Rooms with views

21 August 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Most of us live in box-shaped houses; the long-prevailing laws of modernist architecture relate to cubes, geometry and masses. Together with an architect, artist Jan-Erik Andersson designed a leaf-shaped house for himself. Could it be both art and architecture? In his new book he takes a look at non-cubical buildings in Finland and beyond, attempting to define what makes ‘wow factor architecture’: good architecture requires freedom from strict aesthetic rules.

Extracts from the chapter entitled ‘Det inre rummet’ (‘The inner room’) in Wow. Åsikter om finländsk arkitektur (‘Wow. Thoughts on Finnish architecture’, Schildts & Söderströms, 2014)

I remember from my childhood in the 1960s how my brother and I each lay in our beds in a little room late in the evening and stared up at the ceiling, onto which the lights from cars outside cast patterns. The patterns were constantly changing, they were like the doors of imagination onto eternity. Along with the hum of the engines they lulled me into a kind of half-stupor.

During the days the floor of the room grew to a town as we threw ourselves into a world of adventures and sped around with Formula 1 cars. Or the waste-paper bin was squeezed into a corner between the bookshelf and the wall, and the room took on the dimensions of a basketball court.

When defining a room it is difficult to distinguish between the outer, physical room, and the inner room formed by your consciousness.

Outwardly it looks simple. Stone, wood, concrete, clay, steel and glass are used to create a house (or a hut) as a shield against nature. We can knock on the wall outside and it’s like any big physical object. But when we step (or creep) inside, and perhaps light a fire to warm ourselves and make ourselves feel safe, a change takes place. The shield can be as small and fragile as a cardboard shack, yet it gives us the intimate room experience that allows us to imagine.

In La poétique de l’espace (The Poetics of Space) the philosopher Gaston Bachelard regards the house as one of the strongest driving forces for people’s thoughts, memories and dreams. The binding principle for this is daydreams.

As adults we must make sure not to let go of the ability to imagine. A window in even the smallest abode can open up the experience of the room to the whole world. I tend to lie down on the beautiful sofa by the window and let my gaze follow the clouds as they float away. Soon I’m sitting on an airplane, and after a while in a rocket leaving the Earth to disappear into the ice-cold meteor shower.

More and more gaps are appearing in the physical walls. The Internet is the latest means of enlarging the mental room. Digital means of communication and preserving images will broaden our concept of the room both backwards and forwards in time, and change our relationship with the surrounding world on many levels.

In this respect I am not thinking about the widening of the mental sphere which video and audio chat entail, and nor am I thinking about the significance of computer programmes in creating architecture with organic forms. I believe that the virtual frees us from the line of thinking that architecture moves forward in a linear fashion, and that a new style must express the zeitgeist. Of course it is no hindrance that new materials are being invented all the time, increasing the possibilities available within the field of architecture.

In the virtual – and visual – world we live in in the early 2000s it is, however, easy to forget that perhaps the most effective tool when it comes to imagination is still the written word – on paper or on a tablet. In a good bed, in an intimate room, late at night when the world around has grown quiet, by reading you can freely allow fictive worlds to shape your mental room.

As a child my mental environment was heavily shaped by the stories that were read to me or that I later read myself. I feel that stories have the ability to create a mental room in your consciousness, one which you can return to later in life when seeking shelter and security.

In my experience these virtual rooms, or atmospheres, created by imagination along with fragments of memories and the stories of fairytales, are important for our mental health. My thesis and starting point is that these mental rooms should have a reflective surface to be activated and reproduced in the environment in which we live and operate. For this to happen it is important that the architecture we live in is stimulating in its shape, its ornamentation, and spatial structure. Unfortunately only a very small amount of the architecture created today works in this way. To be able to tangibly research this I decided to build my own house, Life on a Leaf in collaboration with the architect Erkki Pitkäranta. The house also constitutes the production element of my doctoral thesis at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki.

It doesn’t have anything to do with nostalgia and a yearning to return to my childhood – I am very happy to have escaped from it – instead, it has to do with the fact I truly believe that the atmosphere that characterises fantastical stories is universal. It should be seen as an important ingredient when we shape our ‘adult’ world too.

Why is there such a sharp contrast between the child and adult worlds? Why is it seen as childish to live in a house that is individual, represents something, and is bursting with colour? Why don’t we see, between the millions of box-shaped houses, one sole one shaped like a hat, a flower or a shoe? Why is minimalism such a strong force within today’s architecture in Finland? Isn’t it the decorative, descriptive and caring energies which let us create an environment we enjoy being in – an environment which at the same time is more ecological because of the desire to seek out experiences in other cultures is decreasing?

What role does visual art play in relation to architecture? Would it be possible to picture a symbiosis where architecture and visual art are integrated, and figurative ornamentation, sound art, and an ecologically sustainable construction concept combine to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, a comprehensive artwork.

