Madness and method

10 May 2012 | Authors, Reviews

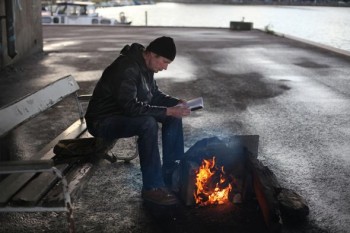

Juha Hurme. Photo: Stefan Bremer

One day during Advent in Helsinki the narrator in the novel Hullu (‘The lunatic’, Teos, 2012), a middle-aged man, goes mad.

Complete confusion fills his mind. He thinks he must be dead, but nevertheless manages to knock on the door of the mental hospital. To his amazement, he is admitted to the yellow building.

Because the boundaries between reality and self are, for him, completely blurred, he believes that the people in the hospital know absolutely everything about his unsuccessful life, and that he must expect humiliations and punishments. The people in white coats are aliens, or perhaps holograms.

In one of the rooms of the next venue, the white building, he sees his mother as she was 30 years ago. His room-mate is some kind of observer, the toilet door is a gateway to oblivion, the Gateway of Final Departure.

Our man tries to find consolation and sense in reading and in his books. But how a poem by Bertolt Brecht describes, in exact detail, his life-story! The pain of knowing! The paralysis of fear! ‘It was one hundred per cent pure, genuine terror – odourless, colourless and tasteless, free of causes and consequences.’

Time works very strangely, but a slow return to a shared reality begins. A notice board gives details of how life in the third, grey building works. Breakfast: 8.00. Lunch: 11.45. That is understandable, but what does this mean: ‘Clothing care individual’?

Becoming acquainted with other patients gradually brings social turning points. In the mornings, the sounds of the building have a soothing effect: ‘It was new that I began to perceive that there were other people pottering about, with their sorrows, their joys, their loves and their confusions’. ‘… I was once more a part of life, although I had only a very small stake in it. You can feel and communicate by listening, too, even if nothing more were ever to happen.’ Terror subsides.

‘I am but mad north-north-west; when the wind is southerly I know a hawk from a handsaw,’ said Hamlet: the return of a thespian begins gradually. He recognises the difference between illusion and delusion.

Around New Year the patients act, as a read-through, a play written and directed by the narrator. It tells the story of Josef Julius Wecksell, a Finnish poet who wrote verse and plays in Turku in mid-19th century until he went mad and spent 42 years in the silence of a mental hospital. The play, however, moves freely between the late16th century and the year 2015.

‘Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.’ The entire script of the play is included in the novel: its 65 pages include comments by both the director and the actors as well as events external to the drama. The performance ends with one of the patients playing air guitar. ‘We drank our evening tea. Mikko [a nurse] stayed on to supervise and we other actors swallowed our medicines and passed out into our beds. The rockets exploded and the year changed, I presume, but of that we no longer knew anything.’

‘What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty!’ The narrator gradually picks up the pieces, rediscovering his reason, his nearest and dearest and his place in the world.

In this, his third novel, the theatre director and dramatist Juha Hurme (born 1959) describes a psychosis and recovery from it. In his story, he weaves a complete play text together with the stories of his main character and his fellow patients; a vivid imagination may play its part in the descent into madness, but it can also play a strong part in surviving it.

The reader of Hullu empathises with the patients, whom Hurme describes with artless but profound humour and deep sympathy: both human tragedy and comedy live behind the closed doors of the mental hospital.

Hurme’s main character takes up the role of a dramaturge in the closed community, simultaneously rebuilding his own self-understanding. ‘All relations in the world are interactive relations.’

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: novel

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Soila Lehtonen

Colour me beautiful? - 29 June 2015

Leena Krohn: Erehdys ['The mistake'] - 8 June 2015

Minna Lindgren: Ehtoolehdon tuho [The downfall of Twilight Grove] - 1 June 2015

Pekka Lassila: Maininki [Surge] - 5 May 2015

-

About the writer

Soila Lehtonen is a journalist and theatre critic and the Editor-in-Chief of Books from Finland from 2007 to 2015. She edited a collection of writings about the city of Helsinki together with Hildi Hawkins, Helsinki: a literary companion (The Finnish Literature Society, 2000).

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.