Archive for September, 1984

The report

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kesä ja keski-ikäinen nainen (‘Summer and the middle-aged woman’) Introduction by Margareta N. Deschner

Dear Colleague,

First of all, I want to thank you and your wife for the pleasant evening I and my wife had in your summer villa in August. Briitta (since we are old acquaintances: with two i’s and two t’s, remember?) especially wants me to mention that she will never forget the half moon climbing the hill behind your sauna, surprising us with its speed. The next time we looked it was half-way up the sky! Without doubt, your fine tequila had something to do with the matter, one shouldn’t forget that. Even so, it was quite a show, just like the time a bunch of us guys had gone skiing and you bragged that you had arranged for the barn to catch fire. I hope that you and your wife – I mean Alli – will be able to visit us next winter and taste a superb Mallorca red wine called Comas, which we brought home. It is by far the best red I have ever tasted and indecently cheap to boot. I hope you will come soon. The wine won’t keep indefinitely, as you well know. We’ll save it for you. So thanks again.

Poems

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

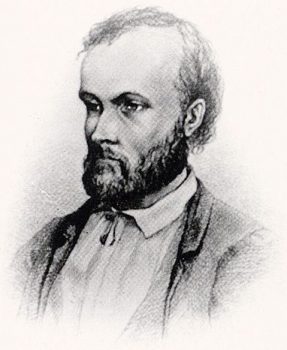

The poems of Aleksis Kivi were long considered no more than a peripheral aspect of his work. They were, as Kivi’s friend Kaarlo Bergbom wrote in a review, ‘gold that can’t be minted into coins’. The reason appears to have been Kivi’s poetic technique, which made a clear break with tradition. He did away almost completely with rhyme and instead emphasised the rhythm and musical sound qualities of words. He shortened words in a way that did not find favour with any subsequent Finnish poets. He avoided emotional expressions of patriotism and romantic love poetry; instead, he composed poems that were extended, narrative and fresco-like. Lauri Viljanen, whose 1953 study brought about a re-evaluation of Kivi’s poetry, has given them the apt soubriquet ‘epic idyll’.

The first of Kivi’s poems appeared in the Kirjallinen Kuukauslehti (‘Literary monthly magazine’) in 1866; a collection of his poetry entitled Kanervala was published the same year. Other poems appear in his novels and plays, and some have appeared in a collection after his death. Karhunpyynti (‘The bear hunt’) is from Kanervala. Its descriptive nature is typical of Kivi. The verse structure is tightly controlled but unrhyming. The winter landscape of the third verse, repeated at the end of the poem, is a ceremonious point of rest among the otherwise busy activity.

– Kai Laitinen

![]()

The Bear Hunt

The men on skis set out for the forest, a brave company

With guns and bright spears

And clamouring dogs on the leash,

With blazing eyes,

As the dawn chases gloomy Night

From the sky’s brow,

And the sun raises his head. More…