Author: Nina Paavolainen

Hannu Raittila: Terminaali [Terminal]

23 January 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Terminaali

Terminaali

[Terminal]

Helsinki: Siltala, 2013, 454 pp.

ISBN978-952-234-174-7

€32.90, hardback

The airport is a fertile environment for a contemporary novel: a crucible of chance encounters. In his sixth, extensive novel, Hannu Raittila (born 1956) masterfully combines plot and structure: there is adventure, personal relationships, hard living, a love affair, life on a remote Swedish-speaking island. Commodore Lampen sets out to look for his daughter Paula, who has been forcibly brought back to Finland after spending years touring foreign airports. Back in the 1990s Paula and her friend Sara spent a lot of time at Helsinki airport, which developed its own culture of international encounters; this then took them abroad – by accident, on 11 September 2001. Various adventures ensued, including an involvement with the Syrian civil war. Globalisation is based on the free mobility of goods and people, but it also means crumbling of societal structures, and in Raittila’s novel – paradoxically enough – the growing rarity of human encounter.

Tuomas Kyrö: Kunkku [The king]

19 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kunkku

Kunkku

[The king]

Helsinki: Siltala 2013. 549 pp.

ISBN 975-952-234-173-0

€29.90, hardback

This novel is a satirical alternative history of successful Finland and self-destructive Sweden. It is also the story of the king of Finland – the protagonist, Kalle XIV Penttinen, is driven by his instincts, which causes him to fail as a family man. Pena, as he is called, would like to play tennis all day long and watch pole dancing at night. Finland is a fantastic wonderland of film and music industry, tennis, space technology and innovative legal usage, whereas Sweden, ravaged by war, suffers from the trauma that passes from one generation to the next. Estonia has done well for a long time, and the Soviet Union (sic) is a stronghold of democracy. Chuckling, Kyrö turns history upside down. As a writer of short prose and tragicomic novels he is currently a very popular author. However, this time his typically witty associations and inventive comedy suffer from the sheer size of this novel.

Leena Parkkinen: Galtbystä länteen [West from Galtby]

19 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Galtbystä länteen

Galtbystä länteen

[West from Galtby]

Helsinki: Teos, 2013. 339 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-510-7

€32.90, hardback

Leena Parkkinen’s first novel, Sinun jälkeesi, Max (‘After you, Max’) was awarded the Helsingin Sanomat literature prize for best first work of 2009. Her new novel contains crime story ingredients, but the focus is on love between siblings, loss and the demand for truth. The story begins in 1947, after the war, on an island in the south-western Finnish archipelago. Sebastian, brother of Karen, has returned from the front; it’s time to mend the best clothes and dancing shoes. But to the horror of the island community, the body of a young girl is found on the shore, and Sebastian gets the blame. Sixty-five years later her brother’s fate has not left Karen alone, and she sets out to find the truth. Capable of handling different times, Parkkinen (born 1979) is also a skilful interpreter of conflicting sentiments, as unexpected twists develop towards the end.

Pauliina Rauhala: Taivaslaulu [Heaven song]

12 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Taivaslaulu

Taivaslaulu

[Heaven song]

Helsinki: Gummerus, 2013. 281 pp.

ISBN 978-951-20-9128-7

€29.90, harcback

A religious revivalist movement is the framework for this skilfully written first novel. A young couple, Vilja and Aleksi, dream of a brood of children. Nine years and four children later Vilja feels that all joy and strength has drained away from her life. Living the reality of their religion’s ban on family planning, the couple is hit hard by the fact that Vilja is expecting twins. This is too much for her; she feels crushed by anxiety and fatigue. The ethical ground of parenthood, the good and bad sides of a religious community as well as the myths and expectations surrounding motherhood are Rauhala’s main themes. This impressive tale also contains a love story; Aleksi is a credible and sympathetic husband who first and foremost wants to believe in his wife and his family.

JP Koskinen: Ystäväni Rasputin [My friend Rasputin]

5 December 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Ystäväni Rasputin

Ystäväni Rasputin

[My friend Rasputin]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2013. 355 pp.

