Non-fiction

At your service

19 March 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Melancholy man: detail of the almsman in Pomarkku, carved by Artturi Kaseva in the 1920s. Photo: Aki Paavola

Old men carved of wood have stood outside churches since the 17th century, begging for money to be given to the poor and the sick of the parish. These almsmen, or men-at-alms, mostly represented a disabled soldier; the tradition is not known elsewhere. Some 40 of the still surviving almsmen (there is one almswoman) were assembled for an exhibition in Kerimäki – in the world’s largest Christian wooden church – in summer 2013. The surviving specimens were hunted down and photographed by Aki Paavola for the book Vaivaisukkojen paluu (‘The return of the almsmen’). Otso Kantokorpi asks in the title of his introduction: are men-at-alms pioneers of ITE (from the words itse tehty elämä, ‘self-made life’; the English-language term is ‘outsider art’) or a disappearing folk tradition?

Many a church or belfry wall, particularly in Ostrobothnia, has been decorated – and is often still decorated – with a wooden human figure. Often they stand beneath a decorative canopy, sometimes accompanied by an encouraging phrase: He that hath pity upon the poor lendeth unto the LORD. They have been called men-at-alms or boys-at-alms. More…

Below and above the surface

13 March 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Fårö, Gotland, Sweden. Photo: Lauri Rotko

The Baltic Sea, surrounded by nine countries, is small, shallow – and polluted. The condition of the sea should concern every citizen on its shores. The photographers Jukka Rapo and Lauri Rotko set out in 2010 to record their views of the sea, resulting in the book See the Baltic Sea / Katso Itämerta (Musta Taide / Aalto ARTS Books, 2013). What is endangered can and must be protected, is their message; the photos have innumerable stories to tell

We packed our van for the first photo shooting trip in early May, 2010. The plan was to make a photography book about the Baltic Sea. We wanted to present the Baltic Sea free of old clichés.

No unspoiled scenic landscapes, cute marine animals, or praise for the bracing archipelago. We were looking for compelling pictures of a sea fallen ill from the actions of man. We were looking for honesty. More…

Human destinies

7 February 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

To what extent does a ‘historical novel’ have to lean on facts to become best-sellers? Two new novels from 2013 examined

When Helsingin Sanomat, Finland’s largest newspaper, asked its readers and critics in 2013 to list the ten best novels of the 2000s, the result was a surprisingly unanimous victory for the historical novel.

Both groups listed as their top choices – in the very same order – the following books: Sofi Oksanen: Puhdistus (English translation Purge; WSOY, 2008), Ulla-Lena Lundberg: Is (Finnish translation Jää, ‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms, 2012) and Kjell Westö: Där vi en gång gått (Finnish translation Missä kuljimme kerran; ‘Where we once walked‘, Söderströms, 2006).

What kind of historical novel wins over a large readership today, and conversely, why don’t all of the many well-received novels set in the past become bestsellers? More…

Like it, or else

23 January 2014 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

Hitting the ‘like’ button is not only boring but also working its way from Facebook deeper into society, says Jyrki Lehtola. Surely there must be some other way of solving the world’s problems?

At the end of the autumn the theatre critic of the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper panned Sofi Oksanen’s stage adaptation of her novel Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the doves disappeared’, 2013).

That’s life. Artists struggle with their projects, sometimes for years. Then a critic takes a glance at the result and crushes it in a matter of hours.

Then there’s a huff about unfairness, the use of power and all the things artists blow off steam about when they feel that their creations have been treated unfairly. The debate is held between injured authors and sometimes the critic, but generally few others participate, and just as well. More…

Verse and freedom

16 January 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

Aale Tynni (1913–1997). Photo: WSOY

Finnish poetic modernism, which with its freedom of rhythm came to dominate the literary mainstream of the 1950s, posed a particular challenge to the poets of the classical metrical and romantic poetic tradition. Aale Tynni (1913–1997) is not a poet of any one school or form, but rhythm is the deepest foundation of her poems, whether expressed in metre, free verse or the speech rhythms that characterise some of her poems of the 1950s and 60s, as well as those of her final years.

An Ingrian Finn, Tynni left Ingermanland near Petersburg for Finland as a refugee after the First World War, in 1919. The war and the period of uncertainty that followed it are present in her poems as an allegory, sometimes appearing as a dance of death or a carnival. At other times they emerge in the myth of Phaethon, who with his sun chariot is in danger of throwing Mother Earth off her axis, or as a game of chess in which God and the angel Gabriel play with the planets and moons as pieces. The poet makes use of mythic and cosmic references to widen her scope and to portray Man in the stages of history and the present age. More…

Reading matters? On new books for young readers

9 January 2014 | Articles, Children's books, Non-fiction

The Pixon brothers don’t read books, they love the telly: story by Malin Kivelä, illustrations by Linda Bondestam (Bröderna Pixon och TV:ns hemtrevliga sken, ‘The Pixon brothers and the homely shimmer of the telly’)

Finnish picture books for children have long been reliable export goods around the world. In the last few years, a number of novels for children have come along in their wake: works by authors such as Timo Parvela and Siri Kolu have been translated into a good many languages.

