Do you speak my language?

23 August 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

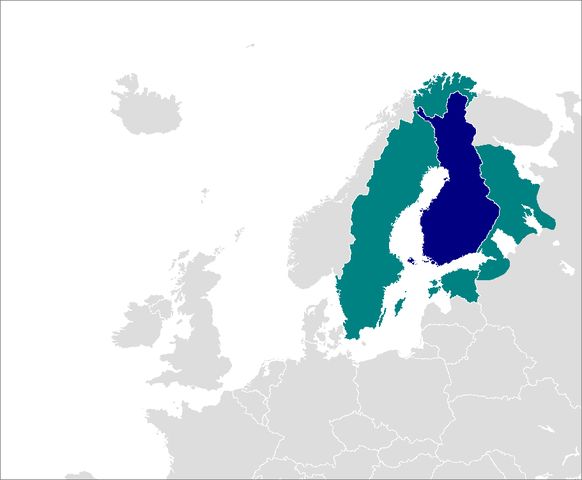

Finnish spoken outside Finland: Sweden (west), Estonia (south), Karelia/Russia (east), Norway (north). Illustration: Zakuragi/Wikipedia

Finland has two official languages, Finnish and Swedish. Approximately five per cent of the population (290,000 Finns) speak Swedish as their native language. All Finns learn both languages at school, and students in higher education must prove they have an adequate knowledge of the other mother tongue. But how do native speakers of Finnish cope with what is, for many of them, a minority language that they will never need or even wish to use? We take a look at bilingual issues – and a new book devoted to them

‘In many parts of the world, language can be a fiery and divisive issue, one that pits the powerless against the powerful, the small against the big. The Basques battle the Spanish. The Flemish tussle with the Walloons. The Québécois scuffle with the rest of Canada.’

That is how Lizette Alvarez illustrated her theme in her article ‘Finland Makes Its Swedes Feel at Home’, published in the New York Times in 2005.

In Finland, language has been a fiery issue at times, though things have cooled down a bit since the early 20th century. The use of Finnish as a written language dates back to the 16th century, but the territory of Finland was part of the Swedish Empire until 1809. Swedish was spoken by the nobility as well as most of the peasant class – the mechanism of the state did not serve Finnish-speaking peasants or other segments of the population in Finnish.

During Finland’s era as a grand duchy of Russia (1809–1917) Swedish was retained as an official language, but the status of Finnish improved. Finnish did not acquire official status alongside Swedish until 1919. Since 1992, the law has also guaranteed the Sámi people in Lapland the right to use their own language in official contexts.

Both national languages are taught in Finnish schools, and university students must prove that they possess adequate skills in whichever of the national languages is not their mother tongue. In recent years compulsory Swedish has engendered passionate opposition – the obligation to learn Swedish is regarded as a burden when Finns are supposed to learn two foreign languages (in line with a European Commission objective), and critics deem global languages to be a greater priority.

For example, a student of Finnish literature would need skills in the minority language in order to understand both Finnish history and contemporary culture, but a future car mechanic living in eastern Finland more often than not finds school Swedish lessons a waste of time.

The old popular conception of Finland-Swedes as ‘posh’ people (the former aristocracy) and representatives of the better-off classes still lives on in the minds of Finland’s linguistic majority – although the fact is that statistically speaking, the most typically Finland-Swedish occupation nowadays is that of a fisherman who lives on the west coast.

As a result of historical and natural factors, the linguistic landscape in Finland is complex and unique. One thing that is clear, however, is that the identities of the Finnish- and Finland-Swedish-speaking populations are both basically Finnish: in Finland, people ‘think Finnish’ in two languages.

A new book, published in both Finnish and Swedish, presents a variety of views on bilingualism. The authors of Rakas Hurri! 15 näkökulmaa kaksikielisyyteen / Kära Hurri! 15 synvinklar på tvåspråkighet i Finland (‘Dear Hurri![pejorative term for a Finland-Swede]: 15 views of bilingualism’, Schildts & Söderströms, 2012) each have a different official language as their mother tongue. Should everyone be able to speak two official languages – and how well?