ISBN 978-951-0-39772-5

€29.50, hardback

Prophet, healer, mystic – and political player and lecher. The hectic life of the Russian Rasputin, which ended in 1916 in assassination, offers excellent material for JP Koskinen’s novel. The fictive narrator is the young Vasili, who Rasputin hopes will be a follower. The mix of fear and adulation and wild events, described from the point of view of the young boy, are persuasive. At the court of Tsar Nicholas II Rasputin gained favour because the Tsarina trusted almost blindly in his healing abilities: the imperial family’s son Alexei was a haemophiliac. JP Koskinen’s earlier works include science fiction. Ystäväni Rasputin is a skilful writer’s description of historial events on the eve of the Russian revolution; it paints an interesting and intense portait of the atmosphere and events of the St Petersburg court. Koskinen does not over-explain; interpretation is left to the reader. The novel was on the Finlandia Prize shortlist.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Asko Sahlberg: Herodes [Herod]

28 November 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Herodes

Herodes

[Herod]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2013. 680 pp.

ISBN 978-951-0-39546-2

€40, hardback

Sahlberg’s short, concise novels about Finland’s recent past are here followed by a massive volume set in the early days of Christianity, in Judea and Galilee. Sahlberg’s accurate use of language, his pithy dialogue and vivid sense of history guarantee a reading experience. John the Baptist is the novel’s great prophet; the short, bow-legged Jeshua remains in his shadow. The main character, however, is Herod Antipas, the Roman tetrarch, and Herod’s wife and his servant are also central. Representing the imperial power in the Judea area is the prefect Pontius Pilate. Herod is a sympathetic character who has, throughout his life, alternately enjoyed and suffered from the use of power. How does power change a man? What is the meaning of trust and loyalty – not to mention love – when life is full of fear, doubt and extortion, poisoners and agitators? Sahlberg (born 1964) also opens up perspectives on the examination of our own time. The novel was on the Finlandia Prize shortlist.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Kjell Westö: Hägring 38 [Mirage 38]

31 October 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Hägring 38

Hägring 38

[Mirage 38]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2013. 296 pp.

ISBN 97895152332069

€34, hardback

Kangastus

Suom. [Translated into Finnish by] Liisa Ryömä

Helsinki: Otava, 2013. 334 pp.

ISBN 9789511274032

€29.90, hardback

The previous novels by Kjell Westö (born 1961) have been sweeping in their scope, encompassing several generations. Westö’s writing is characterised by a precise instinct for historical details and love for his hometown of Helsinki. Hägring 38 focuses on the year 1938; the new ideas of that era and the worsening political climate in Europe are reflected in the differences of opinion among a group of Finland-Swedish gentlemen. In June of 1938 these friends attend the opening gala for the new Olympic stadium in Helsinki and watch as the winner of the 100-metre dash, a Jew, is demoted to fourth place. [In October 2013, after the publication of Westö’s novel, the Finnish Athletics Federation finally corrected that erroneous decision, which had been made for racist reasons.] Claes Thune, a lawyer who has lost his wife to another man and suffers from depressive episodes, is a leading member of the circle of friends. His new secretary, the taciturn Mrs Wiik, is one of the central figures Westö utilises to portray the prison camps and traumatic events of the Finnish civil war of 1918.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Kari Hotakainen: Luonnon laki [Law of nature]

26 September 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Luonnon laki

Luonnon laki

[Law of nature]

Helsinki: Siltala, 2013. 283p.

ISBN 978-952-2341853

€23.90, hardback

Kari Hotakainen’s twelfth novel is characterised by a dramatic plot. A year and a half ago, the author had a car crash, which he miraculously survived. Luonnon laki draws on Hotakainen’s experience, at the same time continuing the series started by his last two novels, with their commentaries on the contemporary world. The main character, the entrepreneur Rauhala, wakes up in hospital after a car crash and begins the slow process of recovery and rehabilitation. Incapable of movement and dependent on the care of others, the man has time to think – to think, for example of the free healthcare service of a welfare state such as Finland, whose cost, in his case, is high. Ideologically estranged from her father, his daughter is about to give birth to her first child; Rauhala himself is essentially reborn and makes peace with his daughter. Both melancholy and amusing, linguistically rich and delicious in its associatons, this tale and its characters are highly enjoyable.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Philip Teir: Vinterkrig. En äktenskapsroman [The winter war. A marriage novel]

19 September 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Vinterkrig. En äktenskapsroman

Vinterkrig. En äktenskapsroman

[Winter war. A marriage novel]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2013. 326 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-3207-6

€26.70, hardback

Finnish translation:

Talvisota. Avioliittoromaani

Suom. (Translated by): Jaana Nikula

Helsinki: Otava, 2013. 347 p.

