing light, but the light of suffering and trust. Is the finale a contradiction of this utter calm? Perhaps only a confirmation of wholeness, which is acceptance of life.

18.5.

Horses like a mahogany frame round Alexander Square, relieving themselves in such quantities that no fire could break out while the volunteer fire brigade is celebrating; soot-black gentlemen and ladies crawling like fly-spots over the picture, parasols and horn music like smoke from a fire. Above that, fat, slow-moving clouds.

![]()

9.6.

Not a single star in the sky, no lodestar, however much I look. Life goes on like this, ageing me in advance. Most food is revolting to me. Letter from Axel Tamm; a lighthouse: Viktor Rydberg.

September

Yet another summer gone – where? Watched the pair of swans that return to the bay, their faithfulness, their contemptuous looks for everything outside their circle. So – be cautious with life, it wounds you. Abandon ye! Be strange; perhaps you will then manage to endure your destiny. Empty words.

24.10.

The old do not change. They are just old. The sanctity of the law, the triumph of justice, the welfare of the nation, loyalty and honesty, keeping a promise. Being punctual. Law and order. I shall dispel the last of what is dissoluble within me. But there is only one thing I cannot dispel and that is music. Then there is what is unpredictable, disorderly and passionate left, in notes and scores, and in the violin, the tormented violin.

6.11.

This will be the diary of my inner life. I shall try to avoid trivialities and not beafraid of a philosophy of my own, however childish. It will be my wailing wall, but within it shall be my cathedral. I shall build that myself. However distorted or confused it may become, like life itself.

![]()

7.10.1880

Axel comes downstairs from the attic, where he has been practising on his violin. Brother Hjalrnar meets him in the hall. Are you ill again? But Axel shakes his head. He brushes dust off himself and straightens his bow-tie in the mirror. It’s time to go. Hjalrnar thumps him on the back. Good luck, Don Juan! His features look taut and unreal in the dim light. He almost forgets his violin. Hjalmar hands it to him with a smile. Enlighten their simple souls, just as you enlighten mine. It is damp outside, and calm, twilight softening the town and giving the trees a yellow glow. He walks across Cathedral Bridge and looks up at the clock, stops and adjusts the watch he has had for his birthday. Yes, it’s time. He stops on the stairs where there’s that smell of wax polish, and draws a deep breath. Is it his, watch or his heart ticking so rapidly and delicately? Someone is practising the piano, perhaps at the Holmström’s, perhaps Greta herself, Czerny. It is she who opens the door, her great brown eyes looking softly into his. Quickly and with embarrassment he kisses her hand and bows to her mother and father, who are lined up in the drawing-room. There is a warm smell of baking and a canary is twittering in its cage. Would Herr Baron please take a seat in our simple horne? Axel clears his throat and pronounces his admiration for the picture above the Gustavian sofa, a moonlit landscape of wild forest and a waterfall, which reminds him of Marcus Larsson. Mr Holmström, a director, finds it very interesting, while Mrs Holmström tells him it is a reproduction. Miss Greta is looking at Axel, but he is looking at the canary and enquiring about its feeding habits. The maid announces that refreshments are served. On the table is a carafe of Madeira, cakes and fancy biscuits on a silver dish. He recognises it all; why does he recognise everything, why this feeling of pity and loneliness at this particular moment? He talks, converses, telling them about the manor, and it suddenly takes on exaggerated proportions. Mr Holmström talks about the increase in business in the textile trade, the future of Finland, recently opened factories, increasingly faster communications, the green gold of the forests and the power of the waterfalls, and Mrs Holmström asks whether he would not like a little more. It’s delicious, replies Axel, but he has had enough, not only that, but he is exceedingly satisfied, if that’s not saying too much. But Miss Greta’s eyes are glowing. There is something tight about Axel’s collar, or is it too hot in the room? A very beautiful shawl embroidered with roses is draped over the piano. Oh, yes, that’s right, you play the violin, Herr Baron. You’ve promised to play for us, Greta has said. For us, music is the elixir of life – and Gottfrid Holmström adds that to him Bach stands out as one of the greatest representatives of the good old music. He has recently had the pleasure of a Bach recital in the Cathedral. Yes, Bach is the cathedral-builder, Axel says, and Gottfrid Holmström finds that interesting, and how he wished many of the magnificent houses now springing up out of the ground like mushrooms could have been built by Bach and not by master-builders with no sense of style, although the building they are in now is not one of the ugliest, but has qualities not always visible if you look only at the facade and ornamentation, but more in the height and size of the rooms, and their internal proportions. Axel is shown over the apartment, the library, the study, past the bedroom, and given a quick glance into the kitchen regions, where a maid in white curtsies and disappears.

