Little and large

5 November 2010 | This 'n' that

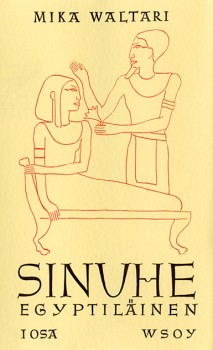

A Finnish tale set in Egypt: Mika Waltari's post-war novel has been translated into 30 languages, English in 1949

a about after again against all also always an and another any are around as at away back be because been before being between both but by came can children come could course day did didn’t do does don’t down each end er even every fact far few find first for from get go going good got great had has have he her here him his home house how i i’m if in into is it its it’s just kind know last left life like little long look looked made make man many may me mean me might more most mr much must my never new no not nothing now of off oh old on once one only or other our out over own part people perhaps place put quite rather really right said same say says see she should so some something sort still such take than that that’s the their them there these they thing things think this those though thought three through time to too two under up us used very want was way we well went were what when where which while who why will with without work world would year years yes you your

Doesn’t this just run like a poem? An extract from somebody’s stream of conscience? ‘…again against all also always… quite rather really right said’? Actually it’s a list of the 200 most used words of the English language in alphabetical order.

This remarkable list is among the references* in a new doctoral thesis from the Department of Modern Languages at the University of Helsinki, Englanniksiko maailmanmaineeseen? Suomalaisen proosakaunokirjallisuuden kääntäminen englanniksi Isossa-Britanniassa vuosina 1945–2003 (‘To world fame in English? The translating of Finnish prose fiction into English in Great Britain between 1945 and 2003’).

Instead of textual analysis, the author, Raila Hekkanen, approaches the subject by placing translation activities into a sociological context – in what sort of circumstances translations were produced, which factors were influential in the process – and employs descriptive translation and language research.

In England between the years 1949 and 2003 only 28 prose works by Finnish authors were published; of these, only the 1950s translations of 12 historical novels by Mika Waltari (1908–1979) gained any notable popularity. However, Waltari’s most famous novel, Sinuhe egyptiläinen (The Egyptian), was not translated from Finnish but via Swedish, and it was heavily edited and cut. More than the translators, it was the publishers who were to blame. This kind of ‘translation’ is no longer practised, as norms of translating and editing have changed greatly over the past couple of decades.

Hekkanen aims at addressing wider theoretical questions concerning the roles of different factors of the translation process and the placement of the translation in both its original and target cultures as well as in the ‘interculture’ between them (people who live in a dominant English-language culture, but with contacts with Finland). The impact and significance of public funding in commissioning and publishing literary translations, as well as recent changes brought about by the expansion of the European Union, have hardly been researched so far. In Finland, the role of FILI (formerly the Finnish Literature Information Centre, now the Finnish Literature Exchange) has become essential in the role of establishing contacts with (and between) translators of various languages and and providing opportunities for training.

Raila Hekkanen also interviews several translators and editors involved with an English-language literature journal featuring samples of Finnish literature – namely Books from Finland; the translation and editing processes of the journal since the early 1980s are also illustrated in this academic work.

And that’s nice: we do indeed been try to delight a big-language culture, i.e. English-language readers (be they native speakers, genuine foreigners or Finns who read English), with interesting stuff from a small-language culture, provided by a) Finnish authors, b) translators who are willing to work more or less for a song. As the Finns know very well, it takes two to tango (we’re collectively addicted to our Northern, melancholy version of the fiery Argentine dance). As long as you’re prepared to go on reading, we’ll go on writing, editing and translating. We get a kick out of what we do, and we hope you do, too.

*) source: Sara Laviosa-Braithwaite: The English Comparable Corpus (ECC): A Resource and a Methodology for the Empirical Study of Translation (University of Manchester, 1996) a about after again against all also always an and another…?

Tags: novel, publishing, short story, translation

1 comment:

12 November 2010 on 2:37 am

Yes, it’s quite absurd that the English translation of Mika Waltari’s novel Sinuhe egyptiläinen has only been published in a heavily cut and edited version and not translated direct from Finnish. Isn’t it about time we had a brand-new translation of the full work? Väinö Linna’s Tuntematon sotilas is another work whose English translation has been frequently criticised.

Two classic Finnish novels – neither of them exactly recent – still awaiting proper translations a long time after first publication!!!