Archive for November, 2011

Government Prize for Translation 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

María Martzoúkou. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

The Finnish Government Prize for Translation of Finnish Literature of 2011 – worth € 10,000 – was awarded to the Greek translator and linguist María Martzoúkou.

Martzoúkou (born 1958), who lives in Athens, where she works for the Finnish Institute, has studied Finnish language and literature as well as ancient Greek at the Helsinki University, where she has also taught modern Greek. She was the first Greek translator to publish translations of the Finnish epic, the Kalevala: the first edition, containing ten runes, appeared in 1992, the second, containing ten more, in 2004.

‘Saarikoski was the beginning,’ she says; she became interested in modern Finnish poetry, in particular in the poems of Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). As Saarikoski also translated Greek literature into Finnish, Martzoúkou found herself doubly interested in his works.

Later she has translated poetry by, among others, Tua Forsström, Paavo Haavikko, Riina Katajavuori, Arto Melleri, Annukka Peura, Pentti Saaritsa, Kirsti Simonsuuri and Caj Westerberg.

Among the Finnish novelists Martzoúkou has translated are Mika Waltari (five novels; the sixth, Turms kuolematon, The Etruscan, is in the printing press), Väinö Linna (Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier) and Sofi Oksanen (Puhdistus, Purge).

María Martzoúkou received her award in Helsinki on 22 November from the minister of culture and sports, Paavo Arhinmäki. Thanking Martzoúkou for the work she has done for Finnish fiction, he pointed out that The Finnish Institute in Athens will soon publish a book entitled Kreikka ja Suomen talvisota (‘Greece and the Finnish Winter War’), a study of the relations of Finland and Greece and the news of the Winter War (1939–1940) in the Greek press, and it contains articles by Martzoúkou.

The prize has been awarded – now for the 37th time – by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation from FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

Kari-Paavo Kokki: Tuolit, sohvat ja jakkarat. Renessanssista 1920-luvulle [Chairs, sofas and stools. From the renaissance to the 1920s]

24 November 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Tuolit, sohvat ja jakkarat. Renessanssista 1920-luvulle

Tuolit, sohvat ja jakkarat. Renessanssista 1920-luvulle

[Chairs, sofas and stools. From the renaissance to the 1920s]

Photographs: Katja Hagelstam

Helsinki: Otava, 2011. 175 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-23415-9

€56, hardback

Could it be that chairs are the most important pieces of furniture in our daily lives? The history of furniture in Finland – not much has survived from earlier than late 16th century – is made up of Swedish, Russian and Finnish parts. Furniture-making in the Kingdom of Sweden, of which Finland formed a part until 1809, was modelled on European trends, and that was also the case in St Petersburg – which is close to Finland – during the period when Finland became a Russian-governed Grand Duchy (1809–1917). Finnish peasant furniture has always been of high quality, despite often harsh circumstances. Finnish furniture-makers adapted both Swedish and Russian styles; for example, Empire (in England, Regency) and Biedermeier chairs were either of the Russian or the Swedish type. Gustavian furniture (c. 1775–1810), from the period of King Gustav III, was popular and abundant, and in the past decades the style has become extremely favoured by collectors. Detailed, beautiful photography in this book supports the concise, informative text. Kari-Paavo Kokki, director of Heinola City Museum, is an antiques specialist.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2011

24 November 2011 | In the news

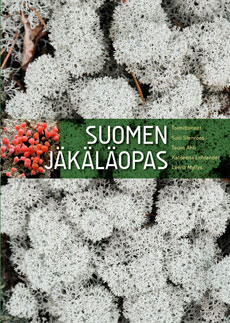

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

‘Scientific, aesthetic, timely: the work is all of these. A work of non-fiction can be both precisely factual and emotional, full of both information and soul. A good non-fiction book will surprise. I did not expect to be enthused by lichens, their variety and colours,’ declared Professor Alf Reen in announcing the winner of this year’s Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction on 17 November.

The winning work is Suomen jäkäläopas (‘Guidebook of lichens in Finland’), edited by Soili Stenroos & Teuvo Ahti & Katileena Lohtander & Leena Myllys (The Botanical Museum / The Finnish Museum of Natural History). The prize is worth €30,000.