Now young adult literature has also blazed a trail on to the international market – in what also seems to be almost a matter of precision timing with regard to the Frankfurt Book Fair 2014. Finnish publishers have been investing in their home-grown lists of children’s and young adult books ever since the turn of the millennium, and now the time has come to harvest the fruits of their long-term efforts.

Not so weird?

12 December 2013 | Non-fiction, Reviews

Johanna Sinisalo. Photo: Katja Lösönen

Johanna Sinisalo’s new novel Auringon ydin (‘The core of the sun‘, Teos, 2013), invites readers to take part in a thought experiment: What if a few minor details in the course of history had set things on a different track?

If Finnish society were built on the same principle of sisu, or inner grit, as it is now but with an emphasis on slightly different aspects, Finland in 2017 might be a ‘eusistocracy’. This term comes from the ancient Greek and Latin roots eu (meaning ‘good’) and sistere (‘stop, stand’), and it means an extreme welfare state.

In the alternative Finland portrayed in Auringon ydin, individual freedoms have been drastically restricted in the name of the public good. Restrictions have been placed on dangerous foreign influences: no internet, no mobile phones. All mood-enhancing substances such as alcohol and nicotine have been eradicated. Only one such substance remains in the authorities’ sights: chilli, which continues to make it over the border on occasion. More…

Mad men

5 December 2013 | Non-fiction, Reviews

lllustration from the cover of Hulluuden historia

Hulluuden historia

[A history of madness]

Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2013. 456 pp.

ISBN 978-952-495-293-4

€39, hardback

The Hippocratic Oath’s principle, primum non nocere – ‘first, do no harm’ – has been particularly difficult to apply in practice for doctors who have devoted themselves to sicknesses of the soul.

The breaking with this principle is the first thing to strike the reader in Professor of Science and Ideas Petteri Pietikäinen’s book, Hulluuden historia, which is overflowing with ideas.

This could be due to the vast amount of information contained within the book, combined with its slightly chaotic structure. It skips between a chronological and thematic narratives, and the author’s own involvement in his text varies, meaning that the text itself swings between vigorously discursive, and something that is little more than a sluggish retelling. Taking in everything Pietikäinen wants to say is difficult; the reader inevitably begins to grope for exciting details, and there are of course plenty of those to be found.

The sad thing is that the development of mental health care has not advanced steadily at all from its dark and ignorant beginnings towards a brighter and more enlightened present. Setbacks, especially concerning patients’ safety, have been many. Even if we ignore centuries of exorcisms, abuse, and care in the form of incarceration, punishment, and physical punishment, the 20th century has a wealth of gruesome examples to offer. More…

Decisions, decisions: the fate of virtual literature

28 November 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

Once upon a time: ‘Boyhood of Raleigh’ by J.E. Millais (1871). Wikipedia

In an era of ‘liveblogging’‚ we are all storytellers. But what’s the story, asks Teemu Manninen

One score of years ago, when the internet was new, the cultural critics of the time were fond saying that it would usher in a new utopia of free distribution of information: we would be able to read everything, know everything and share everything anywhere and every day.

Truly, they told us, we would become enriched by the internet to the point of not knowing what to do with all that wealth of knowledge, the amount of connections between us and the ever-increasing online availability of anyone with everyone, every waking hour.

Now that we really do have this always-on connectivity, you will indeed be available every waking hour: you will update your status, check your inbox, post pics and be available for chatting, texting, a quick email and a message or two, just to make sure no one is offended by your unreachability, since – from experience – a week’s worth of not tweeting or facebooking can make someone think that something serious has happened, or that you don’t even exist anymore. More…

That which simply is

24 October 2013 | Non-fiction, Reviews

Henrika Ringbom. Photo: Curt Richter

Henrika Ringbom

Öar i ett hav som strömmar

[Islands in a flowing sea]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2013. 78 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-3218-2

€21, paperback

Henrika Ringbom’s new collection of poems is emotionally touching and formally sophisticated – something only the very best poetry can manage. Ringbom is an experienced author whose output since her debut in 1988 has included five collections of poetry and two novels; even so, it feels as if she has taken another step forward in her writing with this latest volume.