‘In cultural-historical terms, Finland-Swedes are a relatively young and well-integrated language minority group engaged with the national population,’ says Riie Heikkilä, a social policy researcher.

‘Compared to other linguistic minorities, Finland-Swedes are a remarkably heterogeneous group. “Rural Finland-Swedes” and “cultural Finland-Swedes” continue to live separate lives: among the sources for my doctoral dissertation [2001] there is no evidence of a single shared discourse; relations between the provinces and Helsinki or between rich and poor are really quite strained. For example, a fisherman from the Ostrobothnian coast explained at length how he feels he has much more in common with the Finnish speakers who work alongside him than with someone living in Helsinki from a very different socio-economic class who just happens to speak the same language as he does.’

The populist claim that ‘Finns speak Finnish, which has always been spoken in Finland’ does not hold true – and it never has, as Juha Ruusuvuori, an author living in a Swedish-speaking area on the south coast of Finland, writes:

‘The first Dominican and Franciscan friars came to settle on the Finnish coast in the 13th century. They were monks from abroad: even Henrik, Finland’s first bishop, is believed to have come from England. As a result of Swedish influence, Finland came to be governed by the rule of law rather than a ‘punish first, ask questions later’ approach. Because our country became an important part of Sweden, we did not end up in serfdom, as happened in nearly every other European country – to say nothing of the situation in Russia. We were able to retain the same Swedish laws when Finland came under Russian control in 1809 [which lasted until the Independence, 1917].

‘Were we Finns monolingual? Hardly. There is no information on the languages spoken here before our own era. For over a thousand years, Swedish – perhaps along with Estonian – has been spoken along our coast. Sámi has been used in the forests, while Karelian and Russian have been spoken in the marketplaces of Karelia. Danish has been heard in Finland’s fortresses and German in its cities along with Finnish and Swedish. The educated classes even conversed among themselves in Latin.’

Neurologist and writer Markku T. Hyyppä defines bilingualism and Swedish-language nativeness in Finland:

‘I have spent half my life in a Finland-Swedish environment, the core of which is constituted by my own family. When it’s necessary – such as with my wife, friends and Swedish or bilingual speakers – I speak Swedish. Yet I am not bilingual; I am a person with one mother tongue who speaks a foreign language. Being able to understand and use a second or additional language as an adult does not make a native speaker of one language into a bilingual or multilingual individual. We need a definition of true, genuine bilingualism so as to avoid disastrous misunderstandings. True bilingualism means the ability, acquired in early childhood, to think and speak fluently in two languages (also known as ambilingualism).

‘The Finland-Swedes of Helsinki are bilingual, whereas those in Ostrobothnia in north-western Finland and the outlying areas in the south-west around Turku remain a monolingual Swedish-speaking population. Being bilingual broadens one’s perspectives and would help members of the minority to cope in mainstream society in Finland and elsewhere as well. For Finland-Swedes who are genuinely bilingual, even if they speak faultless Finnish, they may not be able to shake off the majority’s stereotype of them as posh people (bättre folk, “better people”, in Swedish). The Finnish-speaking majority are envious of Finland-Swedish culture, despite not having any in-depth knowledge of it. ’

Writer and critic Johanna Koljonen illustrates Swedes’ surprising lack of awareness of the situation of Finland-Swedes:

‘Living in Sweden, I’ve had to explain my Swedish-language yet thoroughly Finnish identity on many occasions. While St Lucia festivities, Midsummer poles and snaps drinking songs [folk traditions originating in Sweden] are part of my native Finland-Swedish culture, they do not indicate anything about a particular inborn Swedishness. Swedes aren’t German, even though they listen to schlager music, eat pumpernickel bread and drink glögg. As I often say: calling a Finland-Swede Swedish is just as silly as calling a Brazilian Portuguese.’

