Author: Kai Laitinen

On not translating Volter Kilpi

Issue 1/1996 | Archives online, Authors, Reviews

Volter Kilpi’s classic novel Alastalon salissa (‘In Alastalo’s parlour’, 1933) has a reputation as a ‘difficult’ book. A Swedish translation is finally ready, but no one has ever succeeded in translating the work into English. Books from Finland decided to commission an extract – and had to admit defeat

‘Volter Kilpi is no good for people with weak lungs,’ said the poet Lauri Viita, some time toward the end of the 1940s. ‘Reading him, you get out of breath straight away.’ Kilpi’s major work, Alastalon salissa (‘In Alastalo’s parlour’) will take even an experienced reader two weeks, wrote another, older poet, Aaro Hellaakoski, in a 1937 essay.

Both were right. If one begins to read Volter Kilpi’s extended novel Alastalon salissa (1933) in the spirit of an entertainment or a detective novel, one soon tires. One can negotiate the slow tempo of its text, its long, curlicued sentences and wildly original vocabulary only by applying the brakes and pausing from time to time. For myself, I have found the twoweek reading period prescribed by Hellaakoski about right. Kilpi is a demanding writer: every word must be read, the path of each sentence followed to the end. More…

A writer and his conscience

Issue 1/1993 | Archives online, Authors

In the autumn of 1891 the brilliant young law graduate Arvid Järnefelt, 30, was just embarking on his pupillage in the lower courts of justice when he suddenly changed his mind. He broke off his promising career in the middle of a legal term, explaining that he could not sit in judgment over anyone. Behind his decision was his encounter with the work of Leo Tolstoy. After reading Tolstoy’s What is my faith? and The Spirit of Christianity, Järnefelt was stopped short by a sentence from the Sermon on the Mount: ‘Judge not, that ye may not be judged.’ He wished to obey the command to the letter, and changed the direction of his life, immediately and radically. First he learned the skills of smith and shoe-maker in order to earn himself a living by the work of his own hands; later he bought a small piece of land, and became a farmer. More…

Builder of words

Issue 4/1988 | Archives online, Authors

The poet Lauri Viita (1916–1965) was a master of rhyme and rhythm, a linguistic sorcerer who, for that reason, has been little translated into other languages. He also gave his home of Pispala, a suburb of Tampere, a lasting place in Finnish literature with his novel Moreeni (‘Moraine’)

In the course of a couple of years after the Second World War Finnish poetry altered unrecognisably. The old post-symbolic poetry with its artful end rhymes suddenly seemed old-fashioned and its diction hackneyed. The new poets, Paavo Haavikko foremost among them, wrote a great variety of texts, abandoning fixed rhythms and end rhymes. The circle of adherents to the ‘old’ poetry seemed to be restricted to poets who had begun their careers before the war; almost all the younger writers followed the new direction.

There was, nevertheless, one exception: Lauri Viita (1916–1965). Making his first appearance in Finnish poetry in 1947 with a volume entitled Betonimylläri (‘Concrete mixer’), he was able to breathe new life into many of the stylistic forms of traditional poetry: he used end rhymes in a way that had never been seen before and brought into his poems words that had previously been avoided; he demonstrated himself to be a master of rhythm, with a totally individual ability to paint with vowels and hammer home combinations of consonants to their greatest effect; he brought to poetry new attitudes and subjects, above all the fresh, unself-conscious rhythms of speech. More…

Life and sun: the writer and his time

Issue 2/1988 | Archives online, Authors

Frans Emil Sillanpää (1888–1964), one of Finland’s most read authors, was born in the parish of Hämeenkyrö, amid the farmlands of Western Finland. In forty years he published twenty works: novels and short stories. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1939; his works have been translated into more than two dozen languages. His centenary year produced exhibitions, lectures, publications, readings, radio and stage plays, radio and television programmes.

Sillanpää, biologist, realist and mystic: literary scholars in Finland have always disputed about his qualities as an author. Depth psychology, D.H. Lawrence, nature lyricism, Henri Bergson, deep-rooted peasant philosophy, intertextuality, life worship – all can be found in Sillanpää’s work. Modern or old fashioned, a regional writer, or an internationally renowned Nobel Prize author?

From time to time the world press prints survey assessments, rather like score cards, of the Nobel literature prizes. They are usually intended to rap the knuckles of the Swedish Academy, but at the same time they attach a value on the international literary market to the recipients of the awards.

Finland’s only Nobel laureate, F.E. Sillanpää, who received his prize in 1939, seems at present to rate low internationally. Writers awarded the prize at around the same time seem, it is true, to have suffered a similar fate: his predecessor Pearl S. Buck, and his post-war successors Johannes V. Jensen and Gabriela Mistral, although the latter do have their own purely local importance. There are some literary histories that allow Sillanpää just a couple of lines along with other regionalists and describers of peasant life, such as the Pole Władysław Reymont, Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz of Switzerland, and Jean Giono of France. More…

A poet’s perspective

Issue 4/1986 | Archives online, Authors, Reviews

Aila Meriluoto. Photo: Pertti Nisonen

When Aila Meriluoto burst on to the world of Finnish poetry 40 years ago in the autumn of 1946 she was at once hailed as a youthful prodigy. Praised lavishly by the leading critics, the 22-year-old poet’s first collection, Lasimaalaus, sold in phenomenal numbers: in a couple of years it went through eight editions, or 25,000 copies, which in Finland is still a record figure. Today total sales are well over 30,000.