The focal point is the loss of a beloved mother. The title, which translates as ‘Islands in a flowing sea’, emphasises the fleeting nature of all life, and the book radiates sorrow more than anything else. There has always been an intellectual, distancing quality to Ringbom’s writing. That stands her in good stead here, preventing the book from becoming too private and introverted, despite its highly personal themes. More…

What have brains got to do with it?

17 October 2013 | Columns, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

Pondering his changing profession once again, columnist and media critic Jyrki Lehtola feels compelled to present a brief history of the media

Not long ago a certain media company invited me to participate in a panel on brainprints.

I didn’t know what they were talking about, so I agreed. At most I thought it was about the engram left in our collective psyche that yes, we used to have this sort of print media thing that told us what the world was like.

And then we didn’t – look at this picture of print media on my iPad, kids, isn’t it cute?

That wasn’t what it was about at all. Brainprint means all the ways the media can influence us as consumers. In other words, this is one more conversation the media has with itself to convince itself that it has a role to play.

There we sat around a long table once again talking about whether the media is a mirror or a window when maybe we should have been talking about the pile of glass on the ground and whether someone shouldn’t clean it up before someone hurts themselves. More…

Is this all?

10 October 2013 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Earth. Andrew Z. Colvin/Wikimedia

In today’s world, many people find that it is not the lack of something that is problematic, but excess: the same goes for knowledge. According to professor of space astronomy, Esko Valtaoja, knowledge should contribute to the creation of a better world. His latest book is a contribution to the sum of all knowledge; over the course of two hundred pages Valtaoja delves deep into the inner space of man by taking his reader on a brief tour of the universe. Extracts from Kaiken käsikirja. Mitä jokaisen tulisi tietää (‘A handbook to everything. What everybody should know’, Ursa, 2012)

Whatever god you bow down to, you’re probably worshipping the wrong god.

The above is almost the only completely certain thing that can be said about religion, and even it does not encompass any deep truth; it’s just a simple mathematical statement. The world’s biggest religion is Roman Catholicism, which is confessed, at least nominally, by 1.1 billion people. If the Roman Catholic god were the true god, the majority of people in the world are therefore worshipping a false god. (According to the official stance of the Catholic church, the other Christian denominations are heresies, and their believers will be condemned to perdition: extra ecclesiam nulla salus. This inconvenient truth is, understandably, politely bypassed in ecumenical debate. But even if all those who call themselves Christians were counted as worshipping the same god, two thirds of the world’s population are still knocking at the wrong door.)

If you’re a religious person, don’t worry; I’m not blaspheming. And if you’re a campaigning atheist, hang on a minute: all I want to do is to find a clear and undisputed starting point to consider what it is we’re talking about when we speak of religion. More…

Girls just want to have fun

3 October 2013 | Essays, Non-fiction, On writing and not writing

In this series, Finnish authors ponder the complexities of their profession. Susanne Ringell describes her work as sailing on sometimes stormy seas – without a skipper certificate, but with conviction

We are such stuff as dreams are made on; / and our little life is rounded with a sleep. (William Shakespeare, The Tempest.) In Swedish – my mother tongue and the language in which my pencil writes – the play is called Stormen, ‘The storm’. There are a lot of storms on the sea of dreams. The sky suddenly grows dark, and deceptive whirlwinds blow up, there are cold shivers and tornadoes, there is the Bermuda Triangle and the mighty chasm of the Mariana Trench. In its southern part is the world ‘s deepest marine environment, Challenger Deep, 11 kilometres. Our boats are small and fragile, and it ‘s a miracle they haven’t capsized more often.

It’s a miracle that in spite of it all we still so frequently reach our home harbour, that we arrive where we were bound for. Or somewhere else, but we do get there. We come ashore, we come ashore with what we set our minds on. More…

Cut time, paste space

12 September 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

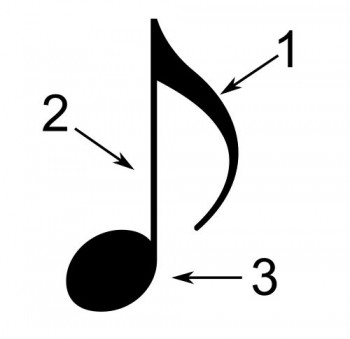

Back to basics. Parts of a musical note. Picture: Wikimedia

How different are the art of words and the art of sounds, author Teemu Manninen ponders, as he unexpectedly finds himself in the role of a musician in a performance. Time, space or both?

Some time ago I got the chance to participate in an unusual concert – as a performer: six players, myself included, were grouped around a table with a triangle in one hand and a glove in the other. Pieces of dry ice and a bucket of water were placed in front of each of us.

The performance began: we took a piece of dry ice and pressed it against the triangle. As the metal cooled, it burned through the ice, releasing gas, which in turn made the metal vibrate very fast. This produced a keening sound that filled the room. More…