Journalist and lecturer Johanna Korhonen values the language she has had to learn – and would like to speak it more:

‘I really enjoy living in a bilingual Finland. The national languages I speak are Finnish and pidgin Swedish. I learned the latter at school in Oulu, the city where I was born, where I never met a single native Swedish speaker. My approach is to babble on in pidgin Swedish, with no hang-ups…. The Swedish language in Finland has been preserved through isolation. Swedish-language school and cultural institutions exist in a different world to Finnish-language ones. Finnish-speaking children are not admitted to local Swedish-language schools, because the schools fear that Finnish-speaking families keen on the Swedish language will hijack the school, kill off Swedish and cheer when mostly Finnish is spoken during breaktimes.

‘Easy-going, problem-free bilingualism requires a completely different sort of cultural strategy. It requires nurseries, schools and other educational institutions that enable continuous, regular encounters between Finland’s official languages. It requires jobs, organisations, clubs, gyms and choirs where people happily speak pidgin Swedish and broken Finnish. That’s where friendships and networks of acquaintances are created.’

The level of Swedish taught in schools or even required at university level is no guarantee that Finnish-speaking learners of Swedish will be able to use the language well, as Rosa Meriläinen, an author and MP (Green Party), writes:

‘I contend that the crunch point regarding the status of Swedish for us Finnish speakers concerns whether or not a person has learnt Swedish to an advanced level and whether they consider their language skills to benefit them in their own lives. Those who have not learnt or benefited are justified in asking: what is the purpose of all this trouble and continual humiliation and sense of inferiority caused by a language skills requirement which they see as excessive? In reality, poor Swedish – that is, school-level Swedish – is of no use at all.

‘I am incapable of speaking or reading Swedish. However, I have excellent school Swedish. I even received a distinction in school Swedish in my school-leaving exams. Unfortunately there is no place for school Swedish in the adult world, as you only see people who speak proper Finland-Swedish or Rikssvenska [the Swedish of Sweden] at conferences in the Nordic countries and in the Swedish-language media…. I myself received a piece of paper from my university which says I am competent to hold a public-sector post in two languages. In reality, I am unable even to write a job application in Swedish.

‘So if we want to guarantee a sufficient number of bilingual people for a bilingual nation, we need to direct our attention to the world of adults rather than children: how to get willing Finnish-speaking adults to cultivate their skills in Swedish.’

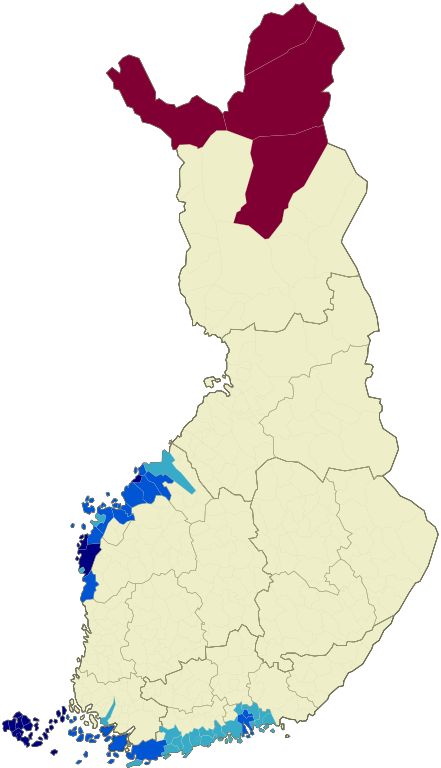

in 1910 11 per cent of the population spoke Swedish as their mother tongue, today the figure is around five per cent. At the moment there are 19 Swedish-speaking (dark blue) and 31 bilingual municipalities in Finland, with either Swedish or Finnish as majority language (blue and blue-green). In areas marked with red Sámi is a minority language. Illustration: Wikipedia

John Vikström, a bilingual emeritus archbishop, sets out one of the critical views that have been put forward in the debate around pakkoruotsi, ‘forced Swedish’, which is how Finnish-speaking Finns refer to the compulsory Swedish lessons in schools and universities:

‘As the prevailing view has it, children from eastern Finland end up having to learn Swedish so that Swedish speakers from southern and western Finland can access national and local services in their mother tongue.’

