Search results for "Riikka Pulkkinen/2010/10/riikka-pulkkinen-totta-true/2011/04/matti-suurpaa-parnasso-1951–2011-parnasso-1951–2011"

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2013

14 November 2013 | In the news

One of the following six novels will be awarded this year’s Finlandia Prize for Fiction, worth 30,000 euros: Ystäväni Rasputin (’My friend Rasputin’) by JP Koskinen, Hotel Sapiens (Teos) by Leena Krohn, Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday life’, Teos) by Riikka Pelo, Terminaali (‘The terminal’, Siltala) by Hannu Raittila, Herodes (‘Herod’, WSOY) by Asko Sahlberg and Hägring 38 (‘Mirage 38’, Schildts & Söderströms; Finnish translation, Kangastus, Otava) by Kjell Westö.

Half of the writers have already won the Finlandia Prize once, namely Krohn (1992), Raittila (2001) and Westö (2006).

Four of the six works deal with a historical character or history: Koskinen with the Russian ‘holy man’ Rasputin, Pelo with the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, Sahlberg with Herod the Great of Judea. Westö goes back to the year 1938 in Finland.

Raittila’s realistic novel takes place on contemporary airports. Krohn, again taking a look at an unknown future, presents the reader with a imaginary Earth which no longer is habitable to humans.

The runners-up were chosen by a jury – appointed by the Finnish Book Publishers’ Association – of three: the journalists Nina Paavolainen and Raisa Rauhamaa and the translator Juhani Lindholm. The winner of the 30th Finlandia Prize for Fiction will chosen by theatre manager of the Helsinki City Theatre and actor Asko Sarkola, and announced on 3 December.

3 x Runeberg: poet, cake & prize

5 February 2014 | This 'n' that

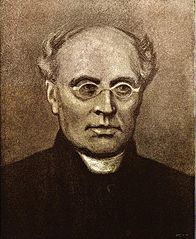

J.L. Runeberg. Painting by Albert Edelfelt, 1893. WIkipedia

Today, the fifth of February, marks the birthday of the poet J.L. Runeberg (1804–1877), writer, among other things, of the words of Finnish national anthem.

Runeberg’s birthday is celebrated among the literary community by the award of the Runeberg Prize for fiction; the winner is announced in Runeberg’s house, in the town of Borgå/Porvoo.

Runeberg’s favourite. Photo: Ville Koistinen

Mrs Runeberg, a mother of seven and also a writer, is said to have baked ‘Runeberg’s cakes’ for her husband, and these cakes are still sold on 5 February. Read more – and even find a recipe for them – by clicking our story Let us eat cake!

The Runeberg Prize 2014, worth €10,000, went to Hannu Raittila and his novel Terminaali (‘Terminal’, Siltala).

Hannu Raittila. Photo: Laura Malmivaara

According to the members of the prize jury – the literary scholar Rita Paqvalen, the author Sari Peltoniemi and the critic and writer Merja Leppälahti – they were unanimous in their decision; however, the winner of the 2013 Finlandia Prize for Fiction, Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday lives’) by Riikka Pelo, was also seriously considered.

Read more about the 2014 Runeberg shortlist In the news.

Make or break?

17 November 2011 | This 'n' that

Two tax collectors: anonymous painter, after Marinus van Reymerswaele (ca. 1575–1600). Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy. Wikimedia

In Finland, tax returns are public information. So, every November the media publish lists of the top earners in Finland, dividing them into the categories of earned and investment income. Every November it is revealed who are millionaires and who are just plain rich.

The Taloussanomat (‘The economic news’) newspaper offers a list (Finnish only) of the 5,000 people who earned most last year (in terms of both earned and investment income, together with the proportion of income they have paid in tax). You can also search lists of various status and professions: rock/pop stars, media, sports, MPs, celebrities, politicians of various political parties…

So let’s take a look at Taloussanomat’s selected list of authors: number one is the celebrity author Jari Tervo (309,971 euros, tax percentage 45); number two, the internationally famous Sofi Oksanen (302,634 euros, 46 per cent); the next two are Sinikka Nopola, writer of children’s books, (264,000) and Arto Paasilinna (262,300; now after an illness, retired as a writer), translated into more than 30 languages since the 1970s. (The film critic and author Peter von Bagh made almost 900,000 euros – not by writing books, but by selling his share of a music company to an international enterprise.)

