Archive for June, 1987

Three short stories

Issue 2/1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

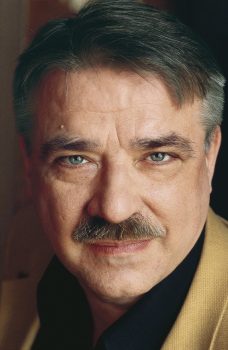

from Väärinkäsityksiä (‘Misconceptions’). Interview by Markku Huotari

Love

Kaija couldn’t understand why she felt like laughing all the time.

‘As for me, what I stand for is good old-fashioned courtesy,’ he pointed out.

He’d got a soft, low, caressing voice. He rested his hand on Kaija’s shoulder. They’d got that far already. Kaija had decided to say yes, even though he hadn’t suggested anything yet. She was beginning to picture luxurious rooms, gourmet dishes, expensive drinks, and tender, passionate lovemaking.

‘Socially I’m a radical,’ he said. ‘Culturally a liberal, but in personal things an unshakeable conservative. A woman, in my view, is to be respected – I don’t consider that damaging to her independence. Too often, in today’s world, equality’s used to justify what are quite simply bad manners.’ More…

A small lie

Issue 2/1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Pieni valhe (‘A small lie’). Introduction by Marianne Bargum

The white cat had started to hate her.

Only half a year ago, Marja remembered, it had been playing with the hems of her robe, while she had passed the morning reading and drinking coffee. Right now it was staring relentlessly at her from the bookcase where it was ensconced: out of reach, she thought. Its stare was green and mean. At night it attacked her ankles; it lurked in the crevices of the apartment and when it heard her approaching steps it leapt past her, screaming, and crossed the room to the curtains or the table. The curtains fell, books crashed to the floor, the cat stared with its eyes opened wide, the pupils like narrow slits. She would lock the cat into the other room for the night, hear it mew and feel the door with its paws; she fell asleep only after the cat had calmed down. When she approached it during the day, stroked it and called its name, it looked at her, motionless, as if it had seen and known everything, and then she withdrew her hand, backed off, started behaving as if there wasn’t even a cat in the apartment. More…

Poems, poèmes

Issue 2/1987 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Mies joka rakasti vaimoaan liikaa (‘The man who loved his wife too much’, 1979 and Vaikka on kesä (‘Although it’s summer’, 1983). Interview by Markku Huotari

Look at this epitaph with whiskers.

Threw herself so gladly into my troubles, sometimes she seemed to be bearing, properly, my burdens.

A dog called Julia. Combining

July and Yuletide.

Often thought of putting her down, so she wouldn’t need to die.

Smash her skull or break her neck

with my own hands, to stop her mourning her premature death.

Which still seems to be delaying.

She puts her four paws gently down, one at a time. So the Lord won’t hear her still about

and whisk her away.

Two years ago, she steps on some glass, her toe sticks out, a tendon’s cut.

She looks at me. Believe it or not,

I’m grieved by little Julia’s lot: for a second

I think the blood’s dripping from my own heart. More…

Poems

Issue 2/1987 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Vattenhjulet (‘The water-wheel’, 1986). Introduction by Thomas Warburton

Together with time

One day the door to my room closed

and fate said to me: be still.

It was then that I discovered time.

It had lain hidden beneath a lid

of events and hasty decisions.

It was then that I raised the lid.

So strange! There time lay

completely unused, completely itself

smooth and fresh, as if resting.

I looked at time with reverence.

I saw myself new, I sank into

a miraculous eventlessness

together with time

listened to myself living:

a barely perceptible murmur.

The water-wheel

The old horse plods heavily with blinkered eyes the wheel turns slowly and inexorably creating time, a thing that is not visible that is really nothing with the right to kill.