In Vikström’s view, though, Finland does have a need for a collective national cultural identity as well as a need to maintain Finns’ relations with Nordic cultural spheres, values and modalities, and widespread Swedish language skills are relevant to those needs.

However, to those who are opposed to Finnish speakers’ obligation to learn Swedish, an argument tied to such abstract matters is not necessarily all that persuasive. Finns have a very high language barrier to scale in every direction, so the opponents of Swedish prioritise global languages in foreign language teaching. Learning Swedish will not help a Finn get by in all of the ‘Nordic countries’ which are usually bundled together: Swedish is not spoken in Denmark, Norway or Iceland, even though their languages are Scandinavian. Those Finnish speakers who want to go into public-sector careers where Swedish is required can study it separately.

Päivi Storgård, a journalist and vice-chairperson of the Swedish People’s Party (Svenska folkpartiet i Finland), also raises some problems that the rise of stunningly narrow-minded populism in the 21st century has brought about:

‘I do not want anyone ever to be subjected to threats for defending their heritage, language or culture. Least of all my children, who are already restricted to speaking Swedish in the school building and with their friends and their relatives on their father’s side of the family. Last summer, a little girl ran over to her mother from where she had been queuing to buy an ice cream. Some old man had ordered the girl to speak Finnish, because she was in Finland. The child of a friend of mine came home from school, where he had heard a brand-new word. Some bigger boys had said that a bounty had been placed on Swedish speakers’ heads. Never in the world do I want to hear the question, “What does ‘bounty’ mean?” It’s time to put a stop to talk that infringes people’s human rights. Everyone has the right to their own heritage.’

Pia Ingström, a bilingual Finland-Swedish journalist, author and literary critic, had this to say about Finland-Swedes’ right to use their mother tongue in a bilingual country:

‘Within the space of a few years, the climate of public opinion has changed into one where grown men and women bully and shout at children for speaking Swedish on public transport. There is no way to safeguard bilingualism for yourself or others when the linguistic majority’s loathing for Finland-Swedes has been deliberately whipped up in a wave of political populism. If this means that I’m forced to choose which one I am – a loathesome “Swedo” or an acceptable Finnish speaker – well, then, I’m a Swedo, no doubt about it.

‘In the language environment – in Finland and Helsinki – I currently live in, Swedish is that part of my bilingual identity that requires special protection to prevent it fading into a language for use only at home. The Swedish language needs Swedish-language spaces.’

Translated by Ruth Urbom

More discussion, in English – some of it rather fiery – is found on these pages of the Ovi Magazine: I and II

Rakas Hurri! 15 näkökulmaa kaksikielisyyteen. Kära Hurri! 15 synvinklar på tvåspråkighet i Finland

Toim. [Edited by]: Myrika Ekbom, Mari Koli, Johanna Laitinen

Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 128+128p.

ISBN 978-951-52-2941-0

Tags: Finnish society, identity, language, politics

5 comments:

27 August 2012 on 5:21 pm

Dear Editors ,

Approximately , four per cent of the Finnish population speak Swedish as their native language . This very small percentage does not qualify the Swedish for being an official language with the Finnish in Finland .

There were abnormal circumstances during Finland’s era as a grand duchy of Russia made Swedish as an official language . This abnormal situation continued until now .

On one hand , ‘ Forced Swedish ‘ as an official language and the compulsory lessons in schools , and university Finnish-speaking students are obliged to prove that they possess adequate skills in Swedish , show how much the Finnish-speaking Finns are suffering , and how much time they waste to learn a local language ( Swedish ) which is of no use for them , whereas they are supposed to learn two foreign languages in accordance with the European Commission objective . On the other hand , adults , throughout the world , deem global languages to be a priority to seize good opportunities for getting jobs .

