The magic box: childhood revisited

25 December 2014 | Essays, Non-fiction

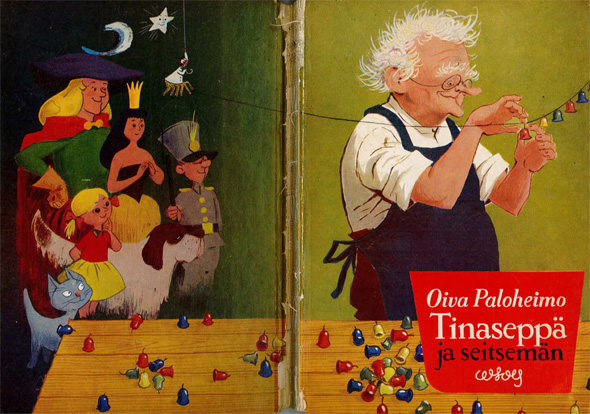

The tin soldier and the Blue Cat. Illustration: Usko Laukkanen

A tribute to Oiva Paloheimo’s children’s novel Tinaseppä ja seitsemän (‘The Tinsmith and the Seven’, illustrated by Usko Laukkanen, WSOY, 1956)

I’ve happened upon this (Christmassy) text of mine – first published in Books from Finland back in 1995 – when sorting through my papers as I begin to contemplate my retirement. With it I would like to offer my goodbyes, and many thanks, to you – to our readers, for whom I have been commissioning, editing and writing texts for the past thirty-one years – it’s time to do other things; time to read the books that still remain unread…

A dusky winter’s afternoon. Outside, soft and grey, a little snow is falling. I am sitting in our living-room, in an armchair covered in a pale yellow boucle fabric, my legs curled up, eating a carrot. In my lap is a book which I have fetched from the library after school. Conversation, the faint clattering of crockery, a singing kettle, the smell of food: grandmother and mother are cooking supper in the kitchen. My little sister is asleep.

But these sounds and the room around me do not really exist: there is only the world of make-believe in which Tiina sets off on her adventures with the Blue Cat, the Tinsmith, the St Bernard dog, the star and the spider: that world is a magic box which is able to contain all of childhood.

In his fascinating book of memoirs, Laterna Magica, the Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman presents an astonishingly exact visual memory of a time when he was less than two years old: the appearance and colour of the kitchen tablecloth and of his porridge bowl (the moment before he was sick into it).

To tell the truth, I do not really remember a scene described above, even though at that time I must have been about nine. But the reconstruction is easy, and historically reasonably believable, too: a glance at Oiva Paloheimo’s children’s book Tinaseppä ja seitsemän (‘The Tinsmith and the Seven’) immediately takes me back to ca. 1960. I used to spen hours on end in that fashionably teak-legged boucle chair in our new, one-bedroom rented apartment in a Helsinki suburb – and I could have been reading exactly that book, for it made an indelible impression upon me.

I never owned the book, but some years ago it began to come to mind with a strange insistence, so I began to look for it in Helsinki’s second-hand bookshops. Time passed, but the book was nowhere to be found. Then, one day, I found it in a second-hand bookshop next door – and the owner gave it to me for free, because the spine was missing!

I never owned the book, but some years ago it began to come to mind with a strange insistence, so I began to look for it in Helsinki’s second-hand bookshops. Time passed, but the book was nowhere to be found. Then, one day, I found it in a second-hand bookshop next door – and the owner gave it to me for free, because the spine was missing!

And the magic box opened at once. I remembered all Usko Laukkanen’s warmly humorous, succulent black-and-white line drawings. I had forgotten the details of the plot, but I remembered the story: just before Christmas, a poor tinsmith uses the last of his supplies of tin to cast Christmas bells in order to buy food, but because, sadly, his bells do not ring, no one buys them. But because of the miracle of Christmas, out of the tin seven creatures are born: a little girl, Tiina; a St Bernard, Duke (for whom the most important thing in life is food); a prince and a princess (who bring romance and adventure to the story); a tin soldier, Gustavus Inch; a star, which looks after lighting and various tasks of guidance, and Mr S. Spider, a real 1950s information engineer. Its job is to create radio contact, through a net it constructs in a corner of the ceiling, with wherever the plot of the story demands – and even transmit people from one place to another electronically.

