Archives online

Landscapes of the mind

Issue 2/1986 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

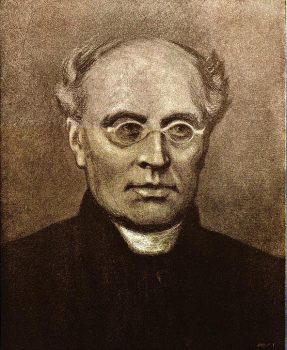

Tuomas Anhava. Photo: Otava

In his book Suomalaisia nykykirjailijoita (‘Contemporary Finnish writers’), Pekka Tarkka describes Tuomas Anhava’s development as a poet as follows: In his first work, Anhava appears as an elegist of death and loneliness; and this classical temperament remains characteristic in his later work. Anhava is a poet of the seasons and the hours of the day, of the ages of man; and his scope is widened by the influence of Japanese and Chinese poetry. As well as his miniature, crystalclear, imagist nature poems, Anhava writes, in his Runoja 1961 (‘Poems 1961’), brilliant didactic poems stressing the power of perception and rebuffing conceptual explanation. The mood in Kuudes kirja (‘The sixth book’, 1966) is of confessionary resignation and intimate subjectivity.

Anhava’s literary inclinations reflect his most important translations, which include William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1959), selections of Japanese tanka poetry (1960, 1970, 1975), Saint John Perse’s Anabasis (1960), a selection from the works of Ezra Pound, published under the title Personae, and selections from the work of the Finland-Swedish poets Gunnar Björling and Bo Carpelan.

![]()

Song of the black

My days must be black,

to make what I write stand out

on the bleached sheets of life,

my rage must be the colour of death, to make my black love stand out,

my nights must be summer white and snow white,

to make my black grief burn far,

since you're grieving and I love you

for your undying grief.

Let the sun's rolled gold gild dunghills,

let the moon's blue milk leak out till it's empty,

we're not short of those.

The obscure black darkness of the cosmic night

glitters on us enough.

From Runoja (1955)

The Cheap Contractor

Issue 2/1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Kauan kukkineet omenapuut (‘Long-blossoming apple trees’, 1982). Introduction by Arto Seppälä

The men who delivered the hot-water cylinder offered to do the installation as well. I asked how much it would be. They lolled about a bit, exchanged a few private looks, pretended to be thinking. Then one of them fired off a sum. It was three times the quotation I’d already had. They didn’t even look at the location. I told myself I wouldn’t even go to the end of the road with big-dealers like these.

The same evening I rang up ‘a little man’ and told him he could get started as soon as it suited him.

The cheap contractor turned up a couple of days later, driving an elderly van into the yard. I went out. He’d sat himself down in a garden chair near the white lilacs. The morning sun only partially reached there; so half his body was in shade, looking colder than the sunny half. More…

Six letters

Issue 1/1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Tainaron (1985). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The whirr of the wheel

Letter II

I awoke in the night to sounds of rattling and tinkling from my kitchen alcove. Tainaron, as you probably know, lies within a volcanic zone. The experts say that we have now entered a period in which a great upheaval can be expected, one so devastating that it may destroy the city entirely.

But what of that? You need not imagine that it makes any difference to the Tainaronians’ way of living. The tremors during the night are forgotten, and in the dazzle of the morning, as I take my customary short cut across the market square, the open fruit-baskets glow with their honeyed haze, and the pavement underfoot is eternal again.

And in the evening I gaze at the huge Wheel of Earth, set on its hill and backed by thundercloud, with circumference, poles and axis pricked out in thousands of starry lights. The Wheel of Earth, the Wheel of Fortune… Sometimes its turning holds me fascinated, and even in my sleep I seem to hear the wheel’s unceasing hum, the voice of Tainaron itself. More…

Emotional transgressions

Issue 4/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Three extracts from the novel Harjunpää ja rakkauden lait (‘Harjunpaa and the laws of love’). Introduction by Risto Hannula

It was a few minutes to two, and Harjunpää was still awake, lying so close to Elisa that he could feel her warmth. He kept his eyes open, staring into the night through the crack between curtains. Once again the boiler of the central heating plant started up, and the smoke began to rise like a stiff column in the cold. Another fifteen minutes had passed, and morning was a quarter of an hour closer. He squeezed his eyes shut and tried to concentrate on Elisa’s breathing and the sleepy snuffling of the girls, but his thoughts still wouldn’t leave him in peace. Inexplicably, he felt there was something wrong, that the darkness exuded some kind of threat, that he’d left something undone or had made some kind of mistake.

