Extending the Bounds of Reality

Issue 1/1976 | Archives online, Authors

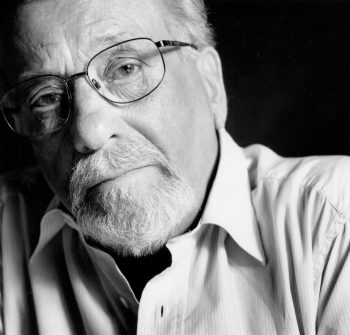

Christer Kihlman. Photo: Magnus Weckström

In any account of Finnish literature written in Swedish during the 60s, the name of Christer Kihlman stands out clearly. For long influential in his native Finland, it is only more recently that he has become well known in Sweden.

Apart from his verse, all his works have been translated into Finnish and several of his novels have also appeared in other Scandinavian languages. Of late he has been writing for the theatre. Christer Kihlman has received important Finnish and Swedish literary prizes and in 1975 was appointed a professor of the arts. Kihlman was born in 1930.

Christer Kihlman’s writing bears many traces of the left-wing radicalism that has characterized much of the literature of the 60s and 70s. He has contributed actively to the discussion of cultural and political issues, both in his novels and in the articles he has written on a wide variety of problems. He has endeavoured to eliminate the conflict that normally arises between an author’s political activity and his creative work, though this has been by no means a painless process. “Our field of activity is society as a whole. The written word, our principal tool, gives us only a limited opportunity to leave a tangible mark on social development, but we should not allow this to deter us from trying: the results of our efforts, after all, can never be determined in advance. Our aim is, and should be, the same as everyone else’s should be: an ever-broadening, everdeveloping democracy. To be an author is, as I experience it, to live one’s life as a social being in a social context, in the full consciousness of what this social context implies and what it demands in terms of intellectual awareness and moral preparedness.”

Between Generations

Early in the ’50s Kihlman published two collections of poems which echoed the modernistic style that had been adopted by Finland-Swedish poets in the ’20s. Then began a long and arduous period of preparation for the novels, during which he worked mainly as a literary critic. The novel Se upp Salige (‘Look up blessed ones’, 1960), brought his name to the notice of a wider public. The setting of the novel is a small town in a Swedish-speaking area of Finland. With a few deft surgical strokes Kihlman lances the festering abscess that lurks behind the respectable facade of small-town society, mercilessly exposing the falsity of bourgeois attitudes to morality and property. The book provoked sharp reactions from people who thought, rightly or wrongly, that they were being attacked or slandered. Today we can see that it was concerned with wider issues than the activities of any particular people in any particular place. The self-absorption and stuffiness of small-town life is a world wide phenomenon. In his perceptive moral analyses, his exploration of the depths of human destructiveness and degradation, Kihlman is sometimes reminiscent of Faulkner, one of his favourite authors. Ignoring all the flashbacks and shifts of level that occur in the novel, the plot can be summarized very briefly: the middle aged editor of a bourgeois newspaper, Karl Henrik Randgren, comes to terms with himself and his past, and with his bourgeois environment.

A recurring theme in Kihlman’s novels is the ‘generation gap’. In Se upp Salige Randgren is shown in relation to two members of the younger generation: his 16-year-old son, offspring of a shattered marriage, and the 14-year-old Lolita-figure Annika, who is the daughter of one of his radical friends. Preoccupied with his own personal troubles, he is too busy seducing Annika to pay proper attention to his son. (In his editorial capacity he would of course maintain that when a young person goes off the rails, it is the parents who are to blame.) The end is catastrophic: the son commits suicide, while the father’s own attempt at rebellion, being based merely on emotion, crumbles away to nothing.

Kihlman seems to be saying that revolt of some kind is always necessary. The son must rebel against the father, while the father must realize – as Randgren fails to do – that the phase of revolt is a positive stage in a young man’s development. For the adult, too, revolt is important: in his case a constant revolt against stagnation of spirit and inelasticity of thought. In Kihlman’s novels, revolt is always presented in a favourable light, even when the revolt is unsuccessful or takes a highly destructive form.

Den blå modern (‘The blue mother’, 1963) is an even more broadly conceived novel about conflict in family relationships and between the generations. Two brothers, Raf and Benno, hold the centre of the stage. The former is a writer and a socialist, who suffers from violent inner conflicts and has a leaning towards self-destruction. His brother Benno represents the forbidden, shadowy sides of life. Via homosexuality and mental illness he comes to experience a religious conversion – the only salvation from the disrupting forces of existence. Den blå modern is a family chronicle in the modern style, making use of such devices as monologues, dream sequences and allegorical tales. The novel owes some of its inspiration to William Styron’s Set This House on Fire – certain features of its structure are borrowed from Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield.

The action swings between Rome and a small town in Finland. The author’s skill is apparent in the way he can switch without awkwardness from the horrors of a Nazi concentration camp to the domestic dissensions of an ordinary family. Raf seeks to achieve a kind of worldly humanism which will not altogether exclude the unknowable or the inexplicable from the concept of humanity. The message of the novel is that the manifold variety of life must be accepted, even when acceptance hurts. The final section, ‘Sun over Ausschwitz’, contains some of the most brilliant pages written in Swedish during the 60s.

Se upp Salige and Den blå modern can also be seen as political novels. Both are concerned with a necessary and painful revolt against the life-denying moral attitudes of a stagnating bourgeois society. In these books Socialism defines a moral as well as a political stance. Kihlman’s central characters look upon Socialism not as a ready-made system of dogma but as something living and changing: a method of approach, which must be constantly revised as changes occur in the world itself. This implies, too, that the result achieved by an act of revolt is itself impermanent. The mind must remain open, the revolt – against fossilization, against lovelessness, against political conservatism – must be constantly renewed.

