Experiments with reality

Issue 3/1985 | Archives online, Authors

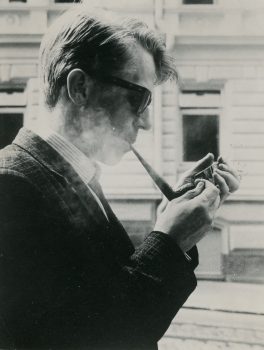

Väinö Kirstinä. Photo: SKS Archives

Väino Kirstinä (born 1936) regards himself as a member of the ‘second generation’ of Finnish modernists. His first collection of poems, Lakeus (‘The plain’) was published in 1961, followed two years later by Hitaat auringot (‘Slow suns’) and, the same year, by the work that gained him public recognition, Puhetta (‘Talk’). In 1979 Kirstinä commented on the aims of Puhetta: ‘the work … aimed to break the mould of Finnish modernism in some senses – hermetics, for example. I tried to bring everyday language into poetry – trams and fridges alongside the familiar symbols of mountains, lakes, beaches and birds. My poetry opened up, it developed into a kind of unclean lyricism.’

His interest in words as one of the constituents of poetry is characteristic of Kirstinä’s work, as is his search for the sources of modern poetry, such as the work of Baudelaire, which he has translated into Finnish, and the later tradition of surrealism and dada, which is clearly influential in his extensive collections Luonnollinen tanssi (‘Naturaldance’, 1965) and Pitkän tähtäyksen LSD-suunnitelma (‘Long-term LSD plan’, 1967).

Luonnollinen tanssi embraces a wonderfully wide range of elements. Its dadaist lack of restraint was almost unheard of in the Finnish poetic world of twenty years ago; in fact, to find a precursor one has to go to the Finland-Swedish modernism of the inter-war period (for instance, the work of Gunnar Björling). The social awareness characteristic of the 1960s is evident in the long series Atomipompotusta (‘Atom junk etings’), which is dedicated to the pacifist committee called Sadankomitea. Unlike many of his contemporaries, however, Kirstinä did not become primarily a political poet, perhaps because words and the literary tradition interested him more than ideology.

Luonnollinen tanssi and Pitkän tähtäyksen LSD-suunnitelma are among the most typically characteristic of the Finnish poetry of the 1960s; today, together with the work of Kirstinä’s contemporary Pentti Saarikoski, they are regarded as classics. Kirstinä took over the language of modern technological, urbanised and cosmopolitan society, in fact the entire world of consumer durables that the new welfare state of Finland was so eager to grasp.

Kirstinä’s sixth collection, Talo maalla (‘A house in the country’) was published in 1969 and foreshadowed with extraordinary accuracy the shift in preoccupation of Finnish poetry from society to environment. The collection was, significantly, dedicated to ecological action groups; nature, its preservation and pollution, became the driving concern of the Finnish poetry of the 1970s, in contrast to the urbanity and politics of the previous decade. Typically for its time, the collection reflects an almost apocalyptic atmosphere; its attitude is one of resignation, in places despair. The central work of this new phase in Kirstinä’s poetry is Säännöstelty eutanasia (‘Rationed euthanasia’, 1973), in which the very same society that was the butt of so many jibes during the 1960s has started to threaten the individual and to develop towards totalitarianism and authoritarianism, an engine controlled by machines and technocrats.

At the same time Kirstinä’s poetry has moved closer to the mainstream of Finnish modernism, in which the experience of nature and the apparent limitations of everyday life have always been important. Kirstinä now defends the poet’s right to a relative freedom, to be able to write without asking ‘Why? What is the goal?’ Does this right also define the poet’s duty toward his work? In one of the poems of his latest collection, Hiljaisuudesta (‘On silence’,1984), Kirstinä writes: ‘Internal resistance/springs from the sharpness of the senses.’ From his beginnings in the constructivist literary tradition of the 1960s, Kirstinä has come to emphasise his own perception and experience, the meaning of ‘direct’ encounter with reality. The existence of the internal resistance of which he writes can clearly be seen in Kirstinä’s latest works: the difference is merely that its expression has become simpler.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Pertti Lassila

The heart of reality - 30 June 2007

Grasping reality - 30 September 2006

Mortal song - 30 December 2005

What makes a classic? - 31 March 2004

-

About the writer

Pertti Lassila (born 1949) is a literary scholar, writer and critic.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.