The many arms of Krishna

14 August 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

A feast by the Ganges. Photo from Pirjo Honkasalo’s film Atman

Cinematographer, camerawoman and director Pirjo Honkasalo has travelled and filmed widely – Japan, Estonia, India, Chechnya, Ingushetia, Russia – and her documentary films in particular have gained fame. American film critic John Anderson interviews Honkasalo; they talk about her documentary film Atman (1996) about a pilgrimage in India.

Edited extracts from Armoton kauneus. Pirjo Honkasalon elokuvataide (‘Merciless beauty. The film art of Pirjo Honkasalo’, Siltala, 2014; translated from English into Finnish by Leena Tamminen)

You can almost catch a whiff of the Ganges watching Atman [Hindu term, ‘self’], a documentary film in which religious pilgrimage, devotion, exhilaration and hysteria compete with tormented bodies, physical mortification, corpses, pollution and the acrid smoke of ritual cremation for domination of the viewer’s senses. The fact that it won the top prize at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam in 1996 proves there is, if not justice, then good taste in the world. With all due respect to her previous work, Atman signified the full manifestation of Honkasalo’s genius.

What is it about? Eternity. Also, Jamana Lal: a member of the low-caste of Baila, a wifeless, crippled devotee of Lord Shiva whose mother has died, and who must – according to Hindu tradition – take her ashes from the ostensible mouth of the Ganges to the foothills of the Himalayas.

His brother accompanies him, for part of the journey; Jamana Lal meets a woman, Shanta, with whom he falls in love. By way of Varanasi, the holiest city in India, they reach Haridwar, where the brothers make a flower sacrifice to their late mother. After an argument, the married brother leaves, and Jamana Lal and Shanta proceed deeper into the Himalayas. Ultimately, the couple travels back to Jamana Lal’s native village of Moshi, where he distributes among his fellow villagers the holy water he has taken from the Ganges.

Jamana Lal’s epic endeavour – don’t forget that he is unable to walk – might have been enshrined in the Bhagavad Gita, or memorialised on a several-metre-long, gold-threaded tapestry. Instead, it is immortalised on film, the making of which involved corruption of every kind, unspeakable beauty, and death.

In following Jamana Lal’s 6000-mile journey, visiting a million-strong religious festival along the way and portraying the India she meets in a manner that is both intimate and awe-struck, Honkasalo creates a non-fiction film that has virtually no stylistic distinction from a narrative feature film. [ – – ]

‘Whether you’re making fiction or documentary, you’re the same human being, and while the method may be different, the main thing you’re trying to say is not so different. The working methods are different, but I’ve always said is that there’s one thing that really separates the two styles and that’s the ethical dimension. In documentary there’s always this ethical question, because you are using real people to express yourself. In fiction, you pay the actors, so if they get a divorce after the film it’s none of your business,’ Honkasalo says. [ – – ]

‘In documentary filmmaking I think that if you make films about public figures like George W. Bush the ethical question is very minor: they have put themselves in a position where they know what the media is, and how it works. But if you portray ordinary people, if they say yes to the film it doesn’t mean they take the responsibility off you, because the film might influence their life in a way that they cannot possibly see in advance. And you might very easily affect their social position in their own community, such as in Atman. Which is an extreme.’

The German broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk and the German film distributor Telepool had invited Honkasalo to make the film, part of a project involving different filmmakers profiling different parts of the world. ‘The only conditions,’ she says, ‘were that it had to take place in India, and it had to be 35mm. So I went to India with Pirkko [Saisio, Honkasalo’s spouse] and we spent a month there. I didn’t want an Indian with me because I thought the Indian would not only be translating the language, but also the culture. I had been to the country several times, but I wanted to look at the culture through my own eyes. Of course, I realised, for shooting, I needed Indians.’

During the month she and Saisio were there, Honkasalo searched for a subject, to embody the theme she’d arrived at. ‘I’d already decided I wanted to do someone on a pilgrimage, which I think is such an interesting concept. Why, throughout the history of mankind, have people always thought that if you undertake a very tough journey, far away from your home, you will return on a higher spiritual plane? When the Russian Revolution took place, there were eight million pilgrims on the road. It’s not only an Indian thing. But the thought is fantastic – you have to go on a very strange journey outside of your own social milieu, and then you come back as another human being.’

She watched thousands and thousands of pilgrims passing by. In the foothills of the Himalayas, up in the north, there was very heavy rain. There was also a small tent where people were serving tea.

