Author: Pekka Tarkka

Delirium into art

Issue 4/1991 | Archives online, Authors

Sometimes with fury, sometimes with delight, the Finnish reading public has followed Hannu Salama’s career with unflagging interest for almost 30 years. For the past ten years, the author has let it be known that he has been working on a novel about the Finnish traitor Otto Wille Kuusinen, a henchman of Stalin entrusted with high office in the Kremlin, who managed to survive the worst years of his mentor’s terror.

Ottopoika (‘Otto the adopted’, 1991) is a disappointment in that it is not, in fact, a political novel about the chameleon-like Kuusinen, but rather a story about a Finnish writer, Risto Mikkola, Hannu Salama’s alter ego, whose intention it is to write a book about Kuusinen. Neither is this Mikkola a Kremlinologist of any description, but, patently, a prisoner of his upbringing: he spent his childhood among the proletariat of Tampere, an industrial city in central Finland sometimes known as the Manchester of Finland, whose suburb, Pispala, was a hotbed of Finnish communism. More…

How to survive in the fast lane

Issue 2/1991 | Archives online, Authors

Kjell Westö is very young, but he has enough historical sensibility to be able to understand small details and how they vary as epochs change. Reading him, I was reminded of one of the dustiest practitioners of the philosophy of art, the 19th-century Hippolyte Taine.

Taine was a dyed-in-the-wool positivist who sought connections between art and geology: just as the earth is overlaid with a layer of ‘soft mulch’ – last year’s decomposing leaves – so ‘the individual is overlaid with customs, ideals, spiritual or intellectual characteristics which last for three or four years; they are the creations of fashion and the moment’; among them are details of speech and clothing. Taine’s description, written around 1830, of the young literary hero, is unforgettable: the upstart ‘who has great passions and deep dreams, who is inspiring and lyrical, political and rebellious, humanitarian and reformist and enthusiastically consumptive, fateful looking with his tragic waistcoats and his arresting hair style’. More…

Writers from Pispala, the Red citadel: Lauri Viita and Hannu Salama

Issue 4/1988 | Archives online, Authors

Pispala is a Tampere suburb of some 7,000 inhabitants which has produced two top-class writers, Lauri Viita and Hannu Salama, as well as many others. In Finland it has the same kind of legendary status as London’s Bloomsbury, but how different it is from Bloomsbury!

No university, no museums, no old patrician mansions. Its little wooden houses are built higgledy-piggledy on a high moraine ridge from which a magnificent view opens out over two lakes and the river valley between them, where the chimneys of Tampere’s machine works, textile factories and paper mills rise. Pispala’s inhabitants have traditionally been factory workers whose contact with acting and literature has come through working men’s associations, sports clubs and local settlement houses. How is it that such surroundings gave rise to the birth of real literature? More…

The Nobel pursuit

Issue 2/1988 | Archives online, Authors

The award of the Nobel Prize for literature is always a combination of political expediency and literary judgement. The events leading up to the award of the prize to F.E. Sillanpää (1888–1964) tell us a great deal about successful strategies in the game called ‘How to win your Nobel Prize’.

At the beginning of the Thirties Sillanpää had the approval of Sweden’s literary public behind him, since translations of his early works – a large number of the important short stories he wrote during the 1920s as well as his novel Hurskas kurjuus (1919; English translation Meek Heritage, 1938) – had been very well received in Sweden. Sillanpää had many friends among Finland’s western neighbours and his robust and impressive figure was well known in the literary salons of Stockholm. More…

Too much or too little love

Issue 1/1987 | Archives online, Authors, Reviews

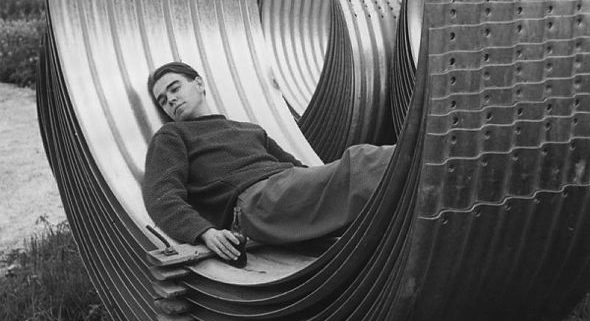

Rosa Liksom. Photo: Pekka Mustonen.

On the October day last year on which Rosa Liksom‘s second collection of short stories, Unohdettu vartti (‘The forgotten quarter’), was published, she also opened an art exhibition of her own work. The occasion took the form of a kind of cross between performance art and a practical joke. Young women dressed in Finnish military uniforms carried out body searches on every newcomer, changed the guard and drilled, while crackers exploded in the gallery. Many people were of the opinion that it was all no more than a silly joke. Even the art critics were not enthusiastic: they felt that Rosa Liksom’s felt pen work was derivative of a certain Danish artist who himself had copied the cartoon-like stick-men of the so-called Chicago school. But all the same, there emerged from the pictures a funny story about the artist’s adventures among the underground youth of Russia from Leningrad to Vladivostock.

