A day in the life of a bookseller

12 August 2010 | Reviews

The bookseller Aapeli [Abel] Muttinen, a central figure in Joel Lehtonen’s ‘Putkinotko’ books, is one of those fictional characters for whom Finnish readers have cherished a particular affection, not least because of his keen enjoyment of the pleasures they themselves so regularly share when they escape to their lakeside cottages for the summer.

But although Aapeli Muttinen is Finnish through and through, he is not without counterparts in the literature of other nations. One of his close relatives is the laziest man in all literature, Goncharov’s Oblomov; others, perhaps more surprisingly, can be found in the works of Anatole France – booksellers like Blaizot and Paillot, both gentle dilettanti with a streak of individualism and a penchant for good living. Like them, Muttinen is tolerably well-read: at the beginning of the short story ‘A happy day’ we find him musing about Horace, and at least one of Horace’s odes must have appealed to him strongly: ‘Happiest is he who, like his sires of old, / Tills his own ground, and lives his life in peace, / Far from the tumult of the noisy world.’

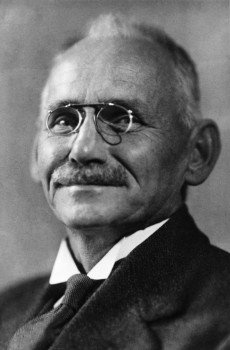

Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934) had a stormy and eventful life and travelled in many parts of the world. His most important literary achievement was the series of four books, published between 1917 and 1923, now known collectively as the ‘Putkinotko’ (an onomatopoetic, invented place name, it could be translated as Hogweed Hollow) books: two novels, Putkinotko, Kerran kesällä (‘Once in summer’) and two books of stories, Kuolleet omenapuut (‘The dead apple trees’ from which ‘A happy day’ is taken), and Korpi ja puutarha (‘The wild wood and the garden’).

In these works Muttinen is sometimes the central character, sometimes a figure in the background, revealing, as the books proceed, an intriguingly complex and contradictory personality with elements not only of the comic, as seen in his exaggerated hedonism, but also of the grotesque and even of the tragic.

We meet him first in Kerran kesällä: born in squalid poverty, a man of energy and resource who makes his own way in the world, ending up as a quite prosperous bookseller, a kind of local Maecenas with his own devoted circle of budding poets, some mediocre, some hardly even that.

Muttinen is an elitist: conspicuous on his shelves are the works of Homer, Cervantes, Rabelais, Swift, Voltaire and Aleksis Kivi (Lehtonen’s own favourites). Undoubtedly he has good taste, but this makes it even more difficult for him to swallow the bitter truth that he has achieved his wealth and elegant life-style by the sale of ‘50-penny dreadfuls’ – trashy adventure novels and love stories – to the small-town bourgeoisie.

Another sizeable slice of his profits has come from the sale of religious and devotional works, and this too goes against the grain; Muttinen disapproves of the Church and the clergy and he is an enemy of conventional morality. ‘Why,’ he splutters indignantly, ‘why should the Church bind two people to each other for life? Married people can hardly ever get along together. Why can’t they be free, like the birds and the foxes and the field mice? How beautiful it would be, to go forth and people the earth – so long as they could part when they wanted to!’ This doctrine Muttinen puts into practice by living openly with his mistress Lygia. There has been an earlier marriage, to a certain Fanni, but even before leaving the altar steps he says to her ‘We’ll separate at once if ever you want to go. ‘ The marriage does not last long, thanks partly to Fanni’s habit, when annoyed, of emptying a jug of soured milk over Muttinen’s lecherous head.

Muttinen’s ideals, as far as private life is concerned, are happiness, freedom and security. Politically he is a pinkish Liberal. Sometimes he quotes barbed epigrams from Bernard Shaw: over his bed hangs a portrait of Tolstoy, from whom he has adopted the maxim that no man must live by the toil of others and no man must practise violence. He is opposed to chauvinism and militarism, and maintains that the barriers between rich and poor must be broken down.

There is a marked contrast between these doctrines of Muttinen’s and his actual way of life. ‘A person needs money in order to bea person,’ he says. He is rich and he owns land, but he does not ‘till his own ground’, as Horace puts it: the work on his summer estate is done by a crofter. Juutas Käkriäinen and his large family live in dire poverty: he pays rent for the privilege of tilling Muttinen’s fields. The novel Putkinotko describes the relations between the educated landowner and his humble tenant. Muttinen plays the enlightened despot, the humanitarian, full of benevolent charity towards these ‘children of nature’.

But his strategy fails, for Käkriäinen rises in revolt. In Kuolleet omenapuut we read how the civil war of 1918 breaks out, partly as a result of just such grievances over the system of land ownership. Aapeli is sent (more than half against his will, for he is a coward as well as a pacifist) to fight in the front line on the side of the Whites. In a fit of rage he shoots a Red prisoner, ‘a brother human being’. Abel has become Cain, the pacifist has become a killer. For him it is total shipwreck.

![]()

‘A happy day’ depicts Muttinen’s life at Putkinotko in the days when his green paradise is still inviolate, untrampled by the cruel march of history. There he relaxes in the lap of Nature, free of thoughts and free of memories. However, the contrast between the bookseller’s altruistic principles and his natural egotism shows itself yet again, this time in the context of an intimate relationship.

For one entire day the landscape ‘loses its true dimensions’ under ‘the boundless blue of the kindly sky’. But there are also intimations of a darker side to the picture: the churchyard, the eerie sadness of the cowbells, the blackness of the water beneath the lovers’ boot.

Translated by David Barrett (1914–1998). This article and the translation of the short story ’A happy day’ were first published in Books from Finland 4/1981

Tags: classics

No comments for this entry yet