Search results for "2010/02/let-us-eat-cake"

Mutts and mongrels of architecture

28 November 2013 | This 'n' that

Uudenmaankatu Street 42: a mixture of architecture from 1865–66 and 1905–07

Low-rise wooden buildings in the late 19th-century small town of Helsinki began to disappear as they were beginning to be replaced by houses built of stone. Last century wars and economic interests further changed the façades of Helsinki.

The oldest buildings may contain several generations of constructions, clearly visible or more discreet. In the past houses have been treated in a way which is no longer acceptable.

They were altered in various ways – made taller, smaller or stripped of original ornaments, often after damage in various wars, when restoration would have proved too expensive. In the end, they have become mutts and mongrels of architecture.

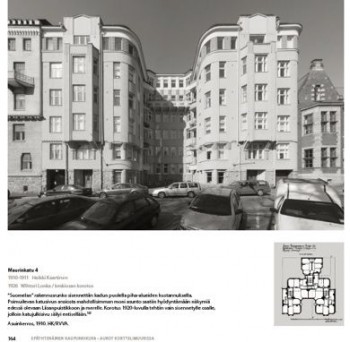

Upwards: an extra floor was added to the middle section of this apartment house (1910–11) in 1926.

Architect Juha Ilonen has wandered around Helsinki with his camera, capturing views that often take a Helsinki citizen by surprise.

In his new, capacious book Kolmas Helsinki – kerroksia arjen arkkitehtuurissa (‘The third Helsinki – layers in the architecture of the everyday’) Ilonen features ca. 300 buildings, from the mid-18th century to 2010. Most of them are apartment buildings situated in downtown Helsinki.

Why is it that I’ve never paid any attention to this or that extraordinary building, even though I hurry past it almost every day? Simply because I often don’t lift my gaze up from street level. The buildings speak volumes about history, aesthetics and demands of practicality.

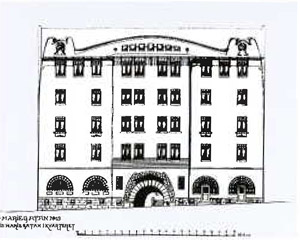

Mariankatu Street 19: original architecture by Gustaf Estlander, 1904–05

But take a look at this house in Kruununhaka in the heart of the city – Books from Finland resided in the back yard building for years, and we had absolutely no idea that the façade had been thoroughly altered and stripped of its beautiful Jugend ornaments…

Mariankatu Street 19: new version, by Ole Gripenberg, 1936

Ilonen’s book is a treasure trove for anybody interested in architecture, housing or city life – or photography: hundreds of black-and-white photographs feature delightful samples of the variety and quality of Helsinki architecture.

Juha Ilonen

Kolmas Helsinki – kerroksia arjen arkkitehtuurissa

The third Helsinki – layers in the architecture of the everyday]

Helsinki: AtlasArt, 2013. 304 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5671-51-3

€55, hardback

Indifference under the axe

9 March 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

In the forest: an illustration by Leena Krohn for her book, Sfinksi vai robotti (Sphinx or robot, 1999)

The original virtual reality resides within ourselves, in our brains; the virtual reality of the Internet is but a simulation. In this essay, Leena Krohn takes a look at the ‘shared dreams’ of literature – a virtual, open cosmos, accessible to anyone, without a password

How can we see what does not yet exist? Literature – specifically the genre termed science fiction or fantasy literature, or sometimes magic realism – is a tool we can use to disperse or make holes in the mists that obscure our vision of the future.

A book is a harbinger of things to come. Sometimes it predicts future events; even more often it serves as a warning. Many of the direst visions of science fiction have already come true. Big Brother and the Ministry of Truth are watching over even greater territories than in Orwell’s Oceania of 1984. More…

Is it a play, is it a book?

25 February 2011 | This 'n' that

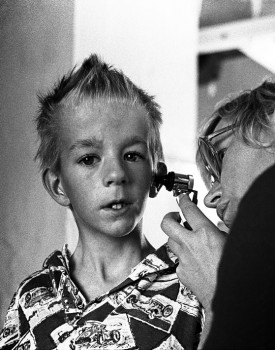

On the way to fame: Walt the Wonder Boy in Kristian Smeds's stage adaptation of Paul Auster's novel Mr. Vertigo at the Finnish National Theatre (2010). Photo: Antti Ahonen

Dramatisations of novels are tricky. Finnish theatremakers like adapting novels for the stage, which often results in a lot of talking instead of action – and action here doesn’t refer to just physical movement but to the subtext, to what happens under and behind the words.