Even the corridors have parquet floors. But naturally, it is not like in a mansion in the country? But then Greta cries that Axel must be allowed to play. We’ve all been waiting for that. She runs to fetch the violin and the case to Axel. His hands trembling, he takes his beloved instrument out of its red velvet coffin. Greta asks about music, but Axel shakes his head. he plays by heart! Yes, Axel plays by heart, out of his head, which he heavily against the violin, tuning the strings, the keys squeaking, while loud barking and a door slamming can be heard from the stairs outside. They sit watching him, as if the music had already started, had materialised, taken form within him, him, Axel. Her glasses again misted over, Mrs Helene is already nodding in time with unheard music. Axel closes his eyes and the chaconne floats unsteadily and tentatively out into the drawing-room. Axel is struggling with immense shadows, piling up, occasionally dispersing, the bow heavy in his hand. Bach is mute, wandering on, blind, deaf and mute, or is it Axel standing there, a poor man playing for a coin and a cup of coffee, seeking to build a cathedral, but it becomes scarcely a dwelling house, nothing but a hovel, an outhouse, heathen thoughts flashing past Axel’s heavy head, sweat breaking out on his bare domed forehead. Surely the curtains would soon catch fire, a whirlwind would come and whip away the cakes, plates, carafes and the whole silver service into a high swirling autumnal dance, and what is his bow doing, trying to wake the dead to life? Is it trying to burn like a magician’s wand among safe objects, flowers and vases, palms and pier-glasses? Will this music perhaps create a new, an even more progressive Finland, weaving a textile from town to town, from person to person, from one piece of furniture to another? The piano stands mute with gaping lid, in which the top of Axel’s already cooling head is reflected like an eggshell in a sea of tar. Behind closed eyes, tears are gathering, even Miss Greta has tears in her eyes, and Mother Helene wipes hers discreetly away with a little lace handkerchief she has hidden in her sleeve. He finishes, almost fainting. He has done violence to the music and is in despair; but they surround him, thanking him, and Mr Holmström says: Excellent, really excellent, a great performance – but hardly a lucrative profession, eh? Pappa! cries Miss Greta. Axel has a country estate, he’s a Baron! There is an embarrassed silence during which Axel notices his headache striking home; pale, he must rest on the sofa. No, Axel must not move. The strain has been too great. Axel has drained himself! For our sake! But it is Axel who is ashamed. He has deceived them. He cannot tell them. He has betrayed the music and them, he is nothing, a shell, a clown, a man in disguise. He soon sits up and manages to stammer out that it would be better if he went home. They are filled with solicitude. He sees them with unseeing eyes, all their warmth, all that he has observed and condemned, what right has he to judge them? With their hands, they have created a home, a life, security. And he – to think that he would be able to take Greta away from this and give her – what? Axel cringes, at the last moment managing to make a joke of it. I am one of those textiles you would never approve of for sale, Mr Holmström, my fabric neither strong nor shrink-proof, and Gottfrid Holmström, with his good shiny round face, laughs, but Greta is silent, her brown eyes sorrowful as he bids farewell, as if she senses he will no longer make contact. He wanted to embrace her so very much, warm her, protect her, but he has nothing to give, nothing but a kiss on the hand. He makes his way down the stairs like a drunkard, the violin in a dead hand, the door slamming behind him like a stone coffin-lid.

