Boys Own, Girls Own? –

Gender, sex and identity

30 December 2008 | Essays, Non-fiction

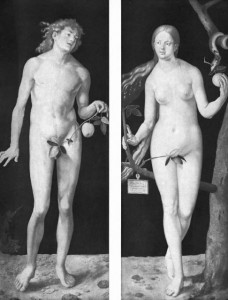

Knowing good and evil: Adam and Eve (Albrecht Dürer, 1507)

In Finnish fiction of the present decade, both in poetry and in prose, there seems to be at least one principle that cuts across all genres: an overt expression of gender, writes the critic Mervi Kantokorpi in her essay

Relationships and family have always been central concerns of literature; questions about gender and individual identity have received a new emphasis in Finnish literature from one season to the next. The gender roles represented in contemporary literature appear to become ever more stereotypical. The question is no longer only of the author consciously setting his or her gender up as the starting point for expression, as has already long been the case with modern literature written by women. Practices that gender and express differences are much broader and more fundamental; even when a text seems to be consicously breaking down gender clichés – the masculine man and the feminine woman – differentiation between the genders is still emphasised.

For example, in her new satirical novel Kohtuuttomuus (‘Excess’, Siltala, 2008) the dramatist and prose writer Pirkko Saisio (born 1949) depicts man as a soft and yielding feminine being, and woman as a strong-willed and powerful being who is comparable in working ability to more than one man; this superwoman has also spoilt generation after generation of men through her child-rearing.

If you stop for a moment at any Finnish backwater pub or TravelCare bar (travelling has diminished, but the care’s still there), you may notice that over time the Finnish man becomes a granny clothed in a shell suit. The facial features are fragile, the voice is shrill, the beard growth nonexistent and the body language minimalist. On the other hand, the Finnish woman may be found – in the same backwater that is – collecting mushrooms or berries in the same kind of colourful shell suit, while her husband sits in the pub, and she’s got a mobile phone on her belt and a farm co-op or Shell cap on her head.

The Finnish woman knows how to navigate the woods, split logs, change light bulbs, raise children alone, fill out an agricultural subsidy application, drive a car, vote, defend a dissertation and hold her own in panel discussions, divorce property division proceedings and municipal councils. What does the Finnish woman need a man for?

There seems to be some sort of overarching, essentialist thought pattern in the literary presentation of gender; that is, the essential characteristics of a woman and a man can be defined just as easily for any person. The reception of literature has also regarded that hegemony of the genders critically, not least because contemporary prose that revolves around relationships and sex is what most often ends up on the best seller lists – for example the blithe novel Ei kiitos (‘No thanks’, Otava, 2008) by author, actress and columnist Anna-Leena Härkönen (born 1965). It is a frank tale of a rebellious wife who’s not getting any from her reluctant husband. Härkönen’s idea isn’t new of course: the motives of the sexually unfulfilled woman have been considered repeatedly in the Finnish ‘strong women’ literature since Maria Jotuni wrote her unconventional comedies and novels during the first half of the 20th century, and which have since become classics.

Literature emphasising gender thus encompasses a very diverse set of projects: on the one hand, serious social analyses of identity and power, and on the other, projecs like those of Härkönen, a social butterfly participating in the popular public talk of our sexualised age.

The prose currently written by middle-aged male Finnish authors has been repeatedly called äijäkirjallisuus: the term, could perhaps translate as ‘bloke-lit’, refers to books that are ‘Boys Own’, and are masculine narratives with generally short sentences and a realistic style. This has referred just as much to the prose output of Kari Hotakainen, Jari Tervo, Hannu Raittila, Juha Seppälä, and Petri Tamminen (born 1957, 1959, 1956, 1956 and 1966) as to that of many other authors who are seen as writing about a world experienced as masculine. The great Finnish portrayals of men, the ur-novels, Aleksis Kivi’s Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers, 1870) and Väinö Linna’s controversial war novel Tuntematon sotilas (The Unknown Soldier, 1955) loom in the background in this äijäkirjallisuus. Man, or a homosocial group of men, operates outside the carefully regulated domestic sphere represented by women and share the experience of ostensible freedom and outsiderness. These ‘men of the woods’ (an old, romantic-heroic appellation for the free, masculine, survivalist Finnish male) do the deeds of men and attempt to get along with women. Modern, urban nuclear family-centric life oppresses the man longing for the lost way of life in the woods. Stylistically, äijäkirjallisuus is often prose that laughs in a serious way at the ironies of life of the modern male. The ‘hard boiled’, polished laconic style of the leading modernist prosaist of the 1950s, Veijo Meri (born 1928), seems to have influenced many of the male authors of the middle generation, and the economical, vivid sentence is often the distinctive feature of their language. Ironic descriptions of a slightly younger generation of men can be found, for example, in Petri Tamminen’s novel Mitä onni on (‘What happiness is’, Otava, 2008; see Books from Finland 3/2008). The protagonist does not immediately flee the home to fulfil his need for freedom, but rather attempts to live a double life, which he sees as invigorating:

