A personal appreciation

Issue 4/1982 | Archives online, Authors

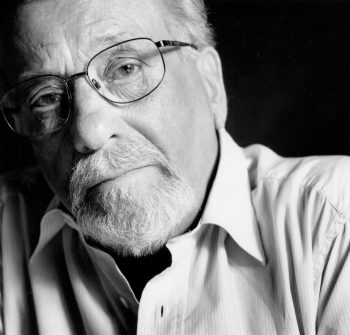

Christer Kihlman. Photo: Magnus Weckström

Almost twenty years ago, a book arrived on my table from a London publisher, a large book called Den blå modern, by someone called Christer Kihlman, of whom I had never heard. Although the book came from Stockholm, in fact it turned out to be the work of a Finland-Swedish writer, perhaps the second or third I had ever read.

The book was to me remarkable. I had never read anything quite like it before, and I have been reading adult fiction for over fifty years. Looking back now in my ancient tatty files, I see I typed three single-spaced pages of synopsis and two and a half of comment, and even translated several extracts, not something I can normally afford to do. This was partly because I was impressed with the book, partly because it was almost impossible to explain the style, or styles, in which it was written, and also it was very difficult to say succinctly just what kind of book it was. The blurb called it a ‘family chronicle’, which in a way it was, but in all other respects it was nothing like what we normally call a family chronicle, anyhow of the kind so familiar from the United States. Two sons trying to live up to their father’s image of a third son, who is dead; but in fact it seemed to me to be the story of one man’s struggle with himself and the agony of existing in a world in which pain and hatred and suffering and despair are constantly victorious over love. In the book was almost everything any thinking person struggles with in his or her mind during a whole lifetime, a search for some kind of meaning in a life that appears meaningless.

The book was a veritable flood of words, of feelings, of the conflict between the demands society makes on a man and the demands that same society makes on a writer. The two brothers seemed to me to be the one man and the conflicts to be those within one unusually sensitive person. To the English reader, the Scandinavian tendency to wallow somewhat in the miseries of our society, and thus be prone to self-loathing, despair and guilts, was prominent. But here was a serious writer, a man with a fairly extraordinary power in his use of words, a man who, even if he could not portray women (there are very few men who can in any language), could write about the nature of man in its complexity extraordinarily well. The only comparable writer I could think of was James Baldwin, a writer I admired enormously at the time, whose books were about love and hate and being black. This Finland-Swedish writer’s book seemed to be about love and hate and the point of living at all. I said so, knowing at the same time that the book was so different from anything else in this publisher’s list (apart from Baldwin), that there was probably little hope for it, quite apart from the complications and expense of having it translated. That was that.

I never heard or read another word about this writer until I was invited, a great many books and translations later, to a translators’ seminar in Finland in 1981. Before going, I met a Finnish friend who was by chance in London at the same time as I was. My knowledge of Finland-Swedish literature was skimpy, to put it mildly, and entirely random, confined to books arriving on my table for reporting on. In the course of our conversation over coffee, I mentioned Christer Kihlman, who had stuck in my mind, and asked whether he were still alive, a remark which caused some amusement. (He is at least ten years younger than I am.) I am slightly better informed these days. I have read more of Christer Kihlman’s books and translated Dyre prins, another major work with so much in it that if I were to write a report on it, the report would be as verbose and complex as the one written twenty years ago on Den blå modern.

Dyre prins, Sweet Prince, was a pleasure to translate, not easy, but so forceful that some of the strength of the writing was somehow transmitted to me. The book is the story of one man; a powerful ruthless character this time, who starts from humble circumstances and is enormously successful in life, both in business and with women, and then, when he comes to try to write down his life, to recall it, to write his own autobiography, he finds he cannot, the memories will not come out on paper as he thinks he sees them, and finally he begins to see glimmers of truth about himself. It breaks him.

The extract printed here is from the early part of the book. Young Donald Blad is back from the war, back from the bitter, bloody, freezing front-line. He has hated it all, the humiliation of being under orders most of all, and he is antagonistic to everyone and everything, violent and aggressive. Through a friend, another front-line soldier, he meets Jacob von Bladh, an artist, to whom he takes an intense and immediate dislike. Angered by the older man’s apparent snobbery and offensive attitude to someone from the ‘lower orders’, him. Donald Blad lashes out injury. But then Donald’s smallholder grandfather reveals that there is a family connection, the result of a shady incident in the past, which means that the two families, the ordinary working-class Blads and the distinguished von Bladhs and their Finnish branch, the Lehtisuon Lehtinens, known and famed throughout the land for their contributions to the nation, are related. The thought fills Donald Blad with amazement, curiosity and a kind of gleeful malice. The extract starts at the point at which Jacob von Blad contacts him again, and asks him to come and see him. Donald at once agrees. Thus starts a love-hate relationship which is a powerful thread throughout the book, and which also affects the whole family; Donald Blad, now Blaadh, carries on a lifelong battle with the bourgeois establishment in his climb up through its ranks, until self-realization makes him face what he has done – to his own Blad brothers, to his wives, his women, his children – and to himself. Politics, religion, commerce and art are all part of the loves and hatreds of this family, reflecting through its central character much of the turbulent story of post-war Finland.

Tags: novel

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

-

About the writer

Joan Tate (1922–2000) was a translator of primarily Swedish into English. She translated works by several Finland-Swedish authors, including Monika Fagerholm, Christer Kihlman and Oscar Parland.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.