On Pentti Saarikoski

Issue 4/1977 | Archives online, Authors

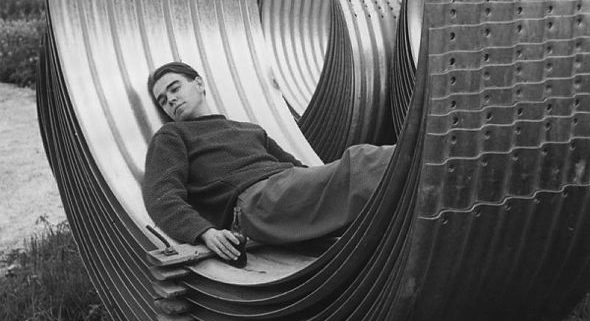

Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). Photo: Markku Rautonen / Otava

Born in 1937, Pentti Saarikoski was one of the many Finnish children who were evacuated to safety in Sweden during the Second World War. For almost twenty years – 1958–1975 – he had a sensational career as the enfant terrible of the new wave of post-war Finnish verse and as a translator of classical Greek poetry. Now Saarikoski is once more in Sweden, where he lives in a kind of spiritual and intellectual exile. The vast scope of Saarikoski’s work as a translator reveals the breadth of his interests and poetic skill. Among his translations into Finnish are works by Aristotle, Euripides, Sappho, Theophrastus, Xenophon and Homer’s Odyssey (a free verse translation that has been particularly praised for the freshness it brings to the work). Saarikoski’s translations of J. D. Salinger and Henry Miller have introduced modern urban slang into Finnish literature, and together with his brilliant translation of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1964) epitomise the catholicity of his interests. Saarikoski’s first poems were written in the spirit of ‘Finnish Modernism’: short poems, pleasing in their treatment of language, subtly erotic and ironic, drawing their strength from a fleeting image, metaphor or momentary fancy. Early in the 1960s, Saarikoski emerged from his scholarly retreat. He became a favourite of the yellow press and of television, he was held in the awe normally reserved in other parts of the world for royalty and pop stars. He loved this publicity and the scandal he deliberately created: he saw his function as to provoke the youth of the day to reject established ideas of authority and morality. He further outraged the middle classes (into which he himself was born) by joining the Communist Party.

It was during this period that Saarikoski published two major works of poetry. Mitä tapahtuu todella? (‘What really happens?’, Otava, 1962) is a mischievous carousel of language which combines the trivial and the lofty in total confusion, the broad social point of view that Saarikoski expounds in the collection owes its origin to a curious juxtaposition of Karl Marx and Ezra Pound. The second of these two works, Kuljen missä kuljen (‘I go where I go’, Otava, 1965) is characterized by a sense of resignation and struggle against despair. His theme is entropy; Saarikoski cannot fight the laws of nature – he feels himself growing tired, like physical systems that are running out of energy, ceasing to function. In the late 1960s, Saarikoski drifted into a life of bohemian alcoholism. His Kirje vaimolleni (‘Letter to my wife’, Otava, 1968) is a confession cast in the form of a novel, describing how the poet lives a life of total abandonment while in Dublin. His approach to this is a kind of mental behaviourism, recording with naive honesty the most infantile mental processes of a drunkard.

At a national level Saarikoski identified himself most closely with Eino Leino (1878–1926), the great Finnish poet who worked in many fields: translating, journalism, occasionally plunging fiercely into politics. An outcome of Saarikoski’s preoccupation with his spiritual predecessor was the long poem Eino Leino. This work, part narrative, part biography, often collage-like in form, appeared in 1974.

During its liberal period in the 1960s the Finnish Communist Party employed Saarikoski as a contributor to its publications and as an editor; he even stood as a Communist candidate for Parliament. But towards the end of the decade, however, the influence of the Stalinist wing of the party grew, and radicals like Saarikoski ceased to be any further use. Katselen Stalinin pään yli ulos (‘I look out over Stalin’s head’, Otava, 1969) is a long poem about that period. Saarikoski describes socialism as ‘a different kind of longing from my own longing.’

Several short collections of tightly constructed, pithy poems about the process of love and nature followed this work. Saarikoski’s political frustration was one of the reasons for his voluntary exile: since 1975 he has been living in a small house in the country near Gothenburg. There he continues to translate classical authors into Finnish – he is currently working on the Iliad. From time to time the poet lets the world know what he is thinking and working on, as in his latest collection Tanssilattia vuorella (The dancing-floor on the mountain’), published simultaneously in autumn 1977 in Finnish (Otava, Helsinki) and Swedish (Dansgolvet på berget, Bonnier, Stockholm).

The main theme of Tanssilattia vuorella is woven around the myth of the Minotaur. The world today is seen as a fossilized labyrinth, at the centre of which lurks a man-eating monster. But no Theseus comes forth: only time and erosion can help mankind escape its tragic bondage. On the few occasions when the poet does refer to present-day events, it is in oracular terms. Saarikoski, the classicist, aims at a reality that is not bound to history, he seeks to extract from transitory and insignificant occurrences those qualities whose significance transcends the measured passing of time. Tanssilattia vuorella is one of Finland’s two entries for the 1978 Nordic Council Literature Prize.

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Pekka Tarkka

Tellervo Krogerus: Sanottu. Tehty. Matti Kuusen elämä 1914–1998. [Said. Done. The life of Matti Kuusi, 1914–1998] - 22 May 2014

In good company - 18 October 2013

Nationalism in war and peace - 3 May 2012

In memoriam Bo Carpelan 1926–2011 - 24 February 2011

Arne Nevanlinna: Hjalmar - 5 November 2010

-

About the writer

Pekka Tarkka (born 1934) is an author and literary critic. Among his works are an extensive biography of the poet and writer Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) and of the author Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934; first volume, 2009; the second volume, 2012).

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.