He swung his feet onto the floor and got up as quietly as he could. But all his care was wasted, he should have known that.

‘What’s the matter?’ Elisa asked sleepily.

‘I just can’t get to sleep.’

‘Again … ‘

‘I can’t help it. I wonder if there’s a bottle of brew left.’

‘Sure. But listen …’

Pipsa turned over in her crib, rattling the sides, groped around a bit and began to suck her pacifier so you could hear the quiet sucking noises.

‘Yeah?’

‘Maybe you could see a doctor. You could ask for some mild … ‘ More…

Poems

Issue 4/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

Birds of passage

Ye fleet little guests of a foreign domain,

When seek ye the land of your fathers again?

When hid in your valley

The windflowers waken,

And water flows freely

The alders to quicken,

Then soaring and tossing

They wing their way through;

None shows them the crossing

Through measureless blue,

Yet find it they do.

Unerring they find it: the Northland renewed,

Where springtime awaits them with shelter and food,

Where freshet-melt quenches

The thirst of their flying,

And pines’ rocking branches

Of pleasures are sighing,

Where dreaming is fitting

While night is like day,

And love means forgetting

At song and at play

That long was the way. More…

Poems

Issue 3/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by Pertti Lassila

If you come to the land of winds, to the bottom of the sea,

there are few trees, plenty of icy wind

from shore to shore.

You can see far

and see nothing.

Around you screech the newborn plains

still wet from fog

but clear as a dream

at the edge, the sea

beneath, the deep earth

above, the wide expanse

shouts to you and to the plains

about being

it looks at you and asks

When we returned home

and leaned against the long table

we could see the simple grain of the wood

and our weariness turned into knowledge

of why we had had to go away:

to come back to see the uncharted patterns

in the table at home.

From Lakeus (‘The plain’, 1961)

Among the ice floes

Issue 3/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

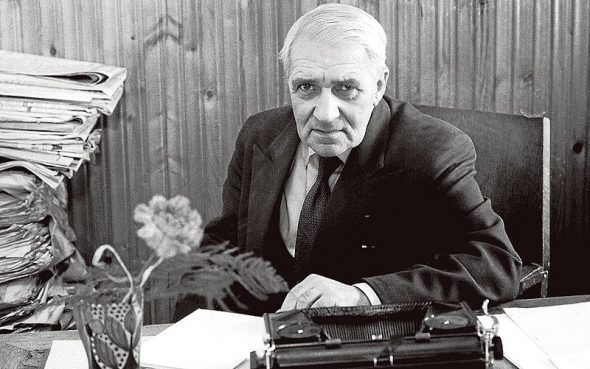

Alpo Ruuth. Photo: Sakari Majantie / Tammi

Alpo Ruuth came across the diary of a member of the Finnish crew of ten men in the Whitbread Round-the-World sailboat race of 1981-1982, and Ruuth, a sailor himself, used that diary as the basis for his novel, 158 vuorokautta (‘158 days’, 1983). It is the story of a great adventure which takes place with the help of ultra-modern equipment and yet involves confrontation with elemental nature, the dangerous power of the southern seas. Ruuth does not use the actual names of the crew, but has taken the view of the fictional crew member who is able to offer ironic comments on what he observes. The book portrays the relationships among the crew under the cramped and difficult conditions of the long voyage. As the extract begins the yacht is in the Southern Ocean, close to the Antarctic coast, making its way towards Auckland, New Zealand.