Paloheimo writes mischievously and humorously, and for adult readers as well as children. The Blue Cat, which is discovered in a snowdrift on Christmas Eve and becomes the story’s prime mover, its deus ex machina, resourcefully arranges everyone else’s affairs and succeeds in securing for the impoverished Tinsmith an amazing, frightening fortune.

But what to do with the money, after a bone has been bought for Duke the dog, and a new school satchel for Tiina? ‘The Tinsmith suggested that a thousand million should be given to the state. The state could then distribute the money to sick and poor citizens. The idea was considered worth mulling over, and it was resolved to find out the state’s address. For it was necessary first to ask whether the state was at all prepared to go to the trouble of helping citizens who were in need of assistance.’

Gustavus Inch, the tin soldier, comments that there is no point in giving money for the cause of peace, for it would immediately be used to buy guns. ‘War cannot be held in check without guns. And peace cannot be financed in any way, for peace is the result of goodwill.’ Not shrinking from the naïvely innocent racism of the day, Paloheimo has Gustavus Inch suggest that all the negroes of Africa should be bought mouth-organs to amuse them and thus stop them boiling ‘honest Finnish soldiers’ alive in their pots: ‘negroes have such good lips for mouth-organs’.

Oiva Paloheimo (1910–1973) is best-known as a writer for a completely different children’s book. Tirlittan (1953) is a slightly sombre story of an orphan girl who loses her home in a fire; Tirlittan plays her ocarina and wanders the world alone. Tinaseppä has long since been sold out and forgotten.

Paloheimo, according to the biography written by his son, the poet Matti Paloheimo, was the grasshopper figure from the fable of the ant and the grasshopper: a lovable, kind-hearted hedonist who had children and wives and women friends and alcohol problems, but less often money or the energy to shoulder life’s responsibilities. He wrote prolifically and rapidly, novels, short stories, poems, articles, children’s books. Today, most people associate his name only with Tirlittan, and perhaps with his autobiographical novel Levoton lapsuus (‘A restless childhood’, 1942).

At the end of the Tinsmith adventure, the prince and princess are united and all ends in a wedding and general rejoicing: ‘S. Spider became so excited that it left its web and its antennae and its microphone and leaped into the centre of the room. It began to dance like a maniac, with all its legs; it danced all the wedding dances, which it had learned over millions of years.’ Tiina and the Tinsmith go on living in their idyll, but Gustavus Inch is attracted by war as if by a magnet, while the Blue Cat is driven by longing, so that both of them set out to wander through the world.

The Blue Cat says to Tiina: ‘Life is a fairytale, my dear, if only you know how to create it in the right way, with innocence and love. And the story of life is as long as longing, longing from happiness to happiness, from day to day, until the last sunset.’

Enchanted: a young reader. Photo: Kalervo Lehtonen (ca 1956)

Tinaseppä ja seitsemän is, for me, as an object, more than a 1950s fairytale: it is the magic box of childhood. Perhaps all those who have, as children, had a close relationship with books and their illustrations remember their favourite books as symbols that are deeply impressed on their minds.

A familiar picture is not just Seamus the sailor dog’s grass-lined bunk, in which Seamus sleeps happily, his white belly hairs as soft-looking as the green grass, but something more – the green of the grass is a room, decades ago, the patterns on the carpet, the smoothness of the arms of a rocking chair, a bird-cage on top of a kitchen cupboard, the smell of a plantain in the yard, the music played by an itinerant accordionist; it is always a sunny afternoon in a street that is paved with diagonal yellow stones, decorated with the cool shadows of lime trees.

It is something that cannot be apprehended, because it flees, something that cannot be completely described, because it is not whole, and something that cannot be shared with anyone else, because it is only your own.

When you open the book, you open the box and look inside: even if there is nothing definite there, it is full of experience without form, it is the after-image of enchanting moments of childhood – and it is always a delightful experience, always.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

This is a slightly edited version of the text published in Books from Finland 4/1995

Tags: children's books, illustration

1 comment:

26 December 2014 on 3:38 am

Thanks, Soila, for reprinting this lovely essay. There is nothing quite like the experience of opening a book not seen since childhood and being immediately immersed in the same wonder you felt years before.

And thanks for all your years editing Books from Finland. It’s impossible to overestimate how much it’s meant to me and to so many other friends of Finnish literature.

Merry Christmas!