For your eyes only

11 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Photo: Steven Guzzardi / CC BY-ND 2.0

Imagine this: you’re a true bibiophile, with a passion for foreign literature (not too hard a challenge, surely, for readers of Books from Finland,…). You adore the work of a particular writer but have come to the end of their work in translation. You know there’s a lot more, but it just isn’t available in any language you can read. What do you do?

That was the problem that confronted Cristina Bettancourt. A big fan of the work of Antti Tuuri, she had devoured all his work that was available in translation: ‘It has everything,’ she says, ‘Depth, style, humanity and humour.’

Through Tuuri’s publisher, Otava, she laid her hands on a list of all the Tuuri titles that had been translated. It was a long list – his work has been translated into more than 24 languages. She read everything she could. And when she had finished, the thought occurred to her: why not commission a translation of her very own?

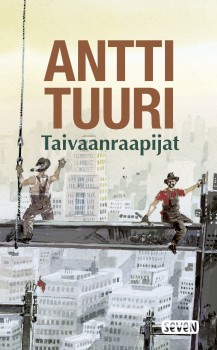

Tuuri’s publisher offered her a shortlist, from which she selected a novel called Taivaanraapijat (Skywalkers), the story of the life of a skyscraper-builder called Jussi Ketola in New York. The first step was to commission the translation of an excerpt.

The translator chosen was Jill Timbers. ‘When Otava contacted me to tell me that an individual reader was interested in commissioning the translation of one or possibly two novels,’ she says, ‘I thought someone had been partying too much. Did she have any idea of what this would cost?’

The sum was ten thousand euros. ‘I was startled when I heard the cost,’ said Bettencourt. ‘On the other hand you could spend the money on something silly like clothes. This way I would have something splendid.’

And so the project got under way. ‘Antti Tuuri is renowned for the thorough research he does for every book,’ says Jill. ‘Skywalkers tells of a community of Finnish workers building skyscrapers in New York City in the early 1900s. I learn American history from Tuuri. We follow the crew of the Finns in their daily life as they and their Mohawk co-workers balance high above NYC on the skyscrapers, court Finnish maids at midsummer celebrations carry on ribald discussions or wistfully sing Christmas hymns in the Finnish-American church. Tuuri brings to life US election politics, the bitter labor union struggles of the time, and the strong bonds that the Finns maintained with their home country. Tuuri is also known for his humor, and many of the interactions are laugh-out-loud funny.’

Cristina Bettencourt devoured Skywalkers and then wrote to say that she didn’t want it to end. ‘Guess what?’ says Jill, ‘It doesn’t!’ Skywalkers is the first book of three about the same main character; the second follows him through the bitter civil war period, where Jussi is forced at gunpoint to become a carrier of corpses, while the third sees him kidnapped and transported to the Soviet Union by the right-wing Lapua Movement. (An extract from the third volume, in Jill’s translation, can be found in the online journal Words without Borders)

Antti Tuuri commented: ‘I am really very flattered that there’s someone who wants to put money into a project like this. It also felt good that all sorts of things can happen in the world. I’ve been a writer for 25 years, and I’ve never experienced anything like it.’

We join the story at the point where the Finnish workers are invited by the architect of the building they are working on to a party in a swanky Fifth Avenue house – where they are passed off as Mohawks!

![]()

Excerpt from Skywalkers, by Antti Tuuri.

Excerpt from Skywalkers, by Antti Tuuri.

Translated by Jill Graham Timbers.

Late in the afternoon, before we finished work, Lind came up again and talked a long time with Seppälä on the lower level where the forge was. We were starting to gather the tools and cables and fasten them so the wind wouldn’t blow them all over Manhattan at night. We saw Lind leave without speaking to us. He had a habit of winking at us when he left, he wanted to show that we were all a team and he didn’t consider himself better than us even though he was the boss.

After Lind had gone, Seppälä told us what he’d been discussing on the four hundred foot level: architect LeBrun had invited all of us working on the skyscraper’s highest level to a party on Sunday at his home beside Central Park. His house was on Fifth Avenue, where rich people lived; he’d said to wear our best clothes.

Rankila said he wasn’t going to any gentlemen’s party, and I also wondered what business we’d have there. Seppälä said LeBrun wanted to show his guests real Indians and that he thought that’s what we were, too. We went down together to talk to Lind. Seppälä asked whether LeBrun thought we were all Indians and told Lind to tell him we were from across the Atlantic and the only thing we had in common with the Indians was building the skyscraper.