ISBN 978-9511269854

€30.30, hardback

This first novel by Philip Teir (born 1980) brings to mind a stereotype of the Finland-Swedish minority: pleasant, controlled, civilised and rather amusing. Teir has previously written short stories, and no doubt his work as a cultural journalist has sharpened his detailed perceptions of society and life in general. Hence, the result is controlled and rather amusing. In the focus are sociologist Max and personnel manager Katarina, who have in their long marriage become alienated from each other. Two grown-up daughters have problems of their own, as a working mother of small children, and as an arts student trying to find a direction for her life. Teir’s characters look for ways to solve their problems: Max seeks the company of a younger woman, whereas the more straightforward Katarina applies for a divorce. Yet, amidst confusion, Teir seems to place his trust in a traditional safety net, represented in the novel by the family and the community. The portrait of a middle-class, academic family with rather ordinary problems is ironically gentle: a pleasant reading experience.

Riikka Pelo: Jokapäiväinen elämämme [Our everyday life]

13 June 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Jokapäiväinen elämämme

Jokapäiväinen elämämme

[Our everyday life]

Helsinki: Teos, 2013. 526 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-389-9

35.90€, hardback

At the centre of Riikka Pelo’s second novel are the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva (1892–1941) and her daughter Ariadna Efron (1912–1975). This broad historical novel depicts the mental landscape of Russia during the period between the two great wars, from the 1920s to the 1940s. The mother is a religious believer and idealist, her daughter a more pragmatic empiricist. The family’s fate is controlled by the Soviet state apparatus, which sends it into exile in Paris where Tsvetaeva’s husband Sergei Efron takes a job as a secret police informer in an organisation devoted to the repatriation of Soviet emigrés. In the 1930s they return to Moscow, where life under the watchful eye of Stalin is filled with difficulty and paranoia. Pelo portrays the awkward relationship between mother and daughter with particular vividness. The indisputable star of the family is the mother – her ambition extends to her daughter, who to her disappointment is more interested in the visual arts than in poetry. The historical characters of Pelo’s impressive novel live their contradictory lives in decades of social upheaval.

Translated by David McDuff

Marjo Niemi: Ihmissyöjän ystävyys [The cannibal’s friendship]

8 May 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Ihmissyöjän ystävyys

Ihmissyöjän ystävyys

[The cannibal’s friendship]

Helsinki: Teos, 2012. 402 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-359-2

€27.80, hardback

Marjo Niemi’s third novel may be described with the adjective ‘intemperate’. The book’s narrator is a thirty-something woman who is inclined to ranting. A friend’s suicide drives her to depression, which breaks out in endless criticism of her friends’ lifestyles. Her tolerance is tested not only by her hedonistic friends but also by an entire continent: she wallows in endless diatribes about the history of Europe and its injustices. The bubbling text forms a meta-level, a book within a book. Only writing seems meaningful: ‘I am really not going to write about my life, because life is a ridiculous joke compared to literature.’ The Great Novel that is being built by the narrator gradually opens out into a story about a mental hospital psychiatrist and one of his patients who has suffered a loss of memory. The author sees her work as a ‘poetic allegory of Europe ‘, but it is also a study of friendship, guilt, envy, and the difficulty of doing good. Caricature of an almost grotesque kind is skilfully combined with straight talking in this clever contemporary novel. Niemi (born 1978) is a dramaturge by training.

Translated by David McDuff

Aki Ollikainen: Nälkävuosi [The year of hunger]

23 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Nälkävuosi

Nälkävuosi

Helsinki: Siltala, 2012. 139 p.