Two poems attracted particular attention. One was Kivinen Jumala (‘God of stone’), a poem of defiance unleashed by the experience of wartime bombing, in which God is portrayed as having changed into a stone statue, and people as having hardened correspondingly. It was the first reaction of the younger generation to the war – abusive, strong and inevitable, the proclamation of the death of the kind, just God.

The other central poem of the collection was Lasimaalaus (‘Stained glass’) from which the collection took its name: a taut post-symbolist vision and a dazzling synthesis of the oneness of the world. Baudelaire, master of correspondances, might well have been satisfied with it. More…

The man and his work

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Authors

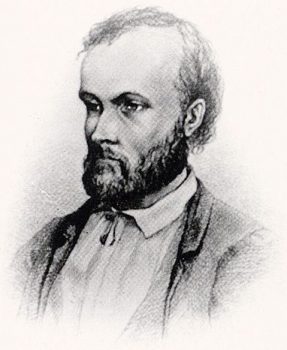

Aleksis Kivi. Drawn in 1873 almost certainly by Albert Edelfelt (1854–1905).

Aleksis Kivi’s Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers, English translation 1929), is the best known and the most beloved in Finland. Its sentences have become part and parcel of the common tongue. Its events are often cited as historical happenings, its characters and their vicissitudes are now permanent national property just as the characters of Shakespeare are for the English, those of Molière for the French, or those of Cervantes for the Spaniards.

Aleksis Kivi’s life (1834–1872) is filled with paradoxes and unanswered questions. How could a village tailor’s son who has acquired only a little learning at home and who managed to graduate from secondary school, after many efforts, only at the age of 23, became an author of the first rank? How could a man who travelled within a radius of only a few dozen miles during his life know the Finnish landscape and the Finnish mind so thoroughly that his novel even today, mutatis mutandis, conveys a true picture of an entire nation? How could he free himself from the spirit and the idealised conception of the art of his own day so completely as to be able to write books sharply at variance with the other literary works of the same era, in which he followed his own path and found fully independent artistic solutions? And how could a book which is, practically speaking, the first Finnish-language novel and which thus springs up as a unique phenomenon from an inadequately cultivated linguistic soil, reach such heights as to become the supreme achievement of all Finnish literature? The enigmatic quality of Kivi’s character is further enhanced by the fact that there exists only one authentic portrait of him, drawn when he already lay dead; that the original manuscript of Seitsemän veljestä is not extant; and that of his letters, only about seventy have been preserved, some only brief notes and most of them dealing with financial arrangements. More…

On Bo Carpelan

Issue 3/1977 | Archives online, Authors

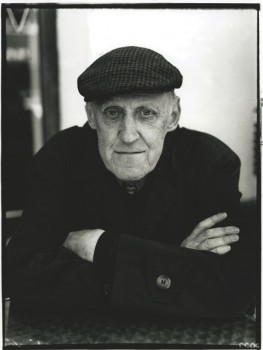

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Ulla Montan

For a small country Finland is richly endowed with poets. Of particular interest, in view of the smallness of the Finland-Swedish population (about 7% of the total), is the number of poets who speak and write Swedish as their first language and consistently produce work of outstanding quality. International recognition of the work of one of these poets came earlier this year with the award of the Nordic Council Literary Prize to Bo Carpelan.

Carpelan’s first volume of verse, Som en dunkel värme (‘Like a dark warmth’) appeared in 1946. Since then he has brought out a further ten volumes of poetry and six prose works (all published by Schildt, Helsinki). It would be difficult, and probably premature, to attempt any detailed analysis of the fusion of influences and inspiration that have come together in Carpelan’s poetry. It is clear, however, that his early work has points of contact with the Finland-Swedish modernism of the 1920s and that he followed with particular interest the 40-talists, a group of Swedish poets active in the 1940s: the influence of their heavy, profuse imagery can be discerned in his early collections.

Critics identify two main periods in Carpelan’s poetry. The first of these is represented by his first volume and by Du mörka överlevande (‘You dark survivor’, 1947), Variationer (‘Variations’, 1950), Minus sju (‘Minus seven’, 1952) and Objekt för ord (‘Objects for words’, 1956). The second period begins with the collection Landskapets förvandlingar (‘The changing landscape’, 1957) and was followed by Den svala dagen (‘The cool day’, 1961), 73 dikter (’73 poems’, 1966), Gården (The courtyard’, 1969), Källan (‘The spring’, 1973) and most recently by I de mörka rummen, i de ljusa (‘In the dark rooms, in the bright ones’, 1976). In all his poetry Carpelan sees life as a mystery, but his approach to this mystery changes and develops. In his earlier works his language is deft, yet at the same time private and intimate, later it becomes sharp and simple. More…

-

About the author

Kai Laitinen (1924–2013) was a literary critic, journalist, author and professor of Finnish literature at Helsinki University. In early 1950s he was the editor of the new literary journal Parnasso. Among his publications are literary history books, essays and a memoir. Laitinen was also the Editor-in-Chief of Books from Finland from 1976 to 1989.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.