Jocks and Diome had come with us into Lind’s hut. They agreed to go to LeBrun’s party but lamented that they’d left their party clothes at Kahnawake, on the reservation; they would have liked to appear wearing feather headdresses and loincloths.

The rest of the week we talked a lot about LeBrun’s party, whenever the rivet guns weren’t battering, and we concluded that we would take the path of least resistance and go to the architect’s party to show his guests what skyscraper builders looked like. We agreed we would go to the party together and we would stay together there and keep an eye on each other, and we would also leave there together. Saturday was a windy day, it rained and the wind whipped water like hail into our faces. I got wet through and the beams we were supposed to walk on were so slippery we couldn’t work. Rankila talked all day about how it would be good for architect Pierre LeBrun and his guests to come see now what kind of war was being waged up here against the forces of nature and the steel and the iron. In his view LeBrun should bring all his party guests here, the women in their long gowns and the men in their waiter’s coats and tails: we’d show them what a soldier’s war is like. His sputtering made us all laugh.

At the boarding house Fiina took charge of the good clothes I would wear; she took them to her own quarters and cleaned and brushed and ironed them, and put her late husband’s gold watch in the vest pocket, with its gold chains. She said I would look very dignified and like a real financier in the Fifth Avenue house that she had rushed off to see as soon as Rankila told everyone eating dinner and Fiina and the maid that architect LeBrun had visited the top of the skyscraper and invited us to his party.

Fiina had talked about the architect’s house and party every day since. She thought it was a big thing that we had been invited as guests to a house like that which Finns usually only entered as paid help. She told me many times that she didn’t know a single man as young as me who had been invited to such a fine house as a guest.

I didn’t think that way, though, and I asked Seppälä if I really had to go with them on Sunday. Seppälä thought I should, because Lind had taken LeBrun a list with our names, and the architect might ask later why his invitation hadn’t been good enough for me. Landing on the construction worker blacklist would mean I’d never again find work on New York buildings.

So I, too, decided to go to LeBrun’s place on Sunday. We met at 7 in a bar Seppälä and Rankila knew on 59th Street. Rankila came for me at my quarters and we went together. In the bar, Seppälä told us in Finnish that we should now buck ourselves up with a glass of whiskey even though some of us belonged to the Rauhan Toivo temperance society and had taken a strict vow of abstinence. He said he himself belonged to the friends of moderation and could have a glass. Kankaanpää pointed out that in this group only Seppälä belonged to the temperance society, and everyone agreed that a glass of strength and courage would do us good. Seppälä said the same thing in English to the Mohawks. They had no difficulty agreeing to a glass of whiskey. Seppälä made us all promise that none of us would have a second drink before we entered the architect’s house and if they offered drinks there, none of us would succumb to the temptations of King Alcohol. We all promised.

…

We reached the address we’d been given, at the corner of Fifth Avenue. There was a line of cars and horse-drawn carriages on the cross street and the coachmen were settling their horses for a wait. Strang and Kankaanpää said we should have come by carriage, too, not on foot like hired men. They also discussed the carriages along the street. In their opinion they were not the carriages of poor people. I dropped behind the others, I felt I shouldn’t be the first to climb the stairs.

There were not very many stairs up to the outer door, just a few. I had imagined LeBrun’s house like Fiina’s boarding house, only bigger, and the stairs from the street to the first floor, bigger and wider. I just had time to see that this house also had a basement, and basement windows along the ground.

Seppälä went in the door first, and we others behind him. When I got inside, servants were already taking the boys’ hats. I came in last so I was able to do everything right from watching what the others did. A waiter conducted us across the large entranceway and through several rooms. He led the way and told us that the master had said to bring us straight to the garden.

I had no chance to look at the rooms before we were already in a courtyard within the house. There were people there. The one who looked like a waiter told us to wait, and left. We stood in the doorway, not knowing how to begin to speak with anyone even though we saw that they were staring at us. Seeing the men’s tailcoats, Rankila said that all the men here were dressed like restaurant waiters and the women were not on their way to any laundry room, either. We all blew softly under our breath as we looked at the outfits of the architect’s guests and at our own, but we didn’t have to stand in the doorway very long before LeBrun, who had come up to see us on the upper level of the skyscraper, arrived from somewhere in the back of the garden and shook hands with each of us and bade us welcome to the party.