Clandestine romantic relationships caused our fathers’ generation enormous inconvenience: letters dressed up as official correspondence, calls to work on the family phone, evening walks near the beloved’s home, perhaps the wave of a hand from a balcony. It all must have been quite burdensome from the standpoint of guilt. With email and text messages, an affair can be mastered easily. It overlaps with family life. During a lull in the impassioned messaging you can go warm up the macaroni and cheese or empty the washing machine. The whole relationship experience resembles a harmless hobby that is a delight for everyone: dad gets something to do and the family gets an energetic dad. The Finnish man ran out of things to do with the advent of urbanisation. Neither lathes nor circular saws fit in the living room. Now the computer has saved men; the computer is the new lathe. If there is another woman waiting at this lathe, then all is actually better than before.

Authors have repeatedly protested against gendered categories and have experienced the male perspective of äijäkirjallisuus as a demeaning invective. It is actually more of an admission that gender matters: it is everyone’s fate, at least in Finnish culture. Depictions of identity written by men often concisely represent something of the prototypical Finnish distress with which both men and women are just as able to empathise. What is at stake is the different culturally-directed expectations placed on the genders and how they are fulfilled. The overvaluation of work in Finland is a burden felt by both genders. You simply have to be able to manage as both a highly educated professional and a middle-class builder of a family and a lifestyle. This hubris has been developed by Kari Hotakainen in his Finlandia Prize-winning novel Juoksuhaudantie (‘Trench Road’, WSOY, 2002). It is a tragicomic depiction of a man who attempts to acquire the idyll of the single-family home for his family at any cost. The novel Vihan päivä (‘The day of wrath’, WSOY, 2006) by Markku Pääskynen (born 1973) recounts the tragedy of a nuclear family gone bankrupt: in her distress, the mother massacres her family and herself. Economic and mental bankruptcy have led to several family murders in Finland this autumn, and in my opinion literature has long been predicting these tragedies as the final result of meritocracy.

What has been called the twin burden of the individual’s professional and family life has expanded in the post-modern consumer society to become a triple burden: body and appearance have become the final means to influence one’s identity. The market economy of fashion, beauty and style, combined with visual media, have created an even greater externalisation of body image. This can be seen best in literature written by young women; their literature describes the only ostensible freedom of the body as an object of external control. It is especially noteworthy how sexuality has become a required part of the life of an individual that has to be dealt with like any other job. Contemporary Finnish literature is inundated with depictions of hypersexual, frustrated people. This lifeproducing drive and source of energy turns against the individual, as for example in Lääkäriromaani (‘Doctor novel’, Teos, 2008) by Riku Korhonen (born 1972).

One can also take a splendid crack at developing, at least tongue-in-cheek, the concept of muijakirjallisuus (chicklit) alongside äijäkirjallisuus: it is, then, ‘Girls Own’ literature, with feminine overtones and the topoi that form from the pressures that pile up on the modern female. Cultural sayings are revealing. A woman who has successfully balanced career and family in Finland is called a ‘good bloke’. She is thus elevated and comparable to men, a warrior and survivor of the Winter War. The picture of a strong Finnish woman is often connected to the stories of äijäkirjallisuus. A man struggling at the edge of survival is joined by a woman, whose wisdom and skill save the man, if only he allows it. This setup repeats itself bewilderingly often in literature written by men and absolutely deserves further study. The flipside of the caricatured superwoman is the tragic current in women’s literature. The most discussed themes introduced in works by young women over the last ten years include depictions of motherhood, and above all, first-time motherhood. These themes are closely connected to the oppression of body image and the multiple roles ascribed to women that have appeared year after year in debut novels written by young women. The freedom of the modern woman is revealed as illusory at the latest in motherhood, which is not a choice easily renounced once made. Baby blues – postpartum depression – is not only the special difficulty of women who are prone to depression in these literary presentations, but rather it is indicative of a larger crisis of female identity and it ought to be treated as a social issue. The depiction of depression as such is very common in Finnish literature today. When written by younger women it means stories of eating disorders and sexual anxiety; in men’s portrayals, violence and alcohol are emphasised. Even though authors – Kari Hotakainen for example – emphasise that their fiction is not sociological research, the critical reader recognises the correlates of literature in reality with more certainty today than in ages.