The other works on the shortlist of six were the following: Kustaa III ja suuri merisota. Taistelut Suomenlahdella 1788–1790 [(‘Gustav III and the great sea war. Battles in the Gulf of Finland 1788–1790’, John Nurminen Foundation), written by Raoul Johnsson, with an editorial board consisting of Maria Grönroos & Ilkka Karttunen &Tommi Jokivaara & Juhani Kaskeala & Erik Båsk; Unihiekkaa etsimässä. Ratkaisuja vauvan ja taaperon unipulmiin (‘In search of the sandman. Solutions to babies’ and toddlers’ sleep problems’ ) by Anna Keski-Rahkonen & Minna Nalbantoglu (Duodecim); Operaatio Hokki. Päämajan vaiettu kaukopartio (‘Operation Hokki. Headquarters’ silenced long-distance patrol’), an account of a long-distance patrol strike in eastern Karelia during the Continuation War in 1944, by Mikko Porvali (Atena); Trotski (‘Trotsky’, Gummerus; biography) by Christer Pursiainen; and Lintukuvauksen käsikirja (‘Handbook of bird photography’) by Markus Varesvuo & Jari Peltomäki & Bence Máté (Docendo).

Turd i’ your teeth

24 November 2011 | This 'n' that

Swearwords: universal language? Picture: Wikimedia

The title is a phrase by Shakespeare’s contemporary Ben Jonson, used in his plays.

In Japanese, swearwords are unknown. The worst thing you can say to a member of the African Xoxa tribe is ‘hlebeshako’, which roughly translates as ‘your mother’s ears’. ‘Swearing involves one or more of the following: filth, the forbidden and the sacred,’ says the American-born journalist and author Bill Bryson in his book Mother Tongue. The Story of the English Language (1990). It is a very entertaining and enlightening work full of interesting facts and peculiarities, many of them about a languages other than English.

There is one faulty reference to the Finnish language, though, and we do wonder how it has got into the book:

‘The Finns, lacking the sort of words you need to describe your feelings when you stub your toe getting up to answer a wrong number at 2.00 a.m., rather oddly adopted the word ravintolassa. It means “in the restaurant”.’ (p. 210)

Indeed it does, and definitely we never did. Adopt, that is. We’ve never ever heard anyone substituting a solid swearword – and there is no lack of sustainable, onomatopoeically effective (lots of r’s) examples in the Finnish language – for ‘ravintolassa’. Darn! Any Finn (prone to cursing) would say PERRRKELE, for example.

Someone, we fear, has been having Mr Bryson on.

A thankless task?

24 November 2011 | Letter from the Editors

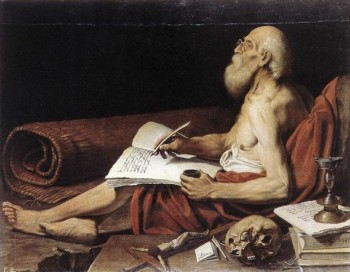

Translator at work: St Jerome, translator of the Latin Bible in the late 4th century, is the patron saint of translators and librarians. Leonello Spada's 1610s painting, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome. Picture: Wikimedia

Why translate, asked the late Herbert Lomas thirty years ago in an issue of Books from Finland (1/82) – the pay’s absurd, one’s own writing suffers from lack of time, it’s very hard to please people. And public demand for translation from minor languages into English was almost non-existent.

But he also admitted that translating is generally a pleasurable experience: ‘You have the pleasure of writing without the agony of primary invention. It’s like reading, only more so. It’s like writing, only less so.’ More…

Make or break?

17 November 2011 | This 'n' that

Two tax collectors: anonymous painter, after Marinus van Reymerswaele (ca. 1575–1600). Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy. Wikimedia

In Finland, tax returns are public information. So, every November the media publish lists of the top earners in Finland, dividing them into the categories of earned and investment income. Every November it is revealed who are millionaires and who are just plain rich.

The Taloussanomat (‘The economic news’) newspaper offers a list (Finnish only) of the 5,000 people who earned most last year (in terms of both earned and investment income, together with the proportion of income they have paid in tax). You can also search lists of various status and professions: rock/pop stars, media, sports, MPs, celebrities, politicians of various political parties…

So let’s take a look at Taloussanomat’s selected list of authors: number one is the celebrity author Jari Tervo (309,971 euros, tax percentage 45); number two, the internationally famous Sofi Oksanen (302,634 euros, 46 per cent); the next two are Sinikka Nopola, writer of children’s books, (264,000) and Arto Paasilinna (262,300; now after an illness, retired as a writer), translated into more than 30 languages since the 1970s. (The film critic and author Peter von Bagh made almost 900,000 euros – not by writing books, but by selling his share of a music company to an international enterprise.)

