Online, offline?

17 April 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

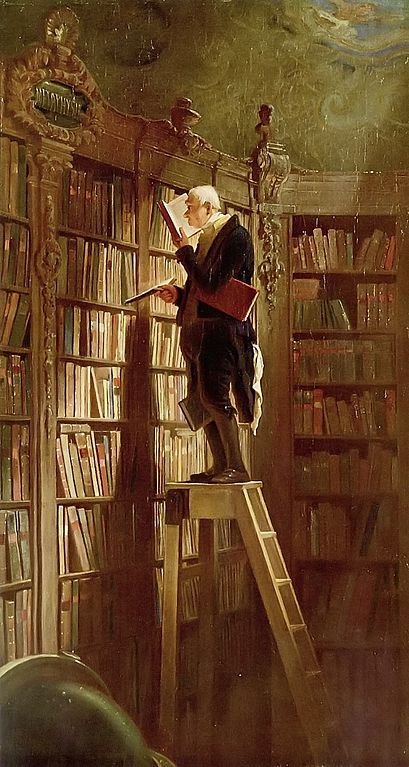

‘The bookworm’ (old-fashioned) by Carl Spitzweg, ca. 1850. Museum Georg Schäfer. Photo: Wikimedia

Ebooks are not books, says Teemu Manninen, and publishers who do not know what marketing them is about, may eventually find they are not publishers any more

At least once a year, there is an article in a major Finnish newspaper that asks: ‘So, what about the ebook?’ The answer is, as always: ‘Nothing much.’

It’s true. The revolution still hasn’t arrived, the future still isn’t here, the publishers still aren’t making money. In Finland, the ebook doesn’t seem to thrive. The sales have stagnated, and large bookstores like the Academic Bookstore are closing their ebook services due to a lack of customers.

Why is Finland such a backwater? Why don’t Finns buy ebooks?

The usual explanation is that Finland is a small country with a weird language, so the large ebook platforms like Amazon’s Kindle and Apple’s iBook store have not taken off here. Another patsy we can all easily blame is the government, which has placed a high 24% sales tax on the ebook. If that isn’t enough, we can always point a finger at the lack of devices and applications or whatever technical difficulty we can think of.

But the main problem is not that Finns don’t want to buy ebooks; I think it has to do with the quality of the Finnish engineering mindset.

This mindset, with a herd-mentality often approaching hysteria, only looks at technical details, trying to solve issues that are of no concern to actual users. But the real problem is that we don’t seem to understand that the ebook is not a new way of distributing immaterial copies of formerly material products.

Every time new media are introduced, they are always compared with old media. This is a mistake. The television is not a radio with pictures or a cinema in the living-room, the newspaper is not a clay tablet, the internet is not the iPad, and the ebook is not, in fact, a book at all, and the publishers of the future are not the publishers of the past.

If the ebook is not a book, what is it? In a word, an archive – or at least a graphical representation of one. When you buy an ebook, you buy access to a part of this archive, and if you think of it this way, you may start to understand what’s going wrong with Finnish ebook sales.

Here’s the thing: if people aren’t buying your goods, that means there is something wrong with them. In the case of ebooks, it means your archive is flawed and your service is awful. Think of it this way: it probably wouldn’t be a good idea to build a library underground, then not tell people how to find it, to make access difficult, the rooms cramped and dark and not fun at all to hang around in, to stock the few shelves with only a couple of the latest bestsellers which you can only read while standing up, so that in the end you will just want to get the hell out of there, never wanting to even think about literature ever again.

So, if the ebook is like an online library, then surely the way to make people want ebooks is to make that library a place they want to visit? This is, in fact, and regardless of whether or not you accept my thought-experiment, why Amazon and Apple are successful: because they have understood that ebooks are not books, but a new form of digital media they can provide you with, along with music, books, movies and whatever else you fancy consuming on your devices, and the moment you realise this, you are hooked in to being their customer, simply by the desire to live in the world they have furnished for you.

This is why, for example, looking at comparative sales figures, i.e., what percentage of publishers’ sales are ebooks or print, completely misses the point of what is going on with textual media and what the future of reading will be like.

If the ebook is not a book, it follows that publishing ebooks is not the same as publishing books. Therefore publishers either need to transform themselves radically if they are going to survive, or they will be forced to assume a very different role in the marketplace of the future, either as providers of niche artifacts (all literary presses will be small presses in the future) or subcontractors in larger projects such as media tie-ins (‘look, it’s a book, a lecture tour, a movie and an online comic!’).

It’s hard to adjust to this new online world. I’ve worked as a small publisher myself with a group of other people for three years now, and if there’s something I’ve learned, it’s that publishing is a tough business: unpredictable, stressful, almost impossible to streamline: no one really knows what sells and why.

Because of this volatile nature of the business, publishers tend to be conservative folk. That’s why they are also deathly afraid of change, afraid of either pirates or of being forced to give out their content for free, and therefore almost convulsively incapable of negotiating new copyright agreements or distribution plans.

But the internet is not the enemy. As a lesson in courage, publishers should look to their sisters in print media, the magazines and newspapers. It took them years to understand that they would have to start migrating to the internet, to develop a new economic model to sustain themselves.

Surprisingly, it isn’t that hard if you have the guts to take the leap. When the New York Times announced it would begin charging readers for its online articles, every media critic balked: surely this would be the death knell of a venerable institution. On the contrary. The NYT is now making a profit, thanks to online subscriptions.

So go ahead, publishers, take the leap. I urge you. Just remember: the ebook is not a book, and we are most certainly not in Kansas anymore.

Tags: book trade, ebooks, internet, publishing

No comments for this entry yet