Only her closest friends knew which of the soldiers in the gallery was Rosa Liksom, which her clones. Rosa Liksom is a pseudonym, and her little game of hide and seek has already lasted a couple of years. We know of her that she was born in Lapland, studied anthropology, has travelled in both East and West and lived for a long time in Copenhagen. Her writing was published for the first time in an anthology of the work of young authors, Kalenteri 84 (‘Calendar 84’, 1984). Her first work, the short story collection Yhden yön pysäkki (‘One-night stand’) was published in 1985 and achieved considerable success. More…

Reality versus morality

Issue 3/1982 | Archives online, Authors

Eila Pennanen. Photo: Anonymous (Suomen Kuvalehti 1965) via Wikimedia Commons

Reviewing Eila Pennanen‘s second collection of essays, which appeared earlier this year under the delightfully ambiguous title of Kirjailijatar ja hänen miehensä (‘The authoress and her… man? … men? … husband?… husbands?’), a critic called attention to the heading she had chosen for her essay on Bernard Malamud: ‘Malamud’s ignoble hero’. His comment on this was that the moral judgment implicit in such a title would be both pointless and valueless if Pennanen had maintained it with logical consistency throughout the essay. If in fact she does no such thing, it is because she knows how to look at a character, however ignoble, with an eye for subtleties and a great deal of psychological insight. This is something one often notices about Eila Pennanen: she is apt to begin by labelling somebody or something ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and even to sound quite defiant about it, but she is never, in the end, content to leave it at that. I once heard her give a lecture on Joel Lehtonen. She startled her audience by the vehemence with which she avowed the feelings of loathing or sympathy aroused in her by characters or events in Lehtonen’s books. Her cheeks blazed as she talked. Then, just as unexpectedly, she chided herself for exaggerating, took back a lot of what she had said, laid bare the reasons for Lehtonen’s contradictoriness, and left her hearers in a condition of fruitful perplexity. Whatever they may have thought or felt about the ‘moral approach’ to criticism, they were left in no doubt as to the wit and intelligence of its leading Finnish exponent. More…

Pekka Tarkka on Antti Tuuri

Issue 2/1981 | Archives online, Authors

Antti Tuuri. Photo: Jouni Harala

A character in one of Antti Tuuri’s short stories, a German engineer, remarks: “It has always seemed to me that the Finnish language doesn’t contain individual words – it is just an effusion from a state of mind.” The quotation is taken out of context but it serves as a good description of the slow and sentimental or atmospheric tradition of prose style developed by a number of Finnish writers. This is a category which does not include Antti Tuuri (born 1944). His prose is crisp, clear and concrete in the Indo-European manner. It is not in the least ‘an effusion from a state of mind.’ He uses ‘individual words’ precisely, concrete observations, descriptions of specific phenomena; it is not rare to find numerals in his text.

Tuuri’s style undoubtedly owes something to his training and background. He qualified as an engineer and has worked in a number of posts requiring a high level of technical skill and business ability: he was technical supervisor in a newsprint works and in a wallpaper factory, he has sold Finnish printing equipment abroad and has trained engineers in his field. When Tuuri became Chairman of the Union of Finnish Writers in 1980 he brought to the Union’s administration the modern and professional management techniques that are characteristic of his approach. More…

On Arto Melleri

Issue 1/1981 | Archives online, Authors

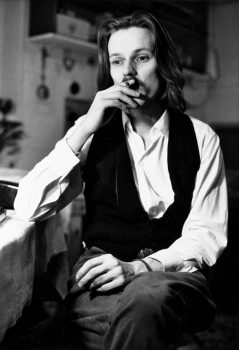

Arto Melleri, 1982. Photo: Pekka Turunen.

Arto Melleri (born 1956) is an experimenter, and, though still young, has lready explored a vanety of forms. He made an unusual start by writing, early in the 1970s, for a series called Kontakti-kirjat (‘Contact Books’): these were intended for a teenage audience and consisted of short stories and confessions written by young people. It is possible Melleri now feels some embarrassment at this debut. It did, however, get him off to an early start in poetry, and his first volume, Slaageriseppele (‘A bouquet of hit-tunes’, 1978) contains a faintly nostalgic piece about a teenage boy who churns out poems for the local newspaper in Ostrobothnia and collects his pittance for them.