Currently an adaptation of an American novel is running on the main stage of the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki. Mr Vertigo (1994), Paul Auster’s seventh book, tells the story of an orphan boy in the 1930s St Louis. After harsh years as the long-suffering apprentice of the mysterious Master Yehudi, Walt becomes the sensational Wonder Boy by learning how to levitate.

In theatremaker Kristian Smeds’s adaptation, Auster’s whimsical, rambling novel becomes a capricious, illusory journey about illusions, freedom, and the unattainability of love. Walt (the highly expressive, athletic Tero Jartti) interprets, with hilarious comedy as well as with touching desperation, both the dizzyingly powerful experience of creativity and the ridiculous hubris of the artist. More…

John Lagerbohm & al.: Me puolustimme elämää. Naiskohtaloita sotakuvien takaa [We were defending life. The fates of women behind pictures of war]

21 April 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

John Lagerbohm & Jenni Kirves & Olli Kleemola

John Lagerbohm & Jenni Kirves & Olli Kleemola

Me puolustimme elämää. Naiskohtaloita sotakuvien takaa

[We were defending life. The fates of women behind pictures of war]

Esipuhe [Foreword]: Elisabeth Rehn

Helsinki: Otava, 2010. 176 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-24660-2

€ 41, hardback

The women’s narratives of the Winter War (1939–40) and the Continuation War (1941–44) in this book are complemented by memoirs and academic writing, as well as journalistic extracts, personal recollections and interviews. It focuses on the status of women in wartime, showing that, in addition to the members of the Lotta Svärd auxiliary organisation, women carried a great deal of responsibility in a variety of roles, taking up traditionally male-dominated work in ports and mines. During the war years, the duty to work applied to all citizens aged 15 and up for whom various tasks could be assigned. One of the difficult jobs for ‘Lottas’ on the front line was placing the bodies of fallen soldiers into coffins and sending them home for burial. To maintain morale, it was important to the women to derive joy even from little things, and that humour comes through in this book as well. There is a wide range of photographic material, some of which comes from private collections.

Street-corner man

11 March 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographs from Caj Bremer. Valokuvaaja / Photographer / Fotograf (Musta Taide, 2010; graphic design by Jorma Hinkka)

The period after the Second World War and before the age of television was the golden age of photojournals such as Life, Look and Paris Match. The big Finnish illustrated periodical was Viikkosanomat (‘The weekly news’); its early star, Caj Bremer, was one of the first Finnish press photographers to wander among people and record life as it was

‘Every photograph is the sum of aesthetic choices, and each one has a relationship with reality both when it is taken and in the time frame in which the viewer encounters it’, writes news editor and curator Riitta Raatikainen in her introduction to Caj Bremer. Valokuvaaja / Photographer / Fotograf.

Caj Bremer (born 1929) worked for years as a press photographer, most intensively between 1950 and 1970. A retrospective exhibition of his work over six decades opened at Helsinki’s Ateneum Art Museum in February (until 16 May). More…

Högtärade Maestro! Högtärade Herr Baron! [Correspondence between Axel Carpelan and Jean Sibelius,1900–1919]

17 December 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Högtärade Maestro! Högtärade Herr Baron! Korrespondensen mellan Axel Carpelan och Jean Sibelius 1900–1919

Högtärade Maestro! Högtärade Herr Baron! Korrespondensen mellan Axel Carpelan och Jean Sibelius 1900–1919

[My dear Maestro! My dear Herr Baron! Correspondence between Axel Carpelan and Jean Sibelius, 1900–1919]

Red. [Ed. by] Fabian Dahlström

Helsinki: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, 2010. 549 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-583-200-9

€40, hardback

‘For whom shall I compose now?’ wrote Finnish composer Jean Sibelius in his diary upon hearing of the death of his good friend Axel Carpelan (1858 –1919). Carpelan was a penniless baron, who considered music and his friendship with Sibelius to be the most vital aspects of his life. Using his natural-born talent and instinct, he gained acceptance as Sibelius’ trusted musical confidant, to whom the composer dedicated his second symphony. Axel came to be known by the wider public in 1986, when his great-nephew, the author Bo Carpelan, made him the protagonist of his award-winning novel entitled simply Axel. This volume, edited by Fabian Dahlström, contains the surviving Swedish-language correspondence between Sibelius and Carpelan, as well as letters to Sibelius’ wife, Aino. Carpelan wrote to her when the composer was too busy. These letters contain interesting details such as Aino Sibelius’ account of the origins of her husband’s violin concerto. The comprehensive foreword to this book sheds additional light on Carpelan’s life.