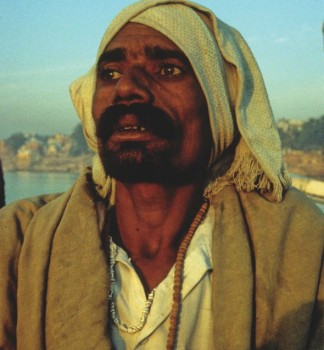

Pilgrim: Jamana Lal in Varanasi. Photo: Atman by Pirjo Honkasalo

‘So I thought I would go in and wait out the rain,’ Honkasalo says. ‘As I did, there was a family coming into the tent and it was suddenly totally packed. But I looked in the eyes of Jamana Lal, I took a picture, and I said, “That’s him.” I didn’t even notice how crippled he was. But his eyes – I knew, “That’s him!”’

With no one there to translate, Honkasalo managed, with a notebook and some hand gestures, to make him understand that if he put his address in her notebook, she would send him the photographs she’d taken.

‘Then I went home, I wrote a script of 30 pages, sent it to the German producers, and they said, “Fantastic, here’s the money.”

‘Everything was, of course, invented. Then I went back to India with my assistant Marita Hällfors, contacted some Indian filmmakers and said, “Can you take us to this man?” No, they said, they actually couldn’t.

‘They said, “Well, he can’t really write – you can tell which state he lives in, but not where exactly.” I thought, “Uh-oh, now I’m in trouble: I’ve written the script for the Germans and got the money but we’ll never find him.”’

But she had the photographs. ‘So we hired a car and went from village to village with the photos and eventually someone said, “Oh yes, Moshi village.” I think we’d been there two, three weeks. But there he was.

‘And what was fantastic – although bad luck for him – was that his mother had just died.’

The sons, according to Hindu tradition, had to make a pilgrimage. ‘If they don’t make a pilgrimage, the mother can never join the realm of the souls of the ancestors. Her soul was going to be restless. So there I was with a real pilgrimage. You could make one up, of course, and it would not have been improper to make that sort of a pilgrimage. But with the mother dead, they had to go on one for real.’

But the relationship with Jamana’s brother had been fractious from the start. The film ‘company,’ as it were, had agreed to meet in Calcutta and begin from Sagar Island. ‘It’s where the Indians think the Ganges ends – it actually flows into the sea in Bangladesh – but for Indians the mouth is at Sagar Island, which is south of Calcutta. When we got to Calcutta the brother was not there. I heard that his employer told him we were going to steal his kidneys.

‘They had brought some other people from the village to replace the brother, but I said, “No, I want this to be a true story.”’

Luckily, she had Farzaan. ‘Farzaan was a Parsee from Bombay,’ she says. ‘But he could understand us and the Hindus. A wonderful young man.’

Honkasalo would not begin filming until the brother was on the scene. ‘And we hadn’t booked anything, because we didn’t know our schedule. So we took trains, donkeys… it’s so damn cold on the trains.’

They went to the marble quarry where Jamana’s brother worked. ‘Farzaan said to me, “This is limestone, this is not marble.” We found the brother and said, “Can we talk to the owner of this quarry”? The son of the owner, in his white suit, was really smug and said, “I think filmmakers cheat people. They are cheaters.”’

‘Farzaan looked at him and said, “Yes, it’s true, there are filmmakers who cheat people. And there are quarry owners who sell marble that is actually limestone. But we are not cheaters, are we?” The owner started to laugh, and said, “OK, let him go.”’

So Honkasalo took the brothers and Jamana’s brother’s family back by train and donkey and went to Sagar Island. [ – – ]

On the road: equipment in Calcutta. Photo: Atman by Pirjo Honkasalo

Because they were shooting Atman on 35mm equipment, Honkasalo tried to take as little as she could on the trip, ‘…but anyway it was 600 kilos, and 48 cases, because 35mm adds to everything – everything is bigger, the film cans are bigger, and everywhere we went in India we went via public transport. We didn’t hire a car for ourselves; we were on buses and trains, and I remember once we were coming with these 48 cases to a train station, and we were quite late and I realised that Jamana Lal couldn’t make his way through the crowd fast enough to make the train. We asked one of those guys who carry your suitcases, “Could you carry him into the train?” Absolutely not. Jamana Lal was so low-caste that even a porter wouldn’t touch him, not even for money. But then our wonderful Estonian soundman, a natural-born Gandhi, put Jamana on his back and ran for the train.’

‘I never pay people in documentary films,’ Honkasalo says, ruminating. ‘I know more and more documentary directors pay, but I think it changes the relationship between the director and the protagonist in the film. I’m stubborn in that they have to put themselves in the film because they want to do it, and not in the hope of getting money.’