Outside, the mild gas-lamps are already alight and the mist distances all footsteps and voices. He doesn’t really know where to go. There are no roads, no points of the compass, nothing but an alien city enveloped in soft mist, the river gliding unmoving past, its water almost black. The old yellow houses – he looks into them. Somewhere a room is lit up and two people are sitting at their meal, as if at holy communion. He notices it has been raining, the paving stones, glistening, and he makes his way down to the river. There is no one there, no one demanding what he cannot give. He knows that now. He can build no cathedrals, cannot even interpret their shadows, nor make the music speak. He sits down on a bench. It is cool, a wind coming through the trees and wet leaves falling round him. He opens the case and looks at the violin. It is not an expensive one, a perfectly ordinary violin, so dark, like a charred body in its coffin, with its long narrow neck and no head at all. In other hands, it would be able to sound, swing itself up into space, build cathedrals, console and please, but not in his. How mutely it lies there, nothing but a shell here on the bench by the river. Protectively, he spreads the velvet cloth embroidered with clefs in gold over the light body and closes the lid. Then he finds himself standing, he knows not how, on the bottom step, and he pushes the black craft out on to the water. For a moment it seems as he himself might fall into this darkness, this coolness, but then, kneeling, he watches it floating away, surprisingly far, until it sinks below the surface and there is nothing there, not a swirl, only the silent water streaming past and he leaning back on the wet steps, his eyes closed, feeling how cool, how lonely the world is, and feeling a great relief.

1900, Axel’s diary

10.3.

I have now written to Jean Sibelius, signing it originally with an X. Have urged him to gather his strength for an introductory overture to his Paris trip which would blow through the French spring like a storm. There must be something there, damn it! Said I hadn’t heard his First Symphony – and the next moment hear within me pines singing, the forest stepping out with darkness and light. Prescription ad libitum: allegro (mystery of the forest, sound of the shepherd’s horn, the spirit of the wilderness), adagio (magic of the summer night on the shores of the lake), scherzo (haunting) and finale (storm and the soughing in the forest, the dawn chorus, sunrise). When he has completed this Waldsymfonie, he should return to chamber music, the love of his youth. That is what I have decided with feverish agility. Deep down, my advice is a hope, a dream in which regeneration occurs, both for me and for him, for all who listen; that a new freedom would blow like a wind across countries. Finlandia! Walk restlessly through the streets, stopping to look for signs of spring, but there are few, though the mornings are lighter, as if pouring out of some secret source. Nights filled with dreams and fantasies, as if I were sure they would be fulfilled – that he answers! That one day, when I have pulled myself together into something more constructive, he will answer! But the time is not yet ripe to reveal my name. Last night I wrote a short piano piece in profound joy. In the morning, it was dead, and I had to throw it out. What is an X? The great unknown.

![]()

1907, Axel’s diary

15.1.

Today is my forty-ninth birthday. I’ve now known Janne for seven years, a seventh of my life. I have not heard from Janne, who is said to have been successful in St Petersburg. Had my warnings disturbed him?

22.2.

Janne has once again retreated into the world of inns and would-be gentlemen. I see him gesticulating, scarlet in the face, his hair standing on end, a cloud of cigar smoke round the sweaty grubby collar and cuffs, the half-empty glasses, and I remember the evening of my degradation and how thin the thread of life seemed to me. How difficult it must also be for Aino, alone with the girls at Ainola. The piano is silent. Will a clear new symphony be born out of this? Is so much decline required for something to arise?

4.3.

A huge coarse man was beating his horse, which was trying to escape, neighing, its nostrils steaming as it backed away, the cart half in a snowdrift and curses raining down. I saw the driver was drunk and desperate, that something was making him strike which had nothing whatsoever to do with the horse, and wild eyes were common to them both. I could see the stubbornness, the madness, the loneliness, despair and brutality, everything that lives its more or less concealed life around us daily. God help these people, the inarticulate and fanatics. Darkness rules them for most of the year, as well as a vague yearning for something else, warmer and more filled with love, which they cannot express. The yearning for worlds! Then they rush to choirs and amateur dramatics, where ready-made words exist; what’s left is simply curses. How should I address him! My dear good sir, please stop beating your wretched horse. You’re not making the situation any better. But with a terrible jerk on the bridle, he got the horse going, threw himself up on to the cart and set off in the slush with his whip held high. No one took the slightest notice of the situation, all hurrying on as if they’d seen nothing. Not only are we mute, but also blind and deaf.

3.4.

Have been up for a few days and can read again. Have studied Beethoven’s later sonatas, the inward-looking ones which open up space – is Janne on his way there? I await his letters, or at least a line, like the thirsty waiting for water in the desert. He must realise I am always at his side.

4.4.