The time has come to make Finnish the sole official language , and to break the shackles by dropping Swedish from the university entrance exam , and to learn both languages , Finnish and Swedish , at school voluntarily , not compulsorily . Also , it is necessary to mix the Swedish-speaking Finns into the whole Finnish society through relationships by marriage between Finnish and Swedish speakers .

Finally , it is not correct to call the Swedish-speaking Finns as the Finland-Swedes , because they are Finns speaking Swedish .

Nihad A. Rasheed

Novelist , translator and free-lance journalist

6 September 2012 on 1:09 pm

Presently we have bigger problems in Europe than whether we should encourage Swedish speaking in Finland or not.

We encourage biodiversity, why not also cultural diversity. (Historically Swedish influence existed long time before Finland became part of imperial Russia in 1809).

Regarding marriage maybe we leave it to the young couples themselves to decide whom they will marry. Marriages are not arranged in Finland; that is not our custom.

So if and when only one language would be spoken, then what? Would we have less unemployemnet, domestic violence, shootings and child abuse? I am not convinced.

Proud to be a Swedish-speaking Finn I definately feel myself part of the whole Finnish society!

(I cannot contribute to semantics of English as English is my third language; started it in the 6th grade.)

7 September 2012 on 4:55 pm

Dear Mr Rasheed,

Thank you for your interesting comment.

We do not, however, agree that the time has come to make Finnish the ‘sole official language’; neither do we feel that it is appropriate to speak about ‘mixing the Swedish-Speaking Finns into the Finnish society by marriage’ – the populations are already thoroughly mixed; besides, as Gunilla Holmberg points out in her comment, marriages are not arranged in Finland.

Finland-Swedish is an adjective in general use to describe the mother tongue of Finns who speak Swedish. Its origin lies in the days when Finland formed part of the Swedish kingdom and the greater entity was known, in Finland at least, as Finland Sweden.

We also agree with Gunilla Holmberg: monolinguality by itself is no great shakes: diversity is always better, linguistically as well as otherwise, and even within a single country.

16 September 2012 on 7:40 am

My dear Soila Lehtonen ,

First of all I’m so sorry because I couldn’t reply previously , I was in a short visit to India .

I read with great interest your nice commentary . I agree with you entirely , you have no idea how much I appreciate your opinion .

Nihad A. Rasheed

16 September 2012 on 10:48 am

Dear Ms Gunilla Holmberg ,

I agree with you completely , the cultural diversity is very important . Finland , with Finnish and Swedish speaking Finns , is a cultural mosaic . But I didn’t call upon arranging marriage , because marriage is the social institution under which a man and woman establish their decision to live as husband and wife by legal commitments , etc. I meant that it is important to let both communities , the Swedish and Finnish Finns , live together , not separately , in order to create good chances for marriage .

I’m from Iraq , I visited Finland in 1970 , and read its history , which was filled with bravery and heroism . Finns engaged in wars in order to prove their Finnish identity . And I’m sure that all the Swedish – speaking Finns are proud of their country Finland like you .

On one hand , I have been publishing many short stories , poems , and articles about the Finnish short story , novel , poetry , and theatre , in the Arab world journals , since mid 1970s , and I played a big role to hold the Finnish – Iraqi cultural symposium in Iraq in 1979 , and I participated in a lecture about the new Finnish drama . On the other hand , I’m fond of the Swedish – Speaking writers , such as :

Johan Ludvig Runeberg , who is the national poet of Finland . He was the most famous Swedish –Speaking writer of the nineteenth century .

During the early 20th century , the Swedish – language modernism emerged in Finland as one of the most acclaimed literal movements in the history of the country . The best known representative of the movement was Edith Sodergran .

The most famous Swedish – language works from Finland are the moomin books by Tove Hansson , as well as : Bo Carpelan , famous poet , Jorn Donner , aurthor , Monika Fagerholm , novelist , Sara Wacklin , writer , Kjell Westo , author , Henrik Tikkanen , author , Marta Tikkanen , aurthor , Solveig von Schoultz , poet , etc .

I hope that this will clarify my opinion better .

Thank you .

Nihad A. Rasheed