As tax data are public in Finland, there’s vigorous and decidedly informed public debate on how much money, for example, directors of public pension institutions and government offices or ministers and other top politicians are paid, and how much they should be paid: what is equitable, what is reasonable? A million dollar question indeed…

Among the European Union countries, it is only in Finland, Sweden and Denmark that there is no universal minimum wage. Here, wages are determined in trade wage negotiations. The average monthly salary in the private sector in 2010 was approximately 3,200 euros. In contrast to that, Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, the Nokia CEO and President, who tops the 2010 tax list, earned a salary of 8 million last year, because – and precisely because – he was sacked (and replaced by the Irishman Steven Elop).

The CIA’s Gini index measures the degree of inequality in the distribution of family income in a country. The more unequal a country’s income distribution, the higher is its Gini index. The country with the highest number is Sweden, 23; the lowest, South Africa, 65 (data from both, 2005). Finland’s figure is 26.8 (2008), Germany 27 (2006), the European Union’s 34. The United Kingdom stands at 34 (2005), and the USA at 45 (2007). The figure in Finland seems to be on the rise though, as the figure back in 1991 was 25.6.

There’s been plenty of research and debate on economic inequality and the ways it harms societies. This link takes you to a fascinating video lecture (July 2011 – now seen by almost half a million people) by Richard Wilkinson, British author, Profefssor Emeritus of social epidemiology.

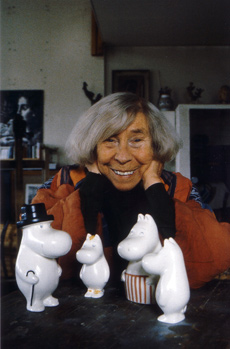

Hip hip hurray, Moomins!

22 October 2010 | This 'n' that

Partying in Moomin Valley: Moomintroll (second from right) dancing through the night with the Snork Maiden (from Tove Jansson’s second Moomin book, Kometjakten, Comet in Moominland, 1946)

The Moomins, those sympathetic, rotund white creatures, and their friends in Moomin Valley celebrate their 65th birthday in 2010.

Tove Jansson published her first illustrated Moomin book, Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen (‘The little trolls and the big flood’) in 1945. In the 1950s the inhabitants of Moomin Valley became increasingly popular both in Finland and abroad, and translations began to appear – as did the first Moomin merchandise in the shops.

Jansson later confessed that she eventually had begun to hate her troll – but luckily she managed to revise her writing, and the Moomin books became more serious and philosophical, yet retaining their delicious humour and mild anarchism. The last of the nine storybooks, Moominvalley in November, appeared in 1970, after which Jansson wrote novels and short stories for adults.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a painter, caricaturist, comic strip artist, illustrator and author of books for both children and adults. Her Moomin comic strips were published in the daily paper the London Evening News between 1954 and 1974; from 1960 onwards the strips were written and illustrated by Tove’s brother Lars Jansson (1926–2000).

Tove’s niece, Sophia Jansson (born 1962) now runs Moomin Characters Ltd as its artistic director and majority shareholder. (The company’s latest turnover was 3,6 million euros).

For the ever-growing fandom of Jansson there is a delightful biography of Tove (click ‘English’) and her family on the site, complete with pictures, video clips and texts.

The world now knows Moomins; the books have been translated into 40 languages. The London Children’s Film Festival in October 2010 featured the film Moomins and the Comet Chase in 3D, with a soundtrack by the Icelandic artist Björk. An exhibition celebrating 65 years of the Moomins (from 23 October to 15 January 2011) at the Bury Art Gallery in Greater Manchester presented Jansson’s illustrations of Moominvalley and its inhabitants.

In association with several commercial partners in the Nordic countries Moomin Characters launched a year-long campaign collecting funds to be donated to the World Wildlife Foundation for the protection of the Baltic Sea. Tove Jansson lived by the Baltic all her life – she spent most of her summers on a small barren island called Klovharu – and the sea featured strongly in her books for both children and adults.

Comic prize

26 March 2010 | In the news

Sarjakuva-Finlandia, worth €5,000, is the name of a prize created in 2007 for Finnish graphic novels or comic books. (Sarjakuva, literally ‘serial picture’, refers to both comic strips and books as well as graphic novels.)