Tolstoy hates music because it touches him deeply, threatening his moralistic empire with its richness. The fact that it speaks to the emotions and the irrational frightens him, and he is not entirely wrong. There is in music a power that can be abused, something that lures you towards the desperate, the divided, the nocturnal, to hell. But did he not see harmony, light and elevation in music? Music was distorted to him. He saw his own features in the mirror and confused them with those of music. His agony is palpable, as is his rage and fear of music, of sex, and of what is spontaneous.

6.4.

If I had the right of primogeniture, like Kierkegaard, I would happily give it to the porridge of childhood with its dab of butter. Yes, in spirit I am still sitting at table with Father and Mother, with brothers and sisters, aunts and Uncle Fredrik, as if unaware that I am sitting here alone.

8.4.

Still not a line from Janne. The pigeons on the window-sill toss their heads and turn their blind eyes towards me, extending their necks and making messes. There are several blank patches in the past, and I find them partly filled by these notes. What doesn’t exist here has gone.

18.4.

I cannot deny the erotic nature of male camaraderie. It has something to do with the eye’s enjoyment, and also the other senses. The ugly dilettante should not bother! Symposia of male strength, equivocal memories, exuberant friendship and loud bursts of laughter as protection against loneliness and misfortune, sunning oneself in the glow of epaulettes and orders, wealth and power, loud bursts of laughter, saunas and rituals, they all make me sick. So my contacts have been with men with ideal natures, such as a warm correspondence permits. Viktor Rydberg and Axel Tamm once, and now Cousin Tor and Janne are all close to me. With little faith, I let my meagre striving for ideals direct itself to the brilliant, to Janne, in an attempt to counteract my outward and inner poverty. The church mouse as patron! But that’s at an end. What remains? A bed, a desk, a bookcase, bundles of paper, a few chairs, a case in a cupboard, fading photographs, two with greetings taken recently of Tor and Janne. Not to forget the piano. And those heaps of paper, my only way out, apart from letters and music. Isn’t that enough?

![]()

4.9.1912

Axel arrived in Ainola one grey September day. As soon as he was in the hall, he met that special smell of wood and silence, despite the noisy girls. They were in white, their plaits flying as they opened the door, Margareta and Heidi looking expectantly up at him, Kaisa keeping in the background. Behind them was Aino, grave, gazing intently at him. He suddenly felt awkward and put down his case. Janne had met him and was now out in the garden, listening and peering up into the sky.

Axel rummaged in his coat pocket and took out the three cotton-reels he had carefully wrapped in paper. He was not very good with his hands, but he could do this, cutting grooves in the edges, rubbing paraffin wax on the sides, cutting sticks and not pulling the rubber bands too tight. He went down on his knees with the girls around him. Jerkily but sure, the little wagons rolled forwards. Aino also knelt down, looking at the wagons and the girls, but avoiding his eyes. Janne walked past them in his best shoes, a gentleman. The girls kissed him wetly on the cheeks, then disappeared. A clatter could be heard from the kitchen. Janne called to him.

In the drawing-room, everything was as before, the Gustavian suite of chairs and sofa, the white curtains, the jar in front of the stove, the beams, the tapestry, the garlands… ‘Yes, the garlands have increased,’ said Janne, following his gaze. ‘In this house they hang on the wall, though usually they are put on a burial mound.’ Janne’s voice was harsh; there was a tension in the air which Axel could feel physically, and he grew warm. He looked at Janne. There was something cold, absent-minded, averted. Aino disappeared out into the kitchen. Suddenly Janne changed, led him out on to the veranda, smiling and close: ‘My dear friend! You’ve no idea how welcome you are. Come and take a look at my view.’

They stood looking out over the fields, the pines swathed in a faint mist, the air quite calm. For a moment, they stood in silence, then Janne said: ‘Aino is upset about Favén’s portrait. She thinks I look like a butcher – a drunken butcher. Maybe she’s right. Maybe the portrait will kill her love for me.’ He drummed his fingers on the wooden rail, the first movement of the third symphony, rapidly, then suddenly spoke: ‘I can’t create! I’m stuck. They all – they all make such demands. Except you.’