Melleri is also involved in the theatre. He has studied at the Finnish School of Drama, and worked as dramaturg in the Finnish Radio Theatre. Together with Jukka Asikainen and Heikki Vuento, he wrote the script of the play Pete Q, which was a big hit in the summer of 1978, when it was performed by a scratch fringe group of actors bored with the conventional theatre with some gifted young drama students, and directed by the talented young Arto af Hällström. It is an avant-garde play, cutting through the current theatrical shibboleths, and establishing the point of view of the new theatrical generation. More…

On Daniel Katz

Issue 4/1980 | Archives online, Authors

Daniel Katz. Photo: Veikko Somerpuro/WSOY.

Daniel Katz (born 1938) is a member of Finland’s small Jewish community and the first Finnish writer to emerge from that background. The publication of his first book coincided roughly with the appearance in America of a wealth of Jewish literature. Katz has much in common with American Jewish writers, particularly in his parodies of conventional religious practices, but the Jewish community he writes about relates to the general social environment in a very different way. Writers like Philip Roth are concerned with a social group that is tightly hemmed in by its own claustrophobic boundaries, whereas Katz’s Jews, living alongside the reserved and at times withdrawn Finns, stand out as exceptionally extroverted and sociable beings; their Jewishness is not a fetter but their innate key to freedom. More…

On Markku Lahtela

Issue 3/1979 | Archives online, Authors

Markku Lahtela is one of the more colourful personages on the Finnish literary scene. He studied at the universities of Moscow and Munich, served on the editorial staff of an encyclopedia, published his first book in 1964, and proclaimed that his favourite writer was Anatole France. The powerful radical currents of the 1960s took him out into the streets as a demonstrator: he wrote scripts for a theatre group that went in for staging ‘happenings’, took part in politics as the enfant terrible of the Centre Party, publicly burnt his military passbook, translated Herbert Marcuse, and became an enthusiast for the anti-authoritarian educational experiments of A. S. Neill and his followers. Out of these restless years came two long, highly personal and very uneven novels, Se (‘It’, 1966) and Yksinäinen mies (‘The solitary man’, 1976), in which Lahtela is primarily concerned with a young man’s difficult family relationships, and seeks to demonstrate his fundamental honesty by recourse to automatic writing. Early in the 1970s he published three short collections of philosophical observations and stories. These, the fruit of wide but indiscriminate reading, amounted to little more than the compilations of an amateur, the basic idea being to demonstrate, by means of biological and psycho-analytical arguments, the primacy of the mother-child relationship among the factors affecting a human being’s development. More…

On Erno Paasilinna

Issue 4/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Erno Paasilinna. Photo: Irmeli Jung

In one of his essays Erno Paasilinna speaks of a modern phenomenon, the ‘quasi-author’. A quasi-author is the kind of literary buff who writes for the papers, takes part in congresses, sits in panels and appears frequently on television. Wherever there is controversy, be it over the function of the President, the legality of strikes, the abortion laws, the evangelical movement or the present state of lyric poetry, the quasi-author is invariably to be found. Paasilinna atones for his irony by freely admitting that he is himself a typical specimen of the breed.

For the concept of the quasi-author Paasilinna refers us back to Ilya Ehrenburg, who noted in his memoirs that the profession of authorship had been undergoing a steady diminution of social and political influence ever since the early 30s. Since Ehrenburg’s day the process has accelerated: television, efficient communications, and the ceaseless output of ‘information’ by what amounts to a major modern industry, have finally toppled the novelist from the throne he successfully occupied for so long. The quasi-author has replaced him, availing himself of all the new media in the hope of achieving a more rapid and direct impact on the public – and perhaps also of preserving the traditional influence of the writing fraternity. Erno Paasilinna was born in 1935 near Petsamo (now Pechenga) on the Arctic coast: from 1922 till 1944 this region was part of Finland. Evacuated during the upheavals of the Second World War, the family was forced to lead the nomadic life of refugees, wandering across the Arctic wastes as far as Norway before they were able to find a settled home in Finland. Erno Paasilinna has not rejected the landscape or the traditions of his native area: he has edited four anthologies of extracts from early accounts of travel in Lapland. It was in Northern Finland, too, that Paasilinna completed his education (he attended the Lapland College of Further Education) and began his writing career. More…

On Alpo Ruuth

Issue 3/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Alpo Ruuth. Photo: Sakari Majantie / Tammi

Alpo Ruuth (born 1943) grew up in Sörnäinen, a working-class quarter of Helsinki, amid dirty grey tenements, railway goods yards, machine shops, timber yards and slaughterhouses; a district reeking of rust and dust, of gasometers, steam locomotives, pinewood, toad-in-the-hole and roasting coffee. Ruuth completed three years of secondary schooling and then decided that he had had enough. He worked as a garage hand, a shoemaker, a casual labourer, a salesman and a storekeeper. The publication of his first novel, Naimisiin (‘Getting married’, Tammi, 1967) set him free to adopt writing as a career.