ISBN 978-952-234-089-4

€32.90, hardback

Finland, winter 1867, famine. The historical framework of this first novel by Aki Ollikainen (born 1973) is barren and the twists of the plot, almost without exception, are dark. The novella weaves together two stories: the poor people of the countryside live hand to mouth, whereas city businessmen, the brothers Teo and Lars Renqvist, agonise about their love problems in their well-heated houses. Of a family of four that sets out from the countryside on a begging mission, only one lives to see the following spring and the melting of the snow. The beast in people leaps forth: when there is no longer anything left to lose, humanity, an unnecessary burden, is trampled into the mud. The whiteness of the endless winter becomes the colour of hunger and of death. Ollikainen’s brief and tragically beautiful novel – which won the Helsingin Sanomat Prize for first works in November – tells its cruel tale with a warmth that is not in conflict with the events it describes. When the roads of city gents and country people entwine, humanity wins, light dawns.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Johanna Sinisalo: Enkelten verta [Angels’ blood]

2 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Enkelten verta

Enkelten verta

[Angels’ blood]

Helsinki: Teos, 2011. 274 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-414-8

€ 32, hardback

The literary career of Johanna Sinisalo (born 1958) has embraced fiction, drama, sci-fi and children’s books. Her 2000 Finlandia Fiction Prize-winning fantasy novel Ennen päivänlaskua ei voi and the novel Linnunaivot (2008) have been published in English as Not before Sundown and Birdbrain respectively. In this new novel, set in the near future, the central role is played by bees: widespread beehive failures in the United States and the resulting drop in pollination have resulted in an enormous food shortage that threatens the world economy. Orvo is a loner, the father of Eero, his grown-up son. Sinisalo cleverly works in animal rights activist Eero’s controversial blog comments on animal rights and modern man’s flawed relation to nature. However, this is also the novel’s biggest problem, as the blogging starts to weaken the story, of three generations of men in a family. Both the mythic, parallel reality of the bees and the tough-and-tender relationship between father and son are strong indications of Sinisalo’s narrative skill.

Translated by David McDuff

Asko Sahlberg: Häväistyt [Disgraced]

2 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Häväistyt

Häväistyt

[Disgraced]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2011. 331 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-38275-2

€ 33, hardback

The tenth novel by Asko Sahlberg (born 1964) is reminiscent of the earlier works of this distinctive author: its principal characters are hardened by experience and lead their lives somewhere in the Finnish countryside during a recent period of the country’s history. The sentences are beautifully constructed, and the pace of the narrative is very slow – sometimes even too slow. The main role is played by a middle-aged man who is running away with a woman and a small boy. What they are running away from for a long time remains a puzzle, as does the question of who they are looking for, a man called The Master. In the flashbacks of the last part of the book all is explained, and the rhythm of the story quickens. Considering the book’s desolate, even fatalistic view of the world, it is slightly surprising that everything eventually turns out as happily as in a fairytale. But perhaps this is Sahlberg’s tribute to his characters, and to all of us human beings, for whom he seems to care a great deal? His novel He (2010) will be published in February in England under the title The Brothers (Peirene Press).

Translated by David McDuff

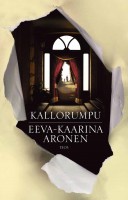

Eeva-Kaarina Aronen: Kallorumpu [Skull drum]

23 December 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kallorumpu

Kallorumpu

[Skull drum]

Helsinki: Teos, 2011. 390 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-413-1

€ 27.40, hardback

Eeva-Kaarina Aronen (born 1948) did not begin her writing career untill 2005, after a long career as editor of the newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. Her third novel Kallorumpu was shortlisted for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011. Aronen’s interest in historical characters and themes that challenge historical truth was already evident in the of her first novel Maria Renforsin totuus (‘The truth of Maria Renfors’, Teos, 2005). At the centre of Kallorumpu is the legendary figure of Finland’s Field Marshal C.G. Mannerheim (1867–1951). The book concentrates on the description of one day in November 1935 by an old filmmaker, the narrator of the novel, who is showing his documentary to a small group of viewers in the present day. He comments on his own film, complementing it with stories about Mannerheim’s home in Helsinki. At home the Marshal’s staff – a cook, a maid and a valet – not only provide narrative twists and turns, but also an insight into the class divisions of the Finnish civil war. Aronen’s portrayal of her gallery of characters is an interesting one, and the novel’s demanding structure, with its alternating time zones, is sound.

Translated by David McDuff