LeBrun called out loudly for silence among his guests and when everyone had stopped talking and turned to look where we seven men and he were standing, he signaled the waiter, who immediately brought each of us a glass and gave the same kind of long-stemmed narrow glass to the architect himself, too.

I was quite surprised when the architect began to tell his guests in a booming voice that we were some of America’s original inhabitants, Mohawks from the Kahnawake reservation near Montreal, and we had come to New York to erect the Metropolitan Life Insurance skyscraper that he had designed. LeBrun said that together we were waging a war against nature’s harshness and steel’s hardness and earth’s gravity; many brave men had already lost their life in this war and many had been crippled for life. In this battle the Indians — in other words, us — were fighting side by side with the white men — in other words, LeBrun; we had buried the tomahawks which our fathers had brandished and together we were charging forward against our common enemy. He talked some more and when he had finished, he asked us to say a few words.

Seppälä pushed Jocks to the front. He was surprised and looked around as if he wanted to run away. LeBrun put his arm around his shoulders and pressed him to himself. LeBrun cried that he was the brother of this red man, too, and a soldier from the common front in whose frontmost trenches America’s original inhabitants were fighting as they rapidly moved the continent toward a completely new day.

Jocks began speaking in French. I don’t know what he said, but all the guests listened closely, and when Jocks had finished, LeBrun thanked him, holding onto his hand, and praised Jocks as a true man of the world and a gentleman. LeBrun said that his own ancestors had long ago come to this side of the Atlantic from France, the cradle of all civilization; he still had a lot of family there.

And so, thanks to Jocks’ speech, we all became men of the world, and LeBrun led us to a room on the first floor where there was a long table spread with all manner of food and drink. He told us to eat and drink everything on the table, to finish the platters and empty the bottles, no one else would be allowed into this room to eat. LeBrun left and we looked out the windows at the garden, and when the guests had gone inside from the courtyard, we began to eat what the host had set out.

Seppälä asked Jocks what he had said in French and where he had learned the French language. Jocks and Diome said they had both learned French in Canada, where it was taught to all the Mohawks. He said he had talked about the same thing as LeBrun, about the war that we were fighting together against everything that tried to prevent or obstruct the raising of the MetLife tower, and for that work we asked help from the spirits who lived in the wind and the rains and the hard rock, and we also asked the spirits of the sands for help, and those great spirits who lived in the Hudson River and all of their offspring. We also asked for help from the spirits of the iron and the steel, because it would be impossible to build the MetLife tower if the spirits living around us set out to oppose our work; that would mean sure death for all of us.

Seppälä asked whether Jocks had thought to mention anywhere in his speech that we were not Indians but rather had come here from Europe, from Finland, and that we were subjects of the Russian Czar. Jocks had not said anything about those things, and Seppälä told him to go tell the architect in very clear language that Finnish workers were waging war on his construction site right alongside the Indians, and that on MetLife’s highest platforms there were more Finns than any other nationality.

In Jocks’s view there was no point going to bother the host anymore because the architect had a lot to do taking care of his guests, and it would be best for us to begin eating what was spread on the table.

So we began to pile onto our plates all the good things that were offered to us. We didn’t know the names of all the foods or what animals they came from or what part of the animal they were cut from, and we didn’t know the names of all the vegetables on the platters. Most of them we did recognize, potatoes and carrots and red beets and turnips and roasts and knucklebones, and we knew some of the fish. Jocks and Diome recognized most of them but they only knew their names in French and in their own language.

I began to taste what was on the table. Seppälä believed that today we could make an exception to the temperance society rules and drink a glass of wine, even though we had already had a glass of whiskey in the bar, which the old rules did permit. Rankila pointed out that we had already gotten a glass of champagne in the garden, which was also considered a sparkling wine and among the beverages in which the spirit of the bottle resided. We agreed that we wouldn’t tell anyone that we had a third drink.

Jocks studied the bottles. He found a corkscrew and opened all the bottles of wine, of which there were many on the table, sniffed each bottle and then poured us glasses. We picked them up. Seppälä said he did not agree with everything LeBrun said about the Indians’ and white men’s war against matter and the laws of nature, but he wanted to wish us an enjoyable evening and he reminded us of the pact we had made in the bar, that we would take care of each other and stay together in this skirmish, too.

Tags: translation

No comments for this entry yet