Ruuth first became known to a wider public through his novel Kämppä (‘The commune’, Tammi, 1969 ). This describes the adolescent years of a group of Sörnäinen boys who live like a tribe of savages in this urban jungle. They establish a commune of their own, cut off completely from the adult world, and rely on a process of trial and error to teach them how to live. The charm of the book comes from the spontaneity and quick reactions of these teen-age youngsters: chattering, mimicking, footballing or fornicating, they are all the time as alert as puppies, while the life of the city around them goes on ‘for real’. The final section of Kämppä describes how they eventually slot themselves into the community. Most of them accept their fetters with resignation, but there is one – the chief character of the novel – who strives to maintain his critical attitude to the values which dominate his surroundings, and to live up to it in practice. Some of Ruuth’s finest writing in this novel is devoted to the harmonious family background of this young man’s early years. He seems to be saying that ethically valid solutions to life’s problems grow out of the personal relationships of early childhood. More…

On Matti Pulkkinen

Issue 2/1978 | Archives online, Authors

Matti Pulkkinen. Photo: Gummerus

Matti Pulkkinen’s grandfather was born in 1842 in a forest village close to the Russian border, in an area which could only be reached by water. When he grew up he became a tar-burner, a traditional occupation in north-east Finland. Pulkkinen’s father worked for the Otava Publishing Company in the early years of the present century, a time when ordinary Finns were beginning to show a real interest in literature. In his home in one of the most remote parts of North Karelia, he assembled a library which ranged from Mark Twain to the detective stories of G. K. Chesterton. He was 70 when his youngest son, Matti, was born in 1944. Dostoyevsky and Nietzsche were the two writers whose works did most to stimulate Matti Pulkkinen’s enthusiasm for literature. After leaving school he set out to see the world. He worked as a lumberjack, a primary school teacher, a statistics clerk in a gynaecological hospital, a bank teller, an accounts clerk, and later as a carpenter, took part in the restoration of the medieval church at Vanaja. From 1969 to 1971 Pulkkinen worked as a nurse in mental hospitals in Frankfurt, West Berlin and Bern. While in Switzerland he became interested in Jungian psychology and modern group therapy.

Pulkkinen’s novel, Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’, Gummerus), published in 1977, was awarded the J.H. Erkko Prize for the best first novel of the year and the Kalevi Jäntti Memorial Prize. It rapidly became a best seller and has already had two reprints. More…

On Pentti Saarikoski

Issue 4/1977 | Archives online, Authors

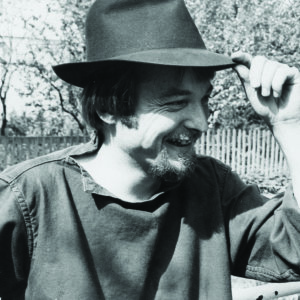

Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983). Photo: Markku Rautonen / Otava

Born in 1937, Pentti Saarikoski was one of the many Finnish children who were evacuated to safety in Sweden during the Second World War. For almost twenty years – 1958–1975 – he had a sensational career as the enfant terrible of the new wave of post-war Finnish verse and as a translator of classical Greek poetry. Now Saarikoski is once more in Sweden, where he lives in a kind of spiritual and intellectual exile. The vast scope of Saarikoski’s work as a translator reveals the breadth of his interests and poetic skill. Among his translations into Finnish are works by Aristotle, Euripides, Sappho, Theophrastus, Xenophon and Homer’s Odyssey (a free verse translation that has been particularly praised for the freshness it brings to the work). Saarikoski’s translations of J. D. Salinger and Henry Miller have introduced modern urban slang into Finnish literature, and together with his brilliant translation of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1964) epitomise the catholicity of his interests. Saarikoski’s first poems were written in the spirit of ‘Finnish Modernism’: short poems, pleasing in their treatment of language, subtly erotic and ironic, drawing their strength from a fleeting image, metaphor or momentary fancy. Early in the 1960s, Saarikoski emerged from his scholarly retreat. He became a favourite of the yellow press and of television, he was held in the awe normally reserved in other parts of the world for royalty and pop stars. He loved this publicity and the scandal he deliberately created: he saw his function as to provoke the youth of the day to reject established ideas of authority and morality. He further outraged the middle classes (into which he himself was born) by joining the Communist Party.

More…

-

About the author

Pekka Tarkka (born 1934) is an author and literary critic. Among his works are an extensive biography of the poet and writer Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) and of the author Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934; first volume, 2009; the second volume, 2012).

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.