New from the archives

Tritonus

Issue 3/1976 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry | Added 2 November 2017

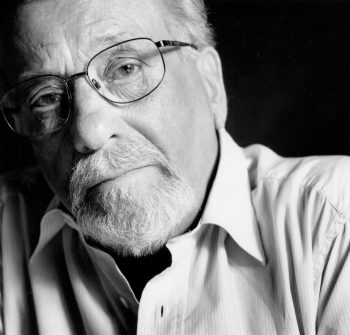

Pentti Saaritsa playing chess. Photo by Otso Kantokorpi, 2006.

Pentti Saaritsa (born 1941), author of six collections of poetry, is one of Finland’s leading left-wing poets, who writes about a wide range of individual and social themes. An outstanding translator, he has had a major role in making Latin American literature, especially the work of Miguel Angel Asturias and Pablo Neruda, known and admired in Finland. He also translates from Russian. The first five poems below have been taken from his latest collection Tritonus (‘Tritone’, Kirjayhtymä 1976), and the last two from his Syksyn runot (‘Autumn poems’, Kirjayhtymä 1973). His poems have appeared in various anthologies abroad and are now being translated into Swedish, English and French. Pentti Saaritsa is a member of the editiorial board of Books from Finland.

![]()

1

From the bowels of each apartment house

always that one unknown sound is borne.

Sometimes like drily dripping water, sometimes

as a stone might bite a lump out of itself,

Or a child awake in the dark might learn the word hair.

And a tenant listens, makes a note of it

perhaps to punctuate the interrupted writing of his consciousness

when it makes him restless:

What now, again so soon, is it coming from me

or from the dead building.

An alarm-bell. Did anyone else hear? More…

In the early hours

Issue 1/1976 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose | Added 2 November 2017

An extract from Dyre Prins (‘Sweet Prince’, 1975). Introduction by Ingmar Svedberg

Donald Blaadh, a retired businessman, has been called to visit an influential acquaintance in the middle of the night.

He was sitting in the library, listening to Shostakovich, the Leningrad Symphony. The slow crescendo. The insistent march rhythm. Dogged endurance. Indomitability. He switched it off when I came in.

“I can’t sleep,” he said.

“Neither can I.”

He ignored the ironic undertone. “Shostakovich sharpens the decisionmaking faculties, the way chess sharpens the wits,” he said. “A sort of exercise routine … but I forgot, you don’t play chess.”

“No, but I do play the gramophone.”

“To-day I’m going to start you off with a quiz: whose immortal words were these, ‘Minerva’s owl never takes to the air till twilight is falling’?”

“I don’t know.” More…

Front-Line Tourists

Issue 3/1976 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose | Added 2 November 2017

An extract from the novel Nahkapeitturien linjalla (‘On the tanners’ line’, 1976)

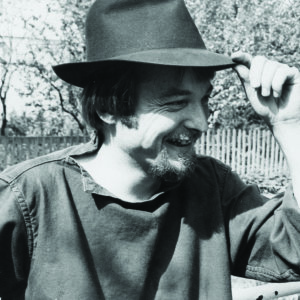

Paavo Rintala (born 1930) published his first novel in 1954 and since then has brought out a new book almost every year. A merciless critic of the myths surrounding certain national figures and events, he has written about Marshal Mannerheim, against attempts to glorify war, and the ‘inevitability’ of Finland’s involvment in the German Barbarossa plan. He has made considerable use of reportage technique to produce anti-war documentaries and in more recent years worked with international subjects.

His books have been widely translated and are popular in East and West Europe. Paavo Rintala’s novel Sissiluutnantti (‘Commando Lieuenant’, Otava 1963) and its reception were the subject of a book by the ltterary critic Pekka Tarkka (Paavo Rintalan saarna ja seurakunta. ‘Paavo Rintala’s sermon and congregation’, Otava 1966). Paavo Rintala is chairman of the Finnish Peace Committee. The passage below is taken from Nahkapeitturien linjalla (‘On the tanners’ line’, Otava 1976) in which he again turns his attention to the war years. Rintala looks at the events of the years leading up to the war and the course of the war itself through the eyes of many different people – from the leading politicians of the day to the ordinary soldier.

The novel has already been acclaimed as the monument to the ‘unknown soldier’ of the Winter War.