As tax data are public in Finland, there’s vigorous and decidedly informed public debate on how much money, for example, directors of public pension institutions and government offices or ministers and other top politicians are paid, and how much they should be paid: what is equitable, what is reasonable? A million dollar question indeed…

Among the European Union countries, it is only in Finland, Sweden and Denmark that there is no universal minimum wage. Here, wages are determined in trade wage negotiations. The average monthly salary in the private sector in 2010 was approximately 3,200 euros. In contrast to that, Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, the Nokia CEO and President, who tops the 2010 tax list, earned a salary of 8 million last year, because – and precisely because – he was sacked (and replaced by the Irishman Steven Elop).

The CIA’s Gini index measures the degree of inequality in the distribution of family income in a country. The more unequal a country’s income distribution, the higher is its Gini index. The country with the highest number is Sweden, 23; the lowest, South Africa, 65 (data from both, 2005). Finland’s figure is 26.8 (2008), Germany 27 (2006), the European Union’s 34. The United Kingdom stands at 34 (2005), and the USA at 45 (2007). The figure in Finland seems to be on the rise though, as the figure back in 1991 was 25.6.

There’s been plenty of research and debate on economic inequality and the ways it harms societies. This link takes you to a fascinating video lecture (July 2011 – now seen by almost half a million people) by Richard Wilkinson, British author, Profefssor Emeritus of social epidemiology.

Autumn’s child

17 November 2011 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Bo Carpelan’s novel Blad ur höstens arkiv. Tomas Skarfelts anteckningar (‘Leaves from autumn’s archive. The notes of Tomas Skarfelt’). Introduction by Clas Zilliacus

When I took my first walk here in Udda, along the road down to the end of the bay, my legs wanted to go left up to the forest, while I strove to walk straight ahead. It was an unsteadiness reminiscent of being slightly drunk. A slight vertigo I have already noticed before. Trees soughed through me and the water of the bay tasted almost like salt on my lips. All sorts of things try to pass straight through me nowadays. I am becoming a general store. The few people I know go there and choose, and I try to sell. Most of it is old memories with attendant dust. They are in no chronological order at all, and make involuntary, rapid leaps, like kangaroos. Even when I went to school they hopped around. They forced me to learn my lessons by heart. They continued to skip over me at university and added an extra complexity to my studies in general history: concentrate of reign lengths.

And if I followed my legs and gave not a damn about my dead straight road? Digressions from what was planned provided me later on with my best experiences, and coincidences were grains of gold. Improvisations were lucky throws, or disasters. Afterwards came the restrictions, the constructions, the architecture. Now only that squared-paper notebook remains with its pitfalls. The uncertainty is sometimes imperceptible, but is there: Am I not superfluous? Are not my legs somewhat irrational? More…

Finlandia Prize candidates 2011

17 November 2011 | In the news

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011 are Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Kristina Carlson, Laura Gustafsson, Laila Hirvisaari, Rosa Liksom and Jenni Linturi.

Their novels, respectively, are Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos), William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava), Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into), Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava), Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY) and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, Teos).

Kallorumpu takes place in 1935 in Marshal Mannerheim’s house in Helsinki and in the present time. Laila Hirvisaari is a popular writer of mostly historical fiction: Minä, Katariina, a portrait of Russia’s Catherine the Great, is her 39th novel. Gustafsson’s and Linturi’s novels are first works; the former is a bold farce based on women’s mythology, the latter is about guilt born of the Second World War.

The jury – journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman – made their choice out of 130 novels. The winner, chosen by the theatre manager of the KOM Theatre Pekka Milonoff, will be announced on the first of December. The prize is worth 30,000 euros. It has been awarded since 1984, to novels only from 1993.

The fact that this time all the candidates are women has naturally been the object of criticism: why are the popular male writers’ books of 2011 missing from the list?

Another thing that these novels share is history: five of them are totally or partially set in the past – Finland in 1935, Paris in the 1890s, Russia/Soviet Union in the 18th century and in the 1980s, and 1940s Finland during the Second World War. Even the sixth, Huorasatu, bases its depiction of the present day in women’s prehistory, patriarchy and the ancient myths.

The jury’s chair, Hannu Marttila, commented: ‘This book year is sure to be remembered for a generational and gender change among those who write literature about the Second World War in Finland. Young woman writers describe the war with probably greater diversity than before. From the non-fiction writing of recent years it is clear that the struggles and difficulties of the home front are increasingly being recognised as part of the general struggle for survival, and on the other hand the less heroic aspects of war, the shameful and criminal elements, have also become acceptable as objects of study.’

Marttila concluded his speech: ‘When picking mushrooms in the forest, I have learned that it is often worth humbly peeking under the grass, and that the most glaring cap is not necessarily the best…. Perhaps it is time to forget the old saying that there is literature, and then there is women’s literature.’