Axel looked at him and he at Axel. ‘The true picture can’t be wiped out by a false one,’ said Axel. ‘What do you know about it being false?’ replied Janne. ‘Perhaps it’s true. I’m no Sunday School teacher. You know that as well as Aino does. Heaven and hell – I strive for both. And am – lonely. Do you see?’ He turned away and pointed up towards the mild sky. ‘See, it’s almost empty. No birds – I haven’t heard wingbeats for an eternity. Am I going deaf? Like Beethoven? What do you think?’

‘I think you should go to a doctor,’ said Axel. ‘If you’re worried. As far as Favén’s portrait is concerned, I’ll speak to Aino. The fact that you can’t work is temporary, you know that. The only demands you should consider is that you put trust in yourself.’

A mild breeze arose and the clouds started lifting. Axel felt slightly dizzy and put his hand to his forehead. He also had something to confide in to Janne: that he had been very ill, that he had been living in self-contempt and impotence and had come to the conclusion that long sequences of time in his life no longer had any chronology. He forgot, coming events experienced with painful force shifting into the past, and more and more frequently he found himself outside himself, feeling guilt – that word which ought to be eliminated, from the Bible, from faith, from the lives of human beings. Guilt – since childhood: guilt.

For a moment, they stood in silence listening to the wind in the trees. ‘Yes, I have also felt guilt,’ said Janne. ‘Over Aino, the children, my trips to town- over the years I’ve felt a greater and greater need for solitude, and nowadays I seem to be indifferent to a great deal. Nothing left but music. Creation. Being an interpreter – that sometimes is the greatest happiness, the greatest torment.’

‘I’ve listened to it,’ said Axel. ‘It’s there, in everything you create, that yearning. Look, the sun’s breaking through, like in Lemminkäinen in Tuonela! Have you ever thought about those two simple words lonely and common – maybe loneliness is what we have most in common – not just you and me. Everyone.’

‘Christ, how philosophical we’re getting,’ said Janne. ‘Listen to the ducks flying as if for dear life! There!’

They gazed after the skein of ducks as they fled over the treetops in terror. Aino came out to them and told them about the garden, what she had done. Axel asked and Janne contributed with grunts. They went back in and sat in the library. Janne had put on weight, even more weight, his chin above the brilliant white collar glistening, his hair carefully brushed – not at all like the Gallén portrait hanging in the drawing-room, no longer the wild radical. He had spread, the deep lines between his eyebrows like calluses, those eyes that could suddenly lose themselves in the distance.

Axel felt strangely tormented, as if he had imposed himself. He brought the conversation round to music, the few concerts he had been to, the near unattainable simplicity, in contrast to the mechanical Germanic apparatus Wagner did his best to construct – ‘that brawling gnome from Saxony with his rumbling talent and bad character’. Axel was quoting Thomas Mann. Janne laughed, then grew serious. Anyone could probably acquire that bad character. He glanced quickly at Aino. Axel nodded. ‘Money that was never sufficient! Because you were to have things as you liked them, making the grand gesture rather too often,’ said Aino. He admitted that – yes. And how much of Axel’s money he had wasted – just because he wanted to oblige- and enjoy it himself! A petty bourgeois trait perhaps Axel didn’t understand?

Axel understood. But it wasn’t his money Janne wasted – if that word could be used. He himself had no money, had long been without and got used to it. He often felt socially degraded. All that mattered was not to degrade yourself, deep down within you. If he understood Janne correctly, what was deep down within him was the Fourth Symphony and Voces. ‘Go the inner way – how many thanks does one get for that?’ asked Janne. ‘Do I even know myself? Maybe I am a butcher, just as Favén painted me. I drink, live and will perhaps grow as old as that rya hanging there on the wall.’

Aino got up and went out. Axel looked at the rya; ‘Lemo W 1841’, it said on it. ‘It’s from my home district,’ said Axel. ‘Masku, Lemu, Askais, Merimasku notes from home. It’s only seventy-one years old.’ He could hear his own voice, listening for Aino, but there was silence from there. ‘It’s old and worn, like me,’ said Janne. ‘You!’ said Axel. ‘Talking about old and worn, I’m so tired after the journey, I must go and rest for a while – we’ll talk business later. And if you would play for me – I’d be grateful.’

Janne came with him up the stairs. The room was cool, the window slightly open. They had remembered that, his habit. He lay down and closed his eyes. He wished himself elsewhere. He could hear children’s bright voices, then someone shushing them. He tried to conjure up Rakel’s face, there in that distant room, in the entrance porch, trying to listen to her voice. Her face shifted and became Aino’s face. He wanted to run to her, but it was a child, the scent of phlox and women in white disappearing in the mist.