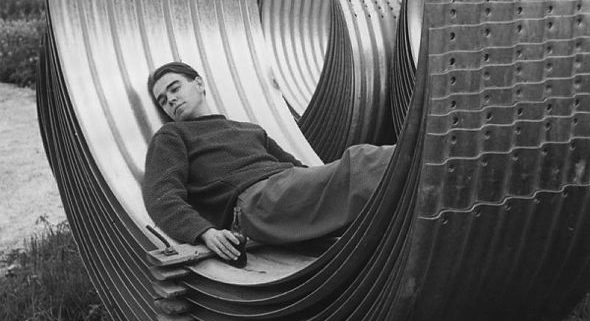

![]()

Hessu duly presented himself at the Viipuri office of the Army Information Department (Visitors’ Escort Section), where it was implied that the expected visitors were Very Important People and that a singular privilege was being conferred upon Hessu and such front-line troops that the party might visit. Although His Excellency Field-Marshal Mannerheim made it a rule never to allow front-line visits by ordinary journalists or even by special correspondents, these gentlemen were, it seemed, such influential people that H.E. had agreed to their visit without demur. “You understand, Padre, what a great responsibility this will be for you? These are very high-up people.” More…

Sensitivity session

Issue 2/1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose | Added 25 October 2017

An extract from the novel Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Taito Suutarinen knew quite a bit about Freud. Where Mannerheim’s statue now stands, Taito felt that there ought instead to be an equestrian statue of Sigmund Freud. It would be like truth revealed.

Freud, urging on his trusty stallion Libido, would be clad from head to foot in sexual symbols – hat, trousers, shoes: one hand thrust deep into his pocket, the other grasping a walking-stick. The stick would point eloquently in the direction of the railway tracks, where the red trains slid into the arching womb of the station.

Taito had also attended a couple of seven-day sensitivity training courses, where people expressed their feelings openly, directly and spontaneously. By the end of the first course Taito was so direct and spontaneous that he couldn’t get on with anybody. By the end of the second he was so open that everyone was embarrassed. Every member of the group had cried at least once, except the group leader. Never before had Taito witnessed such power. He could not wait to found a group of his own. Taito’s group met in a basement room, where they reclined on mattresses to assist the liberation process. Everyone was free to have problems, quite openly. You were not regarded as ill: on the contrary, if you realized your problem you were more healthy than a person who still thought he mattered. Moreover, as Taito, fixing you with his piercing gaze, was always careful to emphasize, every problem was ultimately a sexual problem. Taito would spontaneously scratch his crotch as he spoke, making it clear that he himself had virtually no problems left. More…

A Wedding Dance

Issue 1/1977 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose | Added 25 October 2017

An extract from the novel Kivenpyörittäjän kylä (‘The stoneroller’s village’). Introduction by Hannes Sihvo

Pölönen got up and went over to his accordion, which he had dumped beside the juke-box. He walked with his stocky trunk thrust forward, his hands dangling; the wallet he had crammed into his hip-pocket, constrained to follow the curve of his fat buttock, made an unsightly bulge suggestive of some kind of excrescence. With a vigorous shoulder movement he hoisted the instrument into position. At once the neck of the bottle in his inside pocket came into view, emitting spurts of foam, and it was some time before he noticed it and managed to nudge it back so that it would lean the other way. Scarlet in the face and streaming with sweat, glaring angrily and doing his utmost to avoid looking in the direction of the assembled company, Pölönen drew some air into the bellows and tried out various notes and chords, fingering the keyboard with an airy nonchalance intended to suggest that he was a complete master of his instrument. All eyes were turned upon this podgy, fair-haired man, with the suit that was far too tight across the shoulders and under the armpits, the very small and rather crumpled tie, the tapering trouser legs with shiny bulges at the knees. The warming-up process continued for what seemed an unconscionably long time, and a certain amount of shuffling and coughing began to be audible; old Nestori Pölönen gazed stiffly down at his shoes, and Saara’s movements, as she busied herself behind the coffee-table, became more and more fidgety. More…

Mishaps, perhaps

Issue 3/1976 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry | Added 9 May 2017

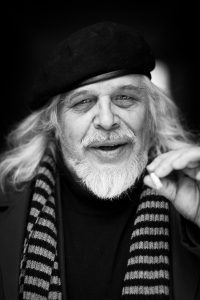

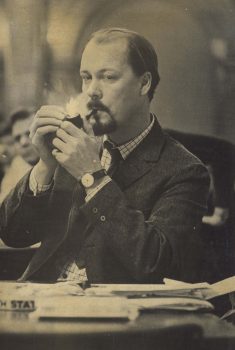

Jarkko Laine. Photo: Kai Nordberg

Jarkko Laine (born 1947) writes both prose and verse. He is the author of several hilarious and highly imaginative novels and a pioneer of the generation of Finnish underground poets. One of the most productive of younger Finland’s poets, he draws on the language and forms of mass commercial entertainment, comics, and pop music to write about people of today.

