Paris match

30 June 2011 | Articles, Non-fiction

In 1889 the author and journalist Juhani Aho (1861–1921) went to Paris on a Finnish government writing bursary. In the cafés and in his apartment near Montmartre he began a novella, Yksin (‘Alone’), the showpiece for his study year. Jyrki Nummi introduces this classic text and takes a look at the international career of a writer from the far north

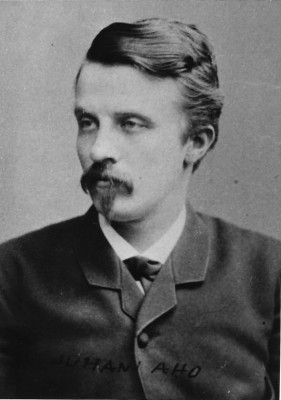

Juhani Aho. Photo: SKS/Literary archives

Yksin is the tale of a fashionable, no-longer-young ‘decadent’, alienated from his bourgeois circle, and with his aesthetic stances and social duties in crisis. He flees from his disappointments and heartbreaks to Paris, the foremost metropolis at the end of the 19th century, where solitude could be experienced in the modern manner – among crowds of people. Yksin is the first portrayal of modern city life in the newly emerging Finnish prose, unique in its time.

Aho’s story has parallels in the contemporary European literature: Karl-Joris Huysmans’s A Rebours (1884), Knut Hamsun’s Hunger (1890) and Oscar Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1890).

The novella reflects the innovatory trends of the period. At the end of the 19th century the new prose was no longer interested in a story line that traced an individual’s course of life. The story was chopped, spatially and temporally, into sequences, which didn’t produce a connected narrative or create a well-constructed plot but sought recurrent situations, motifs, images and symbols, patterns and rhythm. Aho’s classic novel of 1884, Rautatie (‘Railway’) is still a product of realism; but the lyrical prose in Yksin is closer to the art of poetry than rapportage. This kind of artistry – which Aho himself discussed in the 1880s in his newspaper articles on Finnish prose – is connected to the pictorial art of the period. The facial profile of the adored Anna, who has rejected the narrator, is a recurrent, lyrical leitmotif.

Aho was personally but unrequitedly enamoured of the young upper-class beauty Aino Järnefelt. When her future husband, the composer Jean Sibelius, read Yksin in Vienna in 1890, he was so enraged he swore to write a letter challenging Aho to a duel. The letter was never posted.

The critics of the day were mostly confounded by the novella’s structural and stylistic innovation. Particularly indigestible was the climax, where the narrator spends Christmas Eve at Le Moulin Rouge in the company of a prostitute.

Aho’s bold Parisian sojourner stirred up public contention, precisely as the writer had hoped. In 1891, discussing literary prizes, the Finnish parliament had a vigorous debate on whether government bursaries were at all necessary. Yksin was soon published in Swedish as well. Observing the furore from Sweden, the Aftonbladet newspaper critic commented aptly: ‘It was a description of the kind of goings-on qui se font, mais qui ne se disent point (‘things that do happen but are not spoken about’).’

Aho also recognised the importance, from the beginning, of the translation of his works, which demonstrates his clear understanding of literature as a market-area that transcended national boundaries. Leafing through Juhani Ahon kirjallinen tuotanto (‘Juhani Aho’s literary oeuvre’, edited by N.P. Virtanen, 1961), one is amazed how much, and into how many languages, Aho has been translated.

There is, of course, a wide range in the languages in which Aho’s work has appeared. As generators of cultural production, Paris and London decided literary standards. Access to the markets of the metropolises meant not only the opportunity to reach the broad Anglo- and Francophone readerships, but was also a trump card that had its uses on the home market. The centres of the time remained cool toward Aho: he has been translated only a little into English and French. The German literary world, on the other hand, embraced Aho warmly. Many translations were published, representing the best of the writer’s work.

His most important market, however, was Sweden, where translations of Aho’s work were issued immediately, right up to his last book, Muistatko –? (‘Do you remember – ?’,1921). Aho’s reputation in Sweden became considerable as early as the 1880s and 1890s. It is difficult to say whether his fame rested only on its literary merits, or on the sympathy toward Finnish literature that Swedes felt toward little Finland during a period of intense Russification in the Grand Duchy. This big-brother attitude may well explain Aho’s later succes in Stockholm, when the Swedish Academy began, at the beginning of the new century, to give the Nobel Prize for Literature, which has become the world’s premier literary award.

The status of the prize is uncontested today, and there is perhaps no greater proof of the international convergence of literary standards than the global attention the prize receives every year. The prize is awarded on the basis of a long-term study of the writer’s work and literary statements from independent experts.

Aho had been a candidate for the Nobel Prize for the first time as early as 1902. From 1910, he was suggested regularly right up to 1921. Aho’s candidacy was at first marked by a benevolently positive attitude, which was felt, in particular, toward the aspects of his work which were felt to be idealistic.

In 1913 the history professor Harald Hjärne was appointed chairman of the award committee. Hjärne had a particular view of Finland’s cultural position, and in his literary summaries he repeatedly quashed the idea of awarding Aho the prize on the grounds that Finnish-language literature could not be thus recognised without simultaneously giving an award to Finland’s Swedish-language literature. When no individual named writers were proposed, the chairman himself suggested the Finland-Swedish poet Bertel Gripenberg. Since, on the other hand, no independent expert had suggested Gripenberg, it was logical, in terms of this masterly piece of prestidigitation, that the prize could not be awarded to Aho either.

Hjärne had no knowledge of the development of Finnish society; neither did he understand the increasing linguistic overlap that was developing in Finland despite the minor skirmishes of day-to-day politics. The Swedish-language writers Runeberg and Topelius had become part of Finnish-language literature, just as the Kalevala had become part of Swedish-language literature. Juhani Aho’s generation had also started a development in which Finnish- and Swedish-language literature were increasingly regarded as Finnish literature that was written in two languages.

The Aho internationalisation project demonstrates the strength of the period’s centre-periphery links as well as the inequality that was hidden in these structures. In order to achieve international fame outside the centres, it was necessary to seek the approval of markets in Paris and London. With any luck, the next stop was Stockholm. Successful tours were made later by many writers, such as the American William Faulkner, the Colombian Gabriel García Márquez, and the Chinese Qao Xinjian.

Juhani Aho stepped forward from a very young literary tradition. He achieved critical success in his local environment, but never really made an international breakthrough. This is visible in the international canons of the period. They include, incontrovertibly, Ibsen (from Norway) and Strindberg (from Sweden), but not a single Finnish writer.

Aho’s internationalisation project, however, was the starting shot for a lengthy development after which now, a hundred years later, looks as if Finnish-language literature has attained international significance which is not limited to sales figures and film deals, important as they are.

Last year the young writer Sofi Oksanen received, in Paris, recognition that no other Finnish writer had earlier achieved. Having first garnered every possible Finnish literary award, then the Nordic Literature Prize, her third novel, Puhdistus (Purge, 2008) won, in the autumn of 2011, the important French literary award, the Prix Femina.

Puhdistus achieved the most important prize of all: it became accepted, recognised and admired by the Parisian literary establishment – like Aki Kaurismäki in film and Kaija Saariaho in music. The years to come will show whether Oksanen’s unprecedented success will be crowned by the hundred-year project begun by Juhani Aho and his generation, whose aim was to place Finnish literature and culture in the European time zone.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: classics, literary history, novel, translation

No comments for this entry yet