Axel woke from Aino opening the door. ‘Dinner is served,’ she said. ‘If you want a wash, the water-jug is there.’ She took a few steps into the room. ‘You are Janne’s and my best friend, Axel, and we’re so pleased to see you, but things have been difficult lately – I’m sure you’ve noticed. And Favén’s portrait – I detest it! That’s not Janne. It’s the other one that I don’t want to know.’

‘We’re often separate people. It’s night and day, and perhaps they need each other,’ said Axel, ‘but I, too – also find the portrait alien – it’s just surface, the most superficial of surfaces.’

He had wished to say so much more, but was unable to. He had wanted to take her hand. But she simply nodded, looking into his eyes so gravely, her own full of gentleness and melancholy, and he felt inadequate. She turned and went downstairs. He washed hurriedly, dried himself on the towel, looking with unseeing eyes at the stranger with a rigid face, then closing the door carefully behind him and listening: happy voices could be heard from the dining-room. He went on down.

He was sitting on Aino’s left, the girls next, then Janne, who tossed the salad. That was his ritual, carried out with the gestures of a head waiter. When Janne sat down, Axel saw how big he had become, the table-napkin glowing beneath his chin, his complexion flushed, perspiration appearing on his forehead. They ate long and heartily. Janne told stories and the wine went to Axel’s head. He was sitting as if among his own family, as if he had one, tossing remarks back and forth. Was this where this ability came from, this swiftness? September light and smells of food, the cook coming and going, knives and forks raised and lowered, glasses glimmering, the dark walls, Aino grave and Janne hunched over his plate – did Janne see him at all? There was something mute there, something dissipated, spots on his cuffs, a veil of wine, of grease, his lips moist, his stomach propped against the edge of the table. It was Favén’s model sitting there!

A lump rose in his throat and he could hear an indistinct murmur getting louder. He leapt up and there was Janne’s wrist with raised fork. He seized it: ‘Not another potato! D’you hear! You’ve got fat! Fat!’ He looked into Janne’s eyes and saw the glint, something quite alien, scornful. Janne got up quickly, shaking off Axel’s hand. ‘No one says things like that to me in my own house! No one!’ he cried. ‘No one!’

Axel took a few stumbling steps back, knocking over his chair, a yawning silence descending on the table. He saw the whole monument, the layers of fat, the music hidden somewhere far inside, the face flushed and coarse, he himself burning or frozen to ice. He flung down his table-napkin and headed for the hall, started half-running, rushing out half-blinded, his heart thumping like fist-blows on his thin chest. He was dying! He felt it. He started walking aimlessly on in towards the forest, towards rays of sunlight, birds fleeing, people running up to him, Aino and the girls. They were pulling at him, seizing his arms, and he stopped, exhausted. Aino was holding on to his arms and appealing to him, quickly, stumbling over her words: he wasn’t to go away, he mustn’t desert them, he was needed, and she didn’t know what she would do if he broke with Janne, Janne was in a highly-strung state, desperate – Axel mustn’t become that. He must come back. Janne had meant no harm! Axel raised his eyes and saw her anguish. He was the one who had offended, he realised that and he had no right to say such things in Janne’s house, but he had been unable to endure the sight – from the moment he had arrived – it had been beyond his ability to cope.

Aino took his arm and the girls followed them as if in a funeral procession. The Master was standing lowering in the doorway. He held out his arms and they embraced, with no words, just standing there swaying, Axel almost disappearing in Janne’s arms, agitated and tearful. He sank down on to his chair and wiped his forehead with his napkin. He didn’t understand what was wrong with him, what had driven him. The table, the people, the unreal and hurtful light, and yet he felt a painful relief over the way things had gone, that some of what had been burdening him had found expression. They all crowded round him noisily, wishing him well. Janne laughed and asked whether in Axel’s opinion he dared take some dessert. ‘I’ve told you you could live considerably more austerely in many respects,’ said Aino. Wasn’t the Fourth Symphony austere enough? That he could be so ravenously hungry after the meagre meal? He had something to show Axel; the Fifth.