An interesting difference from earlier periods – for example the modernism of the 1950s – can be best seen in poetry. The most evocative growth spurts in Finnish poetry in the beginning of the 21st century have come in the collections written by young authors. Themes involving gender can also be found in their work and are dealt with in varying ways. It even makes one want to comfort oneself by believing the old claim that it is poetry that is the forerunner, that it sees the future. Poetry appears to be seeking multisensory release both for women and for men while the prose being written by young women in particular remains weighed down by gender and locked in various ways in the prison of the body. The strongest areas of contemporary poetry written by women are the comparison of historic and modern images of women, as well as the development of various mythical continua. It is no coincidence that the young poets Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen (born 1977), Saila Susiluoto (born 1971) and Johanna Venho (1971) have returned to the wellsprings of Finnish folk poetry in their work, both rhythmically and symbolically. The nods to procreative womanhood woven into the poetry of Susiluoto and Venho almost feel like a new invention. Somehow they manage to write about motherhood as a natural facet of womanhood. The female body and all that goes with it can still be something that supports the ego rather than just breaking, closing off and victimising the ego as previous generations of writers often claimed.

Johanna Venho

(Give way! 1.)

I skied through an arch of trees

into snow-forest, onto the track,

and yelled to you from far back:

‘Now I know! Penelope had given birth!’

The antique heroic journey,

the leap into the unknown,

the way down into Hades,

the miracle and the self-conquest –

Oh Odysseus, you had to rush.

I fall flat on my face in the snow,

a ski stuck in a bush,

and somewhere far away you’re flashing downhill,

far away freighted trucks are trundling along,

I’m weaving my web unhurrying,

day in day out,

and snow’s gently descending and burying me.

I’ve taken a swipe at the surface of the magic pond

with my ski pole, I’ve smashed the one-night’s ice

and the pictured images, colours

I tried to camouflage myself with.

The font’s a fouled-up kaleidoscope

with the bits rattling, and on the bottom

knowledge and truth: they’re a thread of grey and gold

I’ve got to roll into a ball I could throw

or weave into a kite’s long rope.

I’ve fingered the dust by the wall,

and now I’ve slicked my hands on

full-blooded, ripe, sticky clay;

give me a little more time to mould it;

wise old women

often take off in an odd direction,

bonneted with snow-white

they collect pieces of porcelain,

happiness is making other folk feel good.

I lie awake at night and see

down to the end of the track: the snow’s melting

and the children are messing about in the mud

with bare feet, making them bird-legged,

their shoulder blades sharp,

their hair light and silky as a newborn sun.

By day we make binoculars out of toilet rolls –

here you are, you’ll see the truth with them,

but don’t get scared, it’s bald,

and, stripped off, it’s nothing at all,

till you toss it into the works

to spin round, getting crushed in the cogs:

you feed the final product to the hungry.

Don’t laugh. Many stop half way,

basking in an insight,

what would I know about that, I’m a tabula rasa,

the unread texts

vanish from me as if swept by a great sleeve

with a sneezing and a snorting;

when I ladle porridge onto the plates,

I’m ladling golden porridge

(From Yhtä juhlaa [‘It’s all a big celebration’, WSOY, 2006]; translated by Herbert Lomas, published in Books from Finland /2006)

In the poetry coming from young men, the masculine identity in its most formulaic form gets the boot. In his debut collection Vantaa (‘The river Vantaa’, Otava, 2007), Vesa Haapala (born 1971) writes amazingly naturally of a man as a writer-link in a chain of generations of hunting and fishing fathers. In his collection Lohikäärmeen poika (‘The dragon’s son’, Tammi, 2007),Teemu Manninen (born 1977) writes flarf poetry, which draws its material from internet forums and is full of archetypical masculine violence and aggressive language, and yet what surfaces is the eternal question: how should we live? Finnish literature is able to challenge its readers to answer.

Translated by Owen Witesman

(First published in Books from Finland 4/2008.)

No comments for this entry yet