Nordic prize to Sofi Oksanen

31 March 2010 | In the news

The Nordic Council’s Literary Prize 2010 has been awarded to Sofi Oksanen for her novel Puhdistus (‘Purge’, WSOY, 2008).

The winning novel was selected by a jury from a shortlist of 11 works from the Nordic countries. The prize, worth approximately 47,000 euros, will be awarded in Reykjavik in November.

The novel, about women’s fates in the violent history of 20th-century Estonia, was awarded both the Finlandia Prize for Fiction and the Runeberg Prize in Finland, where it has sold more than 142,000 copies.

So far publication rights have been sold to 27 countries; the English translation, by Lola Rogers, will appear next month in the US, published by Grove Press.

My friend Erik Hansen

Short prose from Muita hyviä ominaisuuksia (‘Other good characteristics’, Otava, 2010)

On the first day we played getting-to-know-you games. On the second day we played real Finnish baseball out behind the university. On the third day we travelled to the countryside. Classes started sometime at the end of the second week. We watched the movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The professor slurped Coke, chain smoked, and rewound the video back and forth: Nurse Ratched’s plump face filled the screen and then in the next image where her face had been there was a basketball Jack Nicholson was squeezing.

It was the autumn of 1992, and I was studying film and communications theory in Copenhagen.

The excursion to the country frightened me, a shy bacteriophobic neurotic. The Danes thought the camping centre’s shared mattresses and group cooking were hygge – cozy. There is no way a dictionary translation could ever cover all the forms of cosiness the Danes achieve together. I fled the camping centre on the first morning. On the train to Copenhagen I recognised all the usual post-escape feelings: shame, fear, guilt, loneliness and overwhelming euphoria. More…

Travelling alone

30 June 2005 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Ödemjuka belles lettres från en till en (‘Humble belles lettres from one to one’, Schildts, 2002)

Blind Alley Travel Bureau

We arrive on the last arrival.

Turn the lights out when you go, the airport staff ask.

To this place you and I must travel. It was the only departure

that was called. The only place there is, said the guide.

One’s vision is blocked by the view. We’ll find no somewhere else.

‘When I fall asleep, drive the last stretch by yourselves,’

says the driver.

A last summer family lift him into

their homeward-returning back seat. More…

Timeless time

30 December 2005 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Jumala saalistaa öisin eli Jobin kirjaan meidän on aina palaaminen. Osittain kursivoituja runoja (‘God hunts at night, or, we shall always return to the Book of Job. Partly italicised poems’, Otava, 2005)

Greek delights

I eat Giorgios D. Haniotis'

small joys

buried in powdered sugar,

vanilla, rose petal and strawberry,

as if wooing his three daughters,

reading Angelos Sikelianos' poem

'A country wedding':

and it is a beautiful blue day, Sunday,

the strange charm of Greek letters: i kiriaki,

hazelnut kernels dipped in thyme honey,

white herb ashes from the roadside,

a cigarette taste deep as sin,

tobacco smoke the only haze one can stand looking at,

a little quarrelsome noise, bus station flu,

promises made by Turks,

the threadbare pile carpet of the entrance hall as a word of honor, More…

Pig cheeks and chanterelle dust

21 August 2014 | This 'n' that

Wild and plentiful: chanterelles, black horns of plenty. Photo: Soila Lehtonen

Pop-up restaurants came into being in Helsinki in 2011: a few times every year any eager amateur cook is able to set up a ‘restaurant’ for one day on a street corner or in a park: citizens are welcome to take their pick, at a modest price.

In a northern city, not exactly suitable for street food trade all year round, in a country where rules of food hygiene are strict, the innovation of the Restaurant Day has been welcomed by the public. The latest event took place on 17 August.

The idea has now spread to at least 60 countries. Foodie culture thrives.

We find an article in The New Yorker by Adam Gopnik, No rules! Is Le Fooding, the French culinary movement, more than a feeling? interesting – according to comments quoted in it, ‘food must belong to its time’, and the traditional French cuisine ‘was caught in a museum culture: the dictatorship of a fossilized idea of gastronomy’.

In the 1960s, ‘nouvelle cuisine’, as opposed to cuisine classique, began to promote lighter, simpler, inventive, technically more advanced cooking. Well – some of us may remember that, at worst, this could also manifest itself in, say, three morsels of some edible substance placed decoratively on a plate topped with three chives: expensive, insubstantially elegant and pretty useless.

Today, Finland, the traditional stronghold of liver casserole, brown sauce and ham-mincemeat-pineapple pizzas (yes), seems to have moved onto a higher level of the culinary art – at least in selected restaurants. In a recent article, Helsinki’s food scene, coming on strong, published in The Washington Post, Tom Sietsema enjoys the pleasure of discovering things Finnish.

