In a class of one’s own

18 December 2009 | Reviews

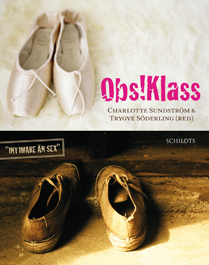

Obs! Klass

Obs! Klass

Red. [Ed. by] Charlotte Sundström & Trygve Söderling

Helsingfors: Schildts, 2009. 288 p.

ISBN 978-951-50-1891-5

€27, paperback

De andra. En bok om klass

Red. [Ed. by] Silja Hiidenheimo, Fredrik Lång, Tapani Ritamäki, Anna Rotkirch

Helsingfors: Söderströms, 2009. 288 p.

ISBN 978-951-522-665-5

€26.90, paperback

Me muut. Kirjoituksia yhteiskuntaluokista

Helsinki: Teos, 2009. 267 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-259-5

€27.90, paperback

At some time in their lives, all members of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland have been confronted with the phrase ‘Swedish-speaking better people’ [Svenska talande bättre folk], uttered in tones of contempt. Encouraged by news and entertainment media with little regard for the consequences, Finland’s Finnish-speaking majority is hopelessly fascinated by the image of us Finland-Swedes as a uniform and monolithic haute bourgeoisie that resides in the coveted Helsinki neighbourhoods of Eira and Brunnsparken.

To someone like myself who grew up with Swedish as the language that was spoken both at home and at the school I attended in the not very fashionable 1960s Helsinki suburb of Gårdsbacka [Kontula] (known during my youth as a ‘problem district’, or slum), with no links either to the Finland-Swedish cultural bourgeoisie or to the nation’s capital city nearby, this is both sad and offensive. And it’s a predicament I share with many Finland-Swedes – we don’t recognise ourselves in that hostile cliché, but whatever we say about ourselves falls on deaf ears.

At least now we have two really good books we can quote from when we try to present our arguments. By happy chance, two anthologies about class in Finland have appeared from the two leading Finland-Swedish publishing houses at the same time. The first, with the title Obs! Klass (‘NB! Class’), proclaims on its cover that class is ‘more intimate than sex!’. Which may be true in Finland, where the upper class is a social stratum so thin that it is barely noticeable in the city and even less so in the countryside – unlike Sweden, the nearest Nordic democracy, which has an aristocracy with its own peculiar anthropological features and a number of castles and country estates that shape the rural landscape. In Finland, for better or worse, major joint projects like nation building, war and the rapid urbanisation of a population of smallholders have overshadowed many of the special interests connected with class.

Although this has not prevented the segregation of rich and poor, it has been harder to describe in conventional terms of class. For this reason, a de facto Finland-Swedish mixed-class minority (small farmers, fishermen, workers, officials, impoverished academics and a few well-off individuals) has become the country’s only visible target for class hatred, long after most of the wealth and prosperity drained away into other channels, even from the tiny handful of representatives of the Finland-Swedish upper class that once existed.

Söderling’s and Sundström’s editorial choice of contributors to Obs! Klass is expressly designed to render visible the Finland-Swedes who were hitherto unseen – the ones who never owned a fortune, or who lost it long ago. In this they brilliantly succeed.

The other anthology, De andra (‘The others’, Me muut), was published in Swedish and Finnish editions at the same time, with contributors from both language groups. It makes a good companion to Obs! Klass, expanding and filling it out in a useful way. The book tends to concentrate on the distinctions that create the sense of familiar and other that we all live with in our everyday lives. This is all extremely interesting, but I am not sure that it is really about class.

The most insightful contributions in both books are those that concern education. In Obs! Klass Robert Åsbacka (born 1961) analyses his education all the way from childhood in a conscientious working-class environment to the status of published author and Ph.D. student in literary studies, including how long it took him to turn his ‘history’ into ‘capital’, i.e. convert his educational career through manual labour into cultural capital and a decent livelihood. All without a financial safety net, or role models at home.

Charlotte Sundström (born 1973, in the same book) describes her class journey from fisherman’s daughter in the small Ostrobothnian village of Öja to cultural journalist in Helsinki, calling it – correctly enough – an ‘educational’ one. In the 1980s, Finland still had an educational system that was based on a sincere desire to iron out class differences and give everyone an equally good start in life by means of good primary education, regardless of their background at home. The economic recession of the 1990s marked the beginning of the dissolution of that ambition, and the results have made themselves felt –we live in a society where some schools are ‘problem schools’ and others flourish, society cannot fix the problems with special initiatives and well-off parents are increasingly able to choose between different alternatives. Among today’s thirty-something academics Sundström’s story is not unusual – the hardworking girl who becomes part of a meritocratic system and is able to put her talent to use – but there is a danger that the country may become a new, harsher, socially segregated Finland.

