A modern mystery play

Issue 4/1983 | Archives online, Authors

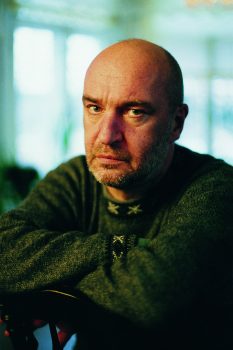

Jussi Kylätasku. Photo: Pertti Nisonen.

Jussi Kylätasku (born 1943) is a prolific writer of poetry, plays – stage and radio – film scripts and novels. Iconoclastically he casts aside the realism that is so characteristic of Finnish drama and so beloved by Finns; but at the same time Kylätasku is very Finnish: paradox is, indeed, characteristic of this infuriating writer, who has delighted critics and public alike. Perhaps the best-known of his plays is Runar ja Kyllikki (‘Runar and Kyllikki’), which was first performed in 1974; his newest work is a novel, published in November by Werner Söderström. One of his most revolutionary plays, however, is Maaria Blomma (‘Mary Bloom’), which might be called an extraordinary modern version of a mediaeval mystery play. What follows is a personal view of the director of the first performance of the play, in 1980, Väinö Vainio.

There are drama scripts, technically assured texts addressing themselves to the burning issues of the day, that inspire one at first reading to predict fruitful interpretations and lasting recognition. Unfortunately, in the Finnish theatre world such forecasts seldom come true. Almost without exception, even those plays whose first performances are successful fall into the jaws of Moloch and rapidly pass into obscurity on dim and dusty archive shelves.

From time to time, on the other hand, a maverick piece comes into one’s hands, a script in which everything seems somehow out of place – the subject, the style, the dramatic technique. One can’t imagine why it was written or how it could possibly be staged. But in reading it one feels one’s face growing hot with excitement; the chaotic collisions of style make one restless; one throws the manuscript aside in disgust, only to take it up again next day. Jussi Kylätasku’s Mary Bloom is such a play.

Set in a threadbare circus tent, the play is a story of belief and doubt, of a girl who ‘sought, found, took and used the power to work miracles’. Mary’s manager, the ex-priest Otto, announces that the audience will see – ‘before your very eyes’ – Mary Bloom performing the greatest miracle since the birth of Christ’: Otto’s wife Serenity, ‘an innocent virgin’, will be ‘delivered of a child who will be the saviour of the world’. Otto promises that the sick, who are crowded in the front rows, will be healed, the blind will see, the ears of the deaf will be opened, the lame will walk and the alcoholic will be cured of their addiction.

Although the play may seem to be more than a grotesque parody of a revivalist Christian meeting where miracles border on charlatanry, its true concern is something completely different. Throughout Mary Bloom’s incredible career, she steadfastly denies that her power is of God; it resides instead, she insists, within herself. And furthermore, she says, the same power is to be found in everyone, if only it can be recognized. ‘Can the saving Power save a world that is poised on the brink of doom, can mankind perform the miracle upon itself?’ asks Mary Bloom in one of her central monologues.

Mary Bloom, a play about the hope and despair of the individual in the worldwide concourse of mankind, overflows with paradoxes. Not the smallest of the problems is a technical one: how to record a radio play whose success depends upon the presence of an audience that reacts spontaneously. The congregation at the revivalist meeting is built into the script in such a way that the play cannot succeed without a live audience.

In the first performance of Mary Bloom, this was indeed how we proceeded. The script was rehearsed, and in part recorded, in studios in Tampere and was broadcast through loudspeakers in the Pyynikki Sports Hall, where it was billed as a form of public entertainment of an unusual kind. The performance, which was recorded and subsequently broadcast as a radio play, received the 1981 Prize for Theatre Happenings. Mary Bloom was soon taken up with enthusiasm for performance by both professional and amateur theatre groups.

Like most dramatists, Jussi Kylätasku does not readily make public comment on the success of his plays or on their meaning. In connection with the first performance of Mary Bloom, however, he described the seven-year gestation of the play as follows:

‘Fear of death in the individual has brought into existence tempestuous and long-lasting religions. Now it seems that this has been replaced by fear of our extinction as a species. If this should bring out in us a sense of responsibility and an understanding of the relationship of our lives as human beings to the world as a whole, if we could find a way to reach ourselves and each other, then there would be almost nothing that we could not achieve. Logic demands that we build our Utopia quickly. Once the catastrophe has happened even a miracle will be too late.’

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: drama

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

-

About the writer

Väinö Vainio (1942–2016) was a director and dramaturge, originally from Tampere, who worked on radio plays at YLE Radio for many years. He worked with a great many prominent writers of his era.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.