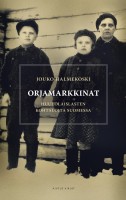

Jouko Halmekoski: Orjamarkkinat. Huutolaislasten kohtaloita Suomessa [The slave market. The fate of auctioned pauper children in Finland]

17 November 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Orjamarkkinat. Huutolaislasten kohtaloita Suomessa

Orjamarkkinat. Huutolaislasten kohtaloita Suomessa

[The slave market. The fate of auctioned pauper children in Finland]

Helsinki: Ajatus Kirjat, Helsinki, 2011. 225 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-20-8391-6

€ 26, hardback

Auctions of people were at their most widespread in Finland in the 1870s and 1880s; ‘auctioned paupers’ were entrusted for a year at a time to the one who put in the lowest bid for the pauper’s upkeep, then recompensed by the local authority. The people who were auctioned off included children, the elderly, disabled and mentally ill people. These auctions were banned in 1923, but they continued for some time thereafter. Although the practice was widely known about, the paupers’ shame prevented much discussion of the subject. Those who wished to provide help to people in need were probably greatly outnumbered by those who sought to benefit from their plight. In most cases, orphaned children ended up being auctioned off. Children born out of wedlock were another significant group. Jouko Halmekoski advertised in the newspapers in order to trace the lives and descendants of those who were auctioned off. Not all the auctioned paupers’ histories are tales of horror: this book, consisting of 25 of them, also includes stories of children who were treated well.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

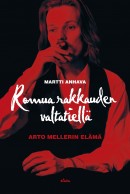

Martti Anhava: Romua rakkauden valtatiellä. Arto Mellerin elämä [Garbage on the highway of love. The life of Arto Melleri]

10 November 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Romua rakkauden valtatiellä. Arto Mellerin elämä

Romua rakkauden valtatiellä. Arto Mellerin elämä

[Garbage on the highway of love. The life of Arto Melleri]

Helsinki: Otava, 2011. 687 p., ill.

ISBN 976-951-1-23700-6

€ 36, hardback

Arto Melleri (1956–2005) has been called the last Finnish bohemian poet. At the age of 35, he received the Finlandia Prize for a collection of poetry entitled Elävien kirjoissa (‘In the books of the living’) as well as an invitation to the Independence Day celebrations at the Presidential Palace, from which he was thrown out. The literary editor Martti Anhava traces his friend’s life from his schooldays in Ostrobothnia to his turbulent life in Helsinki. There are interviews with family members, friends, writers, musicians, theatre-makers; Melleri wound up studying dramaturgy at the Theatre Academy. The year 1978 saw the presentation of Melleri, Jukka Asikainen and Heikki Vuento’s play Nuorallatanssijan kuolema eli kuinka Pete Q sai siivet (‘The death of a tightrope walker or how Pete Q got wings’). Breaking completely with the mainstream political theatre of the 1970s, it became a cult show. The last volume by this poet of bold, often cruelly romantic visions was Arpinen rakkauden soturi (‘The scarred soldier of love’, 2004).

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Warmer climes

10 November 2011 | This 'n' that

Up and away: Jukka is about to leave for the south. Photo: Hannu Vainiopekka /Finnish Museum of Natural History

Jukka spent the night of 9 October by the river Sana in Bosnia-Herzegovina. He then crossed the Croatian border, at times reaching a speed of 96 kilometres per hour.

By 15 October Jukka had crossed the border between Libya and Niger; 350 kilometres later he settled in the desert for the night. After entering Cameroon on the 21st, Jukka completed his journey of 34 days and 6,600 kilometres by landing on the bank of River Benoue and taking a well-earned break. In March it will be time to head homewards again, to Lake Pälkäne in Finland.

Jukka is a Finnish osprey.

Earlier, another osprey, Lasse, surprised the zoologists by spending his winter in Israel, instead of Africa. But Harri decided to wing his way as far as to South Africa, almost 12,000 kilometres from home, a distance he covered in some 57 days!

The Finnish Museum of Natural History / University of Helsinki and the Finnish Osprey Foundation track ospreys with the help of satellite tracking.

Long-distance travelling is dangerous, though: Eikka perished on his way to the south in Ukraine this autumn, and in 2008 Pete was probably eaten by a local eagle in Morocco: some of his feathers, as well as the transmitter were found beside a river by two officials of the Emirates Center for Wildlife Propagation, Eric Le Nuz and Rachid Khain.

Gone fishing: Jukka the satellite osprey having lunch. Photo: Hannu Vainiopekka/Finnish Museum of Natural History

And why this interest in wildlife, you might wonder? Oh, as we sit here and edit Books from Finland in the semi-darkness of a November afternoon, creatures that migrate just seem to come to mind. Not to mention hibernation, but that’s another matter….