Repeatedly Kihlman attempts a formulation of his vision of existence as a totality: “Underlying every occurrence there is a pattern, a uniting and unifying factor which does not arise directly out of the occurrence, but which gives it significance; just as the roots of trees bind together the soil we cultivate in a mysterious fine-grained symmetry, and the crop does not depend directly on these roots – indeed we remove them so as to obtain a better harvest – and yet, where there have been no roots to bind the soil together, the land is a desert and cannot be cultivated.”

All the characters in Kihlman’s novels are reaching out towards this vision of totality, of wholeness. Their difficulties and inner struggles are often due to their inability to find a connection between the self and the outer world. This connection has to be constantly re-established. To write is to seek, says Kihlman through the mouth of Raf in Den blå modern: “I must look right into the pictures, leaf them over, look long and carefully, and yet I know nothing, nothing at all. It is an art. To search blindly, like a mole, for the incomprehensible – our world and our life.”

Self-examination

The contrast between the self and the external world recurs in the third novel, Madeleine (1965), a work conceived on a smaller scale than its predecessors, and executed with great delicacy of style. If his earlier novels represent (to use a metaphor of his own) “a hewn-out block of reality”, Madeleine is a glittering sliver chipped from the surface of the selfsame rock. Outwardly the setting is idyllic: a family spending a long hot summer in a remote place by the sea. Contact with the outside world is confined to Raf’s brief trips to the capital and the occasional visits of Fred, a close family friend, who has a cottage in the neighbourhood. The central figure is Raf, who is a left-wing intellectual, a writer, and an alcoholic. Events and experiences are described as they present themselves to his fuddled brain. Written in the form of diary entries, the novel takes the reader through Raf’s obsessive soliloquies and wide-ranging stream of consciousness, which does not flinch from the regressive symptoms to which he is subject at regular intervals. Raf forces himself ever further into the depths of human degradation; his alcoholism becomes a kind of pact with death (compare Malcom Lowry’s novel Under the Volcano).

At the centre of Raf’s inner world stands his wife Madeleine. Her name becomes a potent incantation, which he repeats over and over again in his despair. She is the mother-figure, the symbol of security to which he clings. She, for her part, regards her husband’s drinking as a form of unfaithfulness, and embarks upon an affair with Fred, the family friend, as a last desperate attempt to escape from the hell of her marriage. Raf holds himself aloof from his wife and children, and becomes more and more dependent on the bottle and the world of fantasy. Meanwhile, through the newspaper headlines, he is fully conscious of the march of political events. His crisis takes the form of a refusal to retain any contact with the world around him. He sinks into a deep nostalgia for the lost garden of childhood. The novel begins and ends on the November evening when the news of President Kennedy’s assassination broke upon the world.

In Madeleine the author sets out, by exploring the deepest abysses of degradation and self-abasement, to affirm a belief in the necessity to accept life in its totality. He is attempting to extend the bounds of reality into the realm of the ugly; “for it is the ugly, not the beautiful, that demands acceptance if death is to be overcome”. Raf realizes that death’s promise of peace, sleep and reconciliation is a lure that must be withstood. In the end he comes to understand how fragile are the foundations upon which human love and fellowship, if they are to exist at all, must rest. Madeleine is written in a lyrical prose that reminds us that the author began his career as a poet.

Self-revelation

In Människan som skalv (‘The Man who lost his grip’, 1971) he lays aside the mask of the novelist and appears in his own character. This work is something between a novel and a book of confessions; the author himself calls it “a book about inessentials”. Without any fictional disguise, he describes his own experiences under three heads: as a homosexual (or rather bisexual), as an alcoholic, and as a partner in a disastrous marriage. His purpose in revealing so much of the inner self is to reduce, in some measure, the needless and irrational dread by which so many people are oppressed. This ‘essay-novel’ is one of the most ruthlessly self-revealing books that have appeared in Finland, and has, perhaps for that very reason, been the object of widespread discussion and controversy.

In Dyre Prins (‘Sweet Prince’, 1975) Kihlman, reverting to the novel-form, shows us a middle-aged, self-made businessman looking back over what he has made of his life so far, and giving us, in the process, a panoramic view of the social history of Finland from the time of the war right down to the 70s. At the same time the central character is ruthlessly stripped of his mask and his ‘successful’ life exposed for what it has been, a tissue of deception, cynicism, brutality and compromise. The novel deals with three important but difficult relationships in which he has been involved: with his relatives, with his wives, and with his children. Part of the action takes place in London.

Like many of the younger Finnish prosewriters of today, Kihlman is concerned with the unavoidable problem of the conditions of our very existence. The individual is a participator in a historical event, which to him appears chaotic and meaningless. It is through a consciousness of the community of mankind, and solidarity with it, that we can reach beyond the frontiers of despair. It is this painful knowledge of the necessity for endurance, this compelling need to extend the bounds of reality, that gives Kihlman’s work its weight and stature.

Translated by David Barrett

Tags: classics, Finland-Swedish

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

-

About the writer

Ingmar Svedberg (1944-2015) was a Swedish-speaking Finnish author, journalist and literary critic who often worked with the Finnish Broadcasting Company (YLE) and Hufvudstadsbladet daily newspaper. He also taught literature at the University of Helsinki and the Theatre Academy Helsinki in addition to being the chairman of the Society of Swedish Authors in Finland.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.