At the same time – and Honkasalo is not alone in this – there is a feeling among documentary filmmakers that they have taken something from their subjects, and that it should be repaid, in some way.

‘I’ve decided that if I get money from prizes or festivals, then it’s 50-50,’ she says. ‘If we, the people who are making the film, succeed, then part of it is theirs. Atman won the Joris Ivens prize in Amsterdam, so I got money – by Indian standards, a lot of money. So, should I give half of it to him? Or do I give him a small amount of it every year? Then I thought, “This is such a Western mindset, that we have to mollycoddle the rest of the world.” He’s a grown-up man. Either I give it to him, or I don’t give it to him. But I can’t take responsibility for him.’

She had a friend who was going to India, so she put the money in an envelope and sent it to Jamana Lal.

‘In Moshu village,’ she recalls, ‘he was the lowest of the low. He lived in a hut, not even a house, and he was crippled as well as of the lowest caste; our Indian location manager wouldn’t even enter his house or drink the tea he was offering. He built a house with the money, which totally changed his social position in the village. And then he was murdered. [ – – ]

‘Of course, I cannot say I murdered him,’ Honkasalo says. ‘But I can’t get it out of my mind. It’s obvious that someone was so jealous of his new position that he murdered him. Did I destroy his life, especially as I knew how low his status in the village was? But I think that for him, being in the film, falling in love with Shanta, was probably the best time of his life, maybe the only time everybody really treated him well.’

A year later Honkasalo and her assistant Marita Hällfors – with whom she has been working for 20 years – got a letter from India.

’It was written by a young man who said he’d had a dream about Jamana Lal. The same thought occurred to Marita and me almost immediately: This is the murderer, who started having dreams and had to do something. He said he would like to discuss Jamana Lal and his life with us, but we both felt that he was the murderer, returning to the scene of the crime in a way.

‘We never answered him.’

Atman (1996) was the third part of Honkasalo’s Trilogy of the Sacred and the Satanic. Mysterion (1991) and Tanjuska and the Seven Devils (1993) were, in their own way, about religious devotion. ‘It is what interested me very much; what I tried to achieve but don’t know if I succeeded, was handling the idea that somehow we have lost our innocence,’ Honkasalo says. ‘Our whole life is so fragmented. We have work and family and religion perhaps, or passionate irreligiousness. But in Jamana Lal’s life everything was united. Even though he made a pilgrimage, his religion lay in the fields, in animals, in everywhere. It’s one compact world and consciousness, and death too is a step on the path of life.

‘What I was trying to do, if only for a second, was to regain my innocence and experience everything as a whole,’ she says. ‘Of course, their religion also brings them anxiety, as does ours, but for them a source of happiness is to see the wholeness of life. And it’s not something they have analysed.’

‘Sometimes I think I got into it for a moment,’ she says. ‘But our minds are destroyed, and so fragmented, we can’t reach the level of consciousness that brings them joy. And they’ve always been tolerant in Hinduism – there are so many gods and you can pray to each one. The gods are all attributes of one consciousness. I think maybe that is why we have been driven out of paradise, we can no longer sense the world as a whole.’

The film grew meets the guru: from right, the guru, Jamana Lal, Pirjo Honkasalo

Jamana Lal was not learned in the conventional sense. ‘What he understood, he had learnt by visiting his guru,’ Honkasalo says. Sometime after the filming she got a letter from Jamana: ‘It read, “I’m so sad; my guru has died. Please, do me a small favor and come here immediately…” Maps meant nothing to him. For him, “near” and “far” meant different things than to me. Still, I felt we connected. In some sort of silence.’ [ – – ]

‘A documentary film really requires a great deal of humility. People are not idiots. They read you – not only do you read them, they read you. And you never get anything that you don’t deserve. When I was filming Tanjuska in Father Vasilyi’s church, an old woman tapped on the side of my camera. I took my eye away from the viewfinder. She looked at me kindly and said: “I just want you to know that if you have any secret intentions, you will go to hell.” That’s the best piece of advice to a documentary filmmaker I’ve ever got.

‘So, when I get tired of being humble, I’ll evidently return to fiction.’

No comments for this entry yet

Trackbacks/Pingbacks:

9 January 2015 on 8:31 pm

[…] Merciless beauty. The film art of Pirjo Honkasalo (2014, Siltala). Read excerpts from the book here. The Critic’s Choice is meant to assist in distributing Finnish documentary film abroad by […]