He is currently the editorial secretary of the literary periodical Parnasso. The poem below is from his latest collection Viidenpennin Hamlet (‘Fivepenny Hamlet’, Otava 1976)

![]()

1

In Turku again

the taxi’s travelling East Street

whose wooden sides have gone,

the radio’s laryngeal with static, VHF, the driver’s

telling me the tale,

the ice hockey season’s on us already,

even though there’s rain, green in the park,

I’m staring at the lifted houses

stuffed with sleeping persons,

the landmarks are going out one by one, all of them,

you might as well be

in the middle of the sea in a rubber dinghy,

soon I shan’t recognize anything here but

the cathedral, the castle,

my own name in the telephone directory. More…

Poems

Issue 3/1977 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry | Added 5 April 2017

Poems from I de mörka rummen, i de ljusa (‘In the dark rooms, in the bright ones’, 1976). Introduction by Kai Laitinen

1

He covers his grey floor with glowing carpets.

He has bought them cheap. No one sees they are fakes

except The Great Specialist – but he never comes.

He covers the windows with curtains like waves of silk

and wraps himself up in his food with a blind look of hunger.

Those who follow him – the wife, the children – have to run.

He goes quickly through the dark as though it were hounding him.

He is right: it is hounding him, it catches up with him

when he wakes defenceless in the night. He is abandoned:

all the time there is a noise in the rooms, a burglary,

he is afraid and does not move but in the dark holds

his hand to his eyes, it is cold and strange.

Each day he goes to his life and comes from it.

He is like a wagon. A wagon has its uses.

It trundles heavily past sidestreets and down to the harbour.

He stops: it is light over the sea, a light

hidden by clouds. As though he had seen it once, before.

What he sees is nothing, stretching far away.

There are waves, but they are all standing still. More…

Poems

Issue 4/1977 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry | Added 30 March 2017

Poems from Tanssilattia vuorella (’The dancing-floor on the mountain’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

I

Having studied

Krinagoras

the flower of Philippos’ wreath

under the vaults in a cool library far away in silence

I have gone to see the boat how it is coming on

whether it will be in working order next summer

we have no strong men

have sat on the beach-hut steps thinking of him

the politician the negotiator:

poetry is a holding of council, an art of negotiation More…

Meetingplace the year

Issue 2/1978 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry | Added 28 March 2017

Poems from Kohtaamispaikka vuosi (‘Meetingplace the year’, 1977). Introduction by Mirjam Polkunen

1.

I look in from the gateway

there are children, there in the yard playing.

They look small from here, remote.

From the years

I have walked past this gateway,

there they are: five, six.

The same number.

They have a ball in the air, they yell at it.

Silly that I still here too

remember you,

I could be the same age now.

More…

The Onlookers

Issue 3/1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose | Added 28 March 2017

A short story from Naisten vuonna (‘In women’s year’, 1975). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

The two elks came out on to the road through a gap between timber sheds. They began to cross the road, and the larger one was very nearly run into by a car. Cars stopped and horns tooted, till the elks turned and made off towards the harbour. Several cars swung round and drove along the cinder track in pursuit of the animals.

The elks headed across the rubble towards the power station; after circling some stacks of railway sleepers, they ended up on the flank of a coalheap sixty feet high. The cars pulled up and their occupants poured out, shouting that the elks wouldn’t go that way, it was a dead end. The elder of the two elks had indeed sensed this, and they moved off to the right, skirting the coal-heap and emerging among the timber-stacks. By this time the first cyclists and pedestrians had arrived on the scene.

“They’ll break their legs,” said a pedestrian to a motorist. “There’s all kinds of junk lying about.” More…

Poems

Issue 1/1978 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry | Added 9 March 2017

Poems from Laulu tummana tulevi (‘The song comes darkly’, 1976). Introduction by Pentti Saaritsa

1

I have longed for you

as the burning heath for rain,

I have asked for you

as fingers of moss for shade,

I have yearned for you

as the dusty mind for tears,

and I have loved you

as distant lightning the dark,

I have been in you

as flowering pine in the wind.

The blue will-o’-the-wisps dance,

strangers stitching happiness.

Silvery the spring mornings,

the trumpets bright in summer,

the autumns cranberry-red,

the white legend of winter. More…