He is treated to parsnip leaves turned into ice cream imparting a coconut flavour, crackers made from leek ash and risotto in which ‘tiny green hops and their purple flowers interrupt the beige surface of the bowl, whose rim is dusted with golden chanterelle powder.’

The Executive Chef of Helsinki’s esteemed Savoy restaurant (est. 1937) cooks braised pig cheeks served with rhubarb and spring greens. A hunter-gatherer chef collects wild things: wood sorrel, spruce shoots and orpine and serves them in an omelette, with a drink made of chaga mushrooms (used for making tea; a sort of ‘sterile conk trunk rot of birch’, currently very much in vogue among the most eager of foodies for its medicinal [antioxidant, anti-inflammatory] properties).

It is true that Copenhagen and Stockholm have advanced further on their way to international fame of cuisine, but perhaps Helsinki will follow suit. And people who go out for a meal are no longer expected to settle for morsels with chives on top – food belongs to its time, and time changes food(ies).

A comment on Sietsema’s article claims though that his ‘verbiage’ has ‘nothing to do with what 99.999% of Finns eat! and what 99.99% of Finnish restaurants offer!’

But the truth (we know) is now closer to Sietsema than the commentator: ambitious restaurants may play with golden chanterelle powder, and even if it is not exactly what Finns often have for tea, we believe Finns today are losing interest in cheap chicken slivers in industrial marinade for dinner, and even beginning to accept that greens may not be only for bunnies.

Chanterelles have always been considered as a treat: fresh from the woods, quickly cooked in butter and cream, served with new potatoes and rye bread, or in an omelette: bon appetit (even without orpine)!

Autumn’s child

17 November 2011 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Bo Carpelan’s novel Blad ur höstens arkiv. Tomas Skarfelts anteckningar (‘Leaves from autumn’s archive. The notes of Tomas Skarfelt’). Introduction by Clas Zilliacus

When I took my first walk here in Udda, along the road down to the end of the bay, my legs wanted to go left up to the forest, while I strove to walk straight ahead. It was an unsteadiness reminiscent of being slightly drunk. A slight vertigo I have already noticed before. Trees soughed through me and the water of the bay tasted almost like salt on my lips. All sorts of things try to pass straight through me nowadays. I am becoming a general store. The few people I know go there and choose, and I try to sell. Most of it is old memories with attendant dust. They are in no chronological order at all, and make involuntary, rapid leaps, like kangaroos. Even when I went to school they hopped around. They forced me to learn my lessons by heart. They continued to skip over me at university and added an extra complexity to my studies in general history: concentrate of reign lengths.

And if I followed my legs and gave not a damn about my dead straight road? Digressions from what was planned provided me later on with my best experiences, and coincidences were grains of gold. Improvisations were lucky throws, or disasters. Afterwards came the restrictions, the constructions, the architecture. Now only that squared-paper notebook remains with its pitfalls. The uncertainty is sometimes imperceptible, but is there: Am I not superfluous? Are not my legs somewhat irrational? More…

All aboard

30 December 2005 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Nooakan parkki (‘Noahannah’s barque’, Tammi, 2005)

A Royal Navy Three-funnel Brig

The crew:

Matilda, an overeating cat

Five geese

20 hens

A fat narcoleptic cock

A couple of ducks

A goat

Three dogs

48 bats

Six woodpeckers

104 titmice

There’s a north-westerly blowing.

Djibouti 253

Three feet long from the east and five from the west, plus two hat-heights above the earth’s surface; standing on the sauna bench I scan the horizon for any omens – a raven, a woodpecker or a flock of waxwings. A crow would do. More…

The son of the chimera

30 September 1999 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Pereat mundus. Romaani, eräänlainen (‘Pereat mundus. A novel, sort of’, WSOY, 1998)

I was born, but not because anyone wanted it to happen. No one even knew it was possible, for my mother was a human being, my father a chimera. He was one of the first multi-species hybrids.

Only one picture of my father survives. It is not a photograph, but a water-colour, painted by my mother. My father is sitting in an armchair, book in hand, one cloven hoof placed delicately on top of the other. According to my mother, he liked to leaf through illustrated books, although he never learned to read. He is wearing an elegant, muted blue suit jacket, but no trousers at all. Thick grey fur covers his strong legs, right down to his hoofs. Small horns curve gracefully over his convex forehead. Striking in his face are his round, yellow eyes, his extraordinarily wide mouth, his tiny chin and his surprisingly large but flat nose. More…