An extract from 158 vuorokautta (‘158 days’)

Around noon we run into a blizzard. On deck they shout down that a wind has got up. Below, we wake hurriedly from our afternoon naps and start pulling on clothes against the tough weather outside. It’s quite a business in our cramped quarters, and every now and then someone loses his footing and falls as the boat pitches. Cursing is the only medicine for bruises. One by one the boys go up to help change sails; at the bottom of the steps there are excesses of politeness: after you, sir; no no, after you. Up they go, all the same. More…

At the sand pit

Issue 3/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

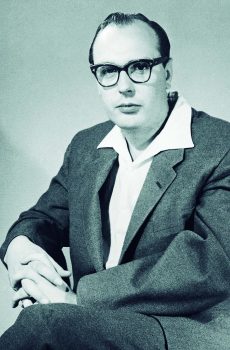

Antti Tuuri. Photo: Jouni Harala

‘After nearly 40 years of observing the Ostrobothnians, I am convinced that they have certain characteristics which explain the historical events that took place there and which also shed light on the region today. I do not know how these characteristics develop, but it appears that heredity, economic factors and even the landscape form the nature of people. Everywhere people who live in the plains are different from those who dwell in the mountains, and from those who fish the archipelagos,’ writes the author Antti Tuuri, himself an Ostrobothnian.

Antti Tuuri’s Pohjanmaa (‘Ostrobothnia’, 1982), which last January was awarded the Nordic Prize for Literature, has now been translated into each language of the Nordic countries. Tuuri’s novel describes the events of one summer day in Ostrobothnia, on the west coast of Finland, where a farming family, the Hakalas, has gathered for the reading of the will of a grandfather who emigrated to the United States in the 1920s.

The inheritance itself is insignificant, but it has brought together the four grandsons, with their wives and children. The story is narrated from the point of view of one of the brothers. The women of the family remain inside while the men take out an automatic pistol which has been kept hidden away since one of them smuggled it home from the Continuation War. The men go off to a sand pit to do some shooting and to drink some illegal home brew. There they meet their former schoolteacher, who joins in with their drinking and shooting. Some surprising events take place as the day’s action unfolds, and Tuuri’s narrator views them in an unsentimental way, describing them matter-of-factly and at times with ironic humour. The men recall the violent history of Ostrobothnia, the years of the Civil War and the right-wing Lapua movement of the 1930s.

The Nordic Prize jury commented that the novel ‘portrays the breaking up of the old society, and conflicts between generations as well as between men and women.’ Tuuri has constructed his novel on conflicts, and the result is a highly dramatic narrative.

![]()

An extract from Pohjanmaa (‘Ostrobothnia’)

A Finnish hound dog came out of the woods just beyond the sandpit, stopped at the edge of the pit and started to bark at us. The boys quickly began putting the weapon together. Veikko yelled that you were allowed to shoot a dog running loose in the woods out of hunting season. He kept asking me for cartridges; he’d shoot the dog right away, before it could tear to pieces the young game birds that couldn’t fly yet. I told him to shut up. Seppo finished putting the automatic pistol together and gave it to me. I ran to the car, put the gun down on the floor in front of the back seat and tossed a blanket over it.

When I got back, I saw the teacher coming out of the woods over by the pit. He snapped a leash on the dog and started towards us through the pine grove. The boys sat down around the campfire and began taking swigs of home brew from their cups. More…

Poems

Issue 2/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by Bo Carpelan

A flower beckons there, a secent beckons there, enticing my eye. A hope glimmers there. I will climb to the rock of the sky, I will sink in the wave: a wave-trough. I am singing tone, and the day smiles in riddles.

*

Like a sluice of the hurtling rivers I race in the sun: to capture my heart; to seize hold of that light in an inkling: sun, iridescence. In day and intoxication I wander. I am in that strength: the white, the white that smiles.

*

To my air you have come: a trembling, a vision! I know neither you nor your name. All is what it was. But you draw near: a daybreak, a soaring circle, your name.