Out of my hands

10 November 2011 | Articles, Non-fiction

Who's been eating my porridge? From ‘English Fairy Tales’ by Flora Annie Steel (1918), illustrated by Arthur Rackham. The Project Gutenberg e-Book

In the classic fairy-tale, on finding their belongings were not as they had left them, the three bears exclaimed: ‘Who’s been eating my porridge?’ When our technology correspondent Teemu Manninen found someone else’s underlinings in the electronic text he was reading, he wondered: ‘Who’s been tampering with my ebook?’ Which led him to ponder how similar books and their virtual counterparts really are – and could his ebook really be called ‘his’?

A few months ago I was reading an ebook on my iPad when I came across an underlined passage. For a moment I felt strangely disturbed. My initial thought was that I had not made the underlining, and therefore this had to be a glitch, an error in the computer program that was the book, which meant that there was something wrong with my book. What made this thought disturbing was the realisation that the kinds of harm that can befall digital books – and the measures that one can take to prevent them – are no longer ‘in my hands’: that the book is no longer physical, but virtual. More…

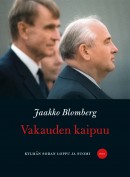

Jaakko Blomberg: Vakauden kaipuu. Kylmän sodan loppu ja Suomi [Longing for stability. Finland and the end of the Cold War]

2 November 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Vakauden kaipuu. Kylmän sodan loppu ja Suomi

Vakauden kaipuu. Kylmän sodan loppu ja Suomi

[Longing for stability. Finland and the end of the Cold War]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2011. 696 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-37808-3

€ 37, hardback

From Finland’s perspective, the termination of the Cold War era encompassed three significant processes: the Soviet Union’s policy of perestroika, or reform, and the disintegration of its empire; the end of the international arms race and the rise of joint security as a policy aim of the superpowers; and increasing European integration. This book devotes individual chapters to two phases of Finnish foreign policy – interpretation of the Paris Peace Treaty and Finland’s withdrawal from the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, which it had signed with the Soviet Union in 1948. The second part of the book focuses on the years 1992–94, when Finland applied to become a member of the European Union and forged relations with the new Russia. Finland’s position in those years was defined by Mauno Koivisto, a cautious president, whose memoirs have served as a key source of material for Blomberg. The negotiations surrounding the region of Karelia, which was ceded to the Soviet Union after the war, are illuminated further here. As a Finnish ambassador, Blomberg served in key roles within the Ministry for Foreign Affairs from the late 1980s to the early 21st century.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Helsinki Book Fair 2011

2 November 2011 | In the news

President Toomas Hendrik Ilves at the Book Fair: Viro is Estonia in Finnish. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation

The Helsinki Book Fair, held from 27 to 30 October, attracted more visitors than ever before: 81,000 people came to browse and buy books at the stands of nearly 300 exhibitors and to meet more than a thousand writers and performers at almost 700 events.

The Music Fair, the Wine, Food and Good Living event and the sales exhibition of contemporary art, ArtForum, held at the same time at Helsinki’s Exhibition and Convention Centre, expanded the selection of events and – a significant synergetic advantage, of course – shopping facilities. Twenty-eight per cent of the visitors thought this Book Fair was better than the previous one held in 2010.

According to a poll conducted among three hundred visitors, 21 per cent had read an electronic book while only 6 per cent had an e-book reader of their own. Twenty-five per cent did not believe that e-books will exceed the popularity of printed books, and only three per cent believed that e-books would win the competition.

Estonia was the theme country this time. President Toomas Hendrik Ilves of the Republic of Estonia noted in his speech at the opening ceremony: ‘As we know well from the fate of many of our kindred Finno-Ugric languages, not writing could truly mean a slow national demise. So publish or perish has special meaning here. Without a literary culture, we would simply not exist and we have known this for many generations, since the Finnish and Estonian national epics Kalevala and Kalevipoeg. – During the last decade, more original literature and translations have been published in Estonia than ever before. And we need only access the Internet to glimpse the volume of text that is not printed – it is even larger than the printed corpus. We live in an era of flood, not drought, and thus it is no wonder that as a discerning people, we do not want to keep our ideas and wisdom to ourselves but try to share and distribute them more widely. The idea is not to try to conquer the world but simply, with our own words, to be a full participant in global literary culture, and in the intellectual history and future of humankind.’

Finland meets Estonia: authors Sofi Oksanen and Viivi Luik in discussion. Photo: Kimmo Brandt/The Finnish Fair Corporation