A door to the other side

7 September 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Building bird-houses is author Jyrki Vainonen’s hobby: he has crafted dozens of nesting boxes and hung them on trees for winged tenants. Roaming in the woods may be bring surprises, though: the bird-house man suddenly finds the world underfoot opening up or a moment… An extract from the collection of stories Linnunpöntön rakentaja (‘Builder of bird-houses’, Atena, 2012)

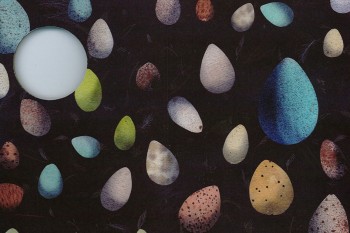

Birds coming up… Inside front cover of Linnunpöntön rakentaja by Elina Warsta/Solmu

The hinge was rusty, but after a cleaning and oiling it seemed to work, and didn’t even squeak. I had found it in a piece of board that was lying beside the road on the way to the dump. The board may have once served as part of a door frame.

The next day I rode my bike there again and unscrewed the hinge from the board, and now it looked quite handsome attached to the side wall of the birdhouse. I set the still floorless, roofless box upright and tried the door, opening the clasp and lifting the side wall on its hinges. It worked well, didn’t jam or make any sound. Next I attached the pieces of wood I’d already cut to form the roof and floor of the birdhouse. I inserted the floor and nailed through the three walls of the box – all except the wall that formed the door. Then I nailed the roof in place with several nails.

Now I had a box that would make it easy to watch the life inside. It would doubtless be wonderful to be able to see the nest from so close, and from the side rather than the top, as I usually had before. I could take photos, too.

I took the hinged birdhouse straight to the woods. It was the middle of April, not long before Easter. I had found a place for my creation in a hollow in an old spruce grove. I’d drilled a hole less than three-centimetre wide in the front of the box. I imagined that a crested tit or a spruce tit might move in. The blue tit, the third possibility, was at that time, in the 1970s, still so rare in Southeast Finland that I didn’t dare to dream of one making its nest there. And the spruce woods probably wouldn’t tempt a blue tit, since according to my bird book they preferred the rustle of leafy trees to the soughing of spruce, and thus particularly enjoyed Finland’s Southwest corner.

When I got to the woods I attached the box to the trunk of a youngish spruce with a piece of wire. The spot was secluded, and the box could only be seen from one direction, and only from a few meters away.

I went to visit the place regularly. On my third visit after May Day, I could tell from a long way off that some kind of tit had found the box, because I could see a bit of hair and fluff in the mouth of the opening. I felt a splash of joy in my chest. I hurried over to it, opened the clasp, and lifted the wall carefully, because the mother bird might already be sitting on the nest and be startled when the wall suddenly opened up beside her.

But there was no one there. The structure of the nest was clearly visible: a few layers of moss on the bottom of the box with a cup made of hair and fluff built on top. All of this was covered with another layer of hair, from which I gathered that she was in the middle of laying her eggs. The mother bird must have come to lay an egg that morning and then covered it up. The incubation wouldn’t start until all of the eggs were laid.

I closed the wall and threaded the clasp back into place. It was impossible to know which kind of tit had built the nest. It wasn’t a great tit, in any case, because the hole in the box was too small. I went a distance away to a good observation point. Perhaps the idea of waiting was a bad one, since the mother bird probably wouldn’t return to the nest until the following morning to add another egg, but I decided to try anyway.

I crouched among the spruce saplings and enjoyed the beauty of the spring woods. The damp, marshy hollow rang with bird song. I recognised some of the songs – a redwing, a robin, and a bullfinch. I could hear a chaffinch farther off as well. The moist bed of moss under the trees was pungent with fragrance. The uneventful wait made my mind slip into a kind of borderland between the conscious and the subconscious. I experienced what many of my forefathers had experienced before me when roaming in the woods: I stared at the tree so unceasingly and intently that I started to see through it – and the world underneath opened up to me, the place where the forest beings live their lives. Behind one fir tree lurked something or someone: an elf, a forest sprite? I fastened my eyes on two fairy creatures, elves or gnomes, in a nearby thicket: one, keikas, sullen and hairy, with only one arm or leg, an ugly, growling thing; the other, männinkäinen, friend to witches and protector of ants. (A sprightly parade of ants formed a highway at the root of the birdhouse tree leading to an anthill that lay behind it.) Did I hear a murmur and a whisper, or did I imagine it? Did someone titter? Who made that tree limb sway? The gateway to the hidden world closed, however, when a movement brought me back to the reality of my senses: a bird had slipped into the top of the spruce tree.

I thought it had seen me crouched among the saplings. I stood up suddenly so that I could hear its warning cry. The winged thing flitted among the branches, descending a little at a time. Then it disappeared.

It didn’t make a sound. If it was the inhabitant of the birdhouse, it had to be a spruce tit. A crested tit, tufted head, is such a feisty, lively thing that it would have been indignant and sounded the alarm to the rest of the forest dwellers the moment it sensed my presence. A spruce tit, on the other hand, is the quietest, most secretive of the nesting tits, particularly at egg laying time. There had also been lots of cones in the spruces that winter. In a good spruce cone year there are usually a lot of spruce tits, and nesting goes well. I left, filled with impatience.

The mystery of the box’s inhabitants was solved on my next visit. When I opened the hinged wall, I saw a spruce tit up close, sitting in the box staring at me, almost entirely buried in the fluff of the nest. All I could actually see of it were the tip of its tail and its head, with two black eyes shining out at the gigantic intruder. I felt like Gulliver peeking into the Lilliputians’ palace, moved and amazed at what I saw.

I watched the pair of spruce tits all that summer. Eight chicks left the nest for the wider world. One of the ten eggs didn’t hatch, and one was trampled to death by its siblings. I found it later in the fall, a dried mummy among the ruins of the nest. The mummified body of the little bird made me, a young person, understand for the first time that I, too, would die some day.

I remembered that flash when I saw the forest beings. I thought the fairy creatures had taken the birdhouse under their protection. So I wasn’t shocked when one day I thought I saw a swamp troll, with its long, black hair, green skin, and clothes made of moss, crouched at the foot of the birdhouse tree next to the anthill. It must have got lost, because swamp trolls lived in swamps, didn’t they? When the scary-looking creature heard me approach, it slinked away without a sound. But there were web-footed tracks left in the carpet of moss, with four toes on each one. Too bad I didn’t have a camera with me. Or would it be impossible to immortalise those tracks on film?

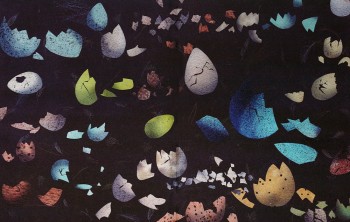

Inside back cover: Elina Warsta/Solmu

When I went to look at the birdhouse the following May, it was gone. Apparently a birdhouse with a hinged wall was such a fine thing that somebody stole it.

I couldn’t think of any other reason for its disappearance. Hopefully many more broods have grown up in the box, wherever it happened to be after it was ‘transferred’ – perhaps somewhere in the land of the swamp trolls, on the side of a snag deep beneath the cushion of peat.

Translated by Lola Rogers

Tags: Finnish nature

No comments for this entry yet