Malin Slotte’s moving essay (she was born in 1973 in the same part of Ostrobothnia as Sundström, and is also a cultural editor) concerns a similar journey, but with a focus on the experience of alienation and uncertainty among those who enter the domains of middle-class education with no prior knowledge of cultural codes and who only have their reading skills to help them. Maria Antas (born 1965) is another example of someone who received a healthy, meritocratic education which none the less left behind a certain degree of mistrust and an awareness of differences that lie below the surface.

In De andra there is an essay that forms a sister text to the accounts of these talented women. But it also contains a complication they lack or (Slotte, Antas) only hint at: what does it mean to leave one’s parents behind, to become quite different from them and feel relieved about doing so?

Merja Virolainen (born 1962) pays tribute to the Finnish comprehensive school that freed her from a life of intellectual narrowness and uncouth manners – a school that offered her knowledge, aesthetic experiences, broader horizons. And not only to the school: ‘I view my class background and development from four perspectives: education, health, occupation and income. Our education system, public libraries and national health service have been crucial to my development in terms of class. I dare say that I have them to thank for most things in my life. ‘

Although I suspect that Virolainen’s home background was a lot more spartan than mine, I (born 1958) second her vote of thanks with all my heart. I have also chosen to highlight precisely these texts because they concern something precious that risks being lost – the Nordic welfare model, a state that wants its citizens to prosper.

![]()

In addition to the examples I have mentioned, if one reads these two anthologies together one can find countless interesting pieces of information about Finnish society as well as opinions on them. One can learn what it’s like to make the journey from middle-class daughter to suburban single parent in Helsinki’s lower middle-class slums, to teach at an élite high school while having obligations to one’s family in Ghana, what it’s like for a fox farmer to go bankrupt and how pängar (the Åland pronunciation of the Swedish word for money) talks on the Åland Islands [which lie between Finland and Sweden, and have Swedish as the dominant language] just as it does in the global economy.

Alas, what we discover least about is what it’s like to live without financial worries. The wealthy contributors (Maria Björnberg-Enckell, Niklas Herlin and Sophia Ehrnrooth, heirs of successful industrial families) have many interesting things to relate about class, culture, society and wartime experiences cutting across social barriers and having different effects. But even after this worthwhile read, most of us can still only fantasise about what it must be like to have money.

Perhaps having plenty of money just feels natural – ‘nothing to write home about’ – to those who have it? In her role of local politician and debater Maria Björnberg-Enckell has established a reputation for being able to provoke people. Many readers will also probably be made extremely angry by her partly clueless but also wise and thought-provoking contribution to De andra. It, too, is the story of a hardworking woman, but one who grows up to be an active woman with truly inspiring ideas about good upbringing, who believes that noblesse oblige, and whose family history is codified in real estate (the stately home, the summer retreats).

‘The attention, the demands and the respect I got from home have given me faith that my actions have meaning and that I myself have chosen them. For me as a parent, upbringing – both unconscious and self-taught – meant making demands on my children and giving them attention (…) Anyone can raise their children to be people who do well. Worldliness and a secure position in society do not come into being in secret rooms, but probably in homes where they are seen to be important. It’s the challenge that is the motivating factor,’ she writes. Perhaps for those of us who wonder ‘what it’s like to have money’, the key is hidden in those words. Björnberg-Enckell was able to choose to be hardworking. Some of us have no option. And motivation only works up to a certain point – the point where one’s money and strength run out. Perhaps being rich is simply never having been in that situation.

* In modern Finland the Swedish-speaking minority, known as Finland-Swedes, constitute about six per cent of the population. Finland is officially a bilingual country. Swedish was the language of the Finnish bourgeoisie and the intelligentsia throughout the 19th century, long after Finland was annexed to Russia in 1809 following centuries of Swedish rule. Finnish slowly gained status as the language of public education as the struggle for independence became stronger in the early 20th century.

Translated by David McDuff

Tags: Finnish society, identity

No comments for this entry yet