Art & architecture: Handelhögskolan (Hanken School of Economics) in Helsinki, 1950. Architects: Hugo Harmia & Woldemar Baekman, ceramic ornaments: Michael Schilkin. Photo: Jan-Erik Andersson

Most often we refer to economic factors as justification for architecture being ‘serious’ and minimalist. But I want to claim that just as often, aesthetic choices are what guide architecture in a direction in which vivid ornamentation is replaced with ‘tastefully’ integrated abstract details and surface structures that have no reference to anything apart from themselves and technology. Even though development is gaining a freer outlook when it comes to construction, there are still only few architects who dare to create architecture based on dreams, nature, stories, playfulness, colour and ornamentation. Here I’m referring primarily to the situation in Finland, as our cultural surroundings are what I know best.

The negative reactions of many Finnish professional architects to the Life on a Leaf house show how deadlocked the situation is, and for me it has exposed the vague philosophical basis on which many architects’ houses stand. Professor emeritus Kaj Nyman wrote a letter in which he warned me against building it, because there was absolutely no way we would enjoy living in the house! The internationally renowned Finnish architecture philosopher and architect Juhani Pallasmaa refuses to see our house as architecture.

I have been fortunate enough to have also received a large number of positive responses, above all from those who have visited the house. But also from elsewhere. The RIBA award winning English architect Will Alsop sent an email containing the comment: ‘I love it!’ Professor Georg H. Marcus’s bookTotal Design: Architecture and Interiors of Iconic Modern Houses [to be published in October 2014] presents complete works of art from the last hundred years. Two houses from Finland are included: Gesellius, Lindgren & Saarinen’s Hvitträsk and our Life on a Leaf house on the island of Hirvensalo in Turku.

But what matters most is the fact that my minimalism-favouring partner and I enjoy our house greatly!

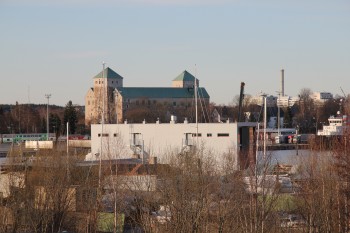

A view from the Leaf House: between it and Turku Castle, from ca. 1280, the new addition of modernist architecture, an office building (CC-M Arkkitehdit, Caterina Casagrande-Mäkelä, 2011). Photo: Jan-Erik Andersson

I have become more and more convinced that something has gone seriously awry in Finnish architectural training today. The fact things look so sad and lifeless in our build environment is often blamed – from an architectural perspective – on engineers and developers having taken over control.

I would like to point out that it is the minimalist-modernist aesthetic ideal of the leading architects that has made this development possible. If the bare cube in different versions of white-grey-black represents the ideal, then the cubes can just as well be drawn by engineers. Architecture should really be focused on something completely different.

As soon as possible we should phase out the current strict architecture ideal and create greater freedom. Unfortunately the heightened framework and new regulations have meant that architecture competitions nowadays even require detailed heating, plumbing and ventilation plans. This, along with the expensive 3D renderings required to create an attractive entry, mean that small architectural firms quite simply can’t afford to take part in competitions. Furthermore, when the competition jury more often than not features the same people that maintain the current system, it is very difficult to bring about any change to the current state of affairs.

If we can’t influence the big architectural and engineering firms that take charge of the important projects as well as of mass architecture, one possible strategy is to retreat, to criticise and write. It is not surprising that no architecture criticism exists in Finland today – the big firms hardly want to see any.

If the big players can’t be influenced, we can create alternatives and more freedom for home builders. We should, for example, support those who want to change their lifestyle and plan houses with self-sufficient systems.

What is good architecture, then? Many draw a distinction between building and architecture. To get a building to stand upright and hold water are matters for engineers. Architects aren’t needed for that. Architects should work with the psychology of the dwelling and the visual effect the building has on its surroundings. Here we should broaden all the learnt values which so often now lead to meaningless houses with boring façades – and which are often also badly built. We should teach architects and engineers to draw houses that would draw a WOW! even from uninitiated viewers. Fantastic buildings don’t need to be more expensive. It is not my mission to encourage everyone to build leaf-shaped houses, instead it is more a matter of widening the concept of architecture, which has taken on far too abstract and fixed a meaning.

The title of this book comes from the concept used to describe expressive architecture from recent decades, with Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao being one famous example. Abroad, the term ‘Iconic Building’ is often used when describing wow-architecture, with ‘Iconic Building’ being a wider term for design language associated with phenomena outside architecture. For example, Gehry’s museum can be described as a shoal of fish. The title of the book of course also refers to the fact there have always been buildings – and hopefully always will be – buildings that fascinate people.

Good architecture can indeed look like anything today. It can be a white box, it can look like a frog or a leaf, there are no rules here. Architecture as an aesthetic system is dead! Long live architecture!

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Jan-Erik Andersson’s Elämää lehdellä (‘Life on a leaf’, Maahenki, 2012) will be published in English shortly by AraMER (ISBN 978-94-9177-553-6. Contact: info@merpaperkunsthalle.org)

Tags: architecture, art, design

No comments for this entry yet