They left the table and he followed Janne to the piano. Janne sat down, his face now stern and closed. Out of his body, out of his fingers, out of those closed eyes, out of the unknown it came, pouring over him, the new, expansive, once again something new, a greater freedom, a wealth, a – joy. It was sculptural – yes, not pictures, but blocks Janne was working on, floating about between the timbered walls, seeking their way out through the open door to the veranda where dusk was falling, the late sunlight like honey on the walls, like resin or amber, an eternal soft dry aroma.

The landscape outside fell still. Janne stopped playing, and with his arm round Aino and Axel, they went into the library. Aino excused herself and disappeared, walking slightly bowed, a bird. The remaining two sat in silence, listening to the silence which was never truly silent; there were voices, the wind blowing, birdsong. It was calm here, the focus Janne needed – Axel himself had none, he said. A rented room. Did Janne know how fortunate he was? And whom he had at his side?

Of course he knew. Soon he would be ready to embrace everything, soon, but not yet. There was so much unrest, not only in the times, but within himself, and a torment he could not express, a grief he was trying to overcome. ‘Yes, sooner or later, there’s always water between the shores,’ said Axel. ‘That’s where Tuonela’s swan is, and our grief over how quickly traces of us are wiped out, and so much is chance. “Dark is the black bird’s heart – even darker my own” as the song says. But Janne, you’re heading for your Fifth Symphony! Your dark moments swiftly become light ones, and out of darkness you find strength. Longing and departure – and again longing home – that’s what you constantly appear to be saying.’

Janne sat there in silence. Axel saw in front of him the morning mist above the silent water in Lemminkäinen’s Tuonela, a breeze making the water glimmer like liquid pewter, but when he looked out of the window, all he could see was dark treetops. The music, that was somewhere else, not here, not in what he said, not in the silence. It was Janne’s property, all else excuses. He had forgotten something. He gripped the arm of the chair convulsively, hoping Janne would notice nothing. Wasn’t all this to conceal the loneliness, the poverty of creative life – to conceal his intermittent loss of memory, his crippled spirit, his fears. Even now, when he wanted to reach Janne, be open towards him, something false crept in. He fell silent, feeling utterly empty. Janne got up and went over to the window. Axel took out his watch and turned it to the light from the window. It was midnight. Time to turn in. ‘I’m going to bed,’ he said. ‘I’ve talked too much. Goodnight.’

He went over to the stairs, turned round, scarcely able to make out the dark figure. ‘I’m glad you came,’ said Janne. ‘Your friendship means a great deal to both Aino and me. And to my music. You hear what I hear. That’s more than enough.’

Axel almost stumbled on the stairs, his heart thumping violently, and soaked with sweat, he made his way to his room, sat down on the bed and closed his eyes. Blurred images flickered past, fragments of words, ‘music is not everything’, ‘spiritually retarded’, ‘the biped animal’, words without meaning. The wind blew through the birch outside; autumn had come. What was he doing here, alone on the edge of a bed, a grain of dust, people breathing all round him? Slowly he lay down, fully clad. The quilt felt cool. Were they, like him, lying there listening? To what? There was nothing there, nothing to listen to. He turned slowly on to his side and closed his eyes. Was he sleeping, or holding vigil? He lay with his legs drawn up, like a child, or, an insect.

1919, Axel’s diary

1919, Axel’s diary

8.1.

Janne sent the Luonnotar as a New Year gift – a consolation present. Apart from resources of voice, it demands of the singer intuition about nature and a mystical imagination – Lilli Lehmann could have sung it. Wish that Janne could publish Kullervo. Have read a great deal in my impatience to know everything – unnatural in a sixty-one year-old, but heralds the early oncoming of death. The wide wings of the cold-eyed swan. As if it gave strength.

24.2.

Janne sees quite clearly that the first movement of the Fifth Symphony is ‘one of the best I’ve composed’. So that movement is saved.

27.2.

Mrs A. Lindberg wants to let my room for the summer – don’t know whether I’ll get back my old room in Nådendal. Written to Janne about his smoking- early hardening of the arteries comes from that. Read Vretblad’s Concert Life in Stockholm in the Eighteenth Century. It’s icy cold.

15.3.

When will the swans depart, when will they return? I’ll write to Janne.

Translated by Joan Tate

Tags: classics

No comments for this entry yet