It is awarded annually at the Tampere comics festival (and has nothing to do with the Finlandia prizes for literature, awarded by the Finnish Book Foundation).

Out of 56 contestants, ten made it into the final run, and the winner, Eero, by Petteri Tikkanen, was chosen by the thriller writer Matti Rönkä.

Petteri Tikkanen (born 1975) is a graphic artist who has published several books. In his previous graphic novels about a girl named Kanerva, Eero has appeared as her friend. Now Eero is the central character, and it seems childhood is over. Kanerva likes to chill out with her girlfriends only – what is a boy to do?

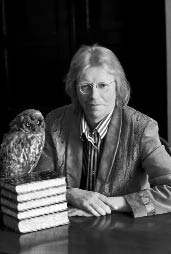

Henrik Meinander: Kekkografia. Historiaesseitä [Kekkography. History essays]

1 April 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kekkografia. Historiaesseitä

Kekkografia. Historiaesseitä

[Kekkography. History essays]

Suomentanut [Translated into Finnish from the original Swedish texts by] Matti Kinnunen

Helsinki: Siltala, 2010. 229 p.

ISBN 978-952-234-040-5

€ 34, hardback

Professor Henrik Meinander examines the forces that have shaped Finnish history and the controversial issues that have marked its development; Finnish history and culture were formed by chain reactions in European power politics. Finland did not emerge as a nation until the 19th century, as a by-product of the Napoleonic wars, and the independence of 1917 was not the result of an autonomous process of national development but rather a consequence of events elsewhere, especially in Russia. The history of independent Finland is roughly equal in length to that of the Soviet Union; in the early 1990s the Soviet Union collapsed, and Finland joined the European Union. The author does not take a position on the desirability of this development, and points out that the increasing integration and globalisation Finland’s era of independence may appear to be only a transitory phase. President Urho Kekkonen (1900–1986), who influenced Finnish politics for half a century and whose name gives the work its title, figures in approximately half of the texts.

Translated by David McDuff

Grim(m) stories?

30 April 2010 | Letter from the Editors

‘There’s not been much wit and not much joy, there’s a lot of grimness out there.’

‘There’s not been much wit and not much joy, there’s a lot of grimness out there.’

This comment on new fiction could have been presented by anyone who’s been reading new Finnish novels or short stories. The commentator was, however, the 2010 British Orange Prize judge Daisy Goodwin, who in March complained about the miserabilist tendencies in new English-language women’s writing. More…

In with the new?

17 December 2010 | Letter from the Editors

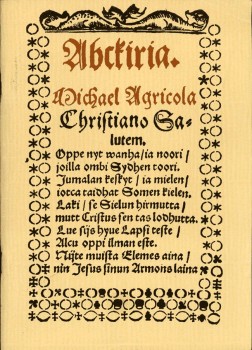

Abckiria (‘ABC book’, 1543): the first Finnish book, a primer by the Reformation bishop Mikael Agricola, pioneer of Finnish language and literature

In August 2010 the American Newsweek magazine declared Finland (out of a hundred countries) the best place to live, taking into account education, health, quality of life, economic dynamism and political environment.

Wow.

In the OECD’s exams in science and reading, known as PISA tests, Finnish schoolchildren scored high in 2006 – and as early as 2000 they had been best at reading, and second at maths in 2003.

Wow.

We Finns had hardly recovered from these highly gratifying pieces of intelligence when, this December, we got the news that in 2009 Finnish kids were just third best in reading and sixth in maths (although 65 countries took part in the study now, whereas in 2000 it had been just 32; the overall winner in 2009 was Shanghai, which was taking part for the first time.)

And what’s perhaps worse, since 2006 the number of weak readers had grown, and the number of excellent ones gone down. More…

Below and above the surface

13 March 2014 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Fårö, Gotland, Sweden. Photo: Lauri Rotko

The Baltic Sea, surrounded by nine countries, is small, shallow – and polluted. The condition of the sea should concern every citizen on its shores. The photographers Jukka Rapo and Lauri Rotko set out in 2010 to record their views of the sea, resulting in the book See the Baltic Sea / Katso Itämerta (Musta Taide / Aalto ARTS Books, 2013). What is endangered can and must be protected, is their message; the photos have innumerable stories to tell

We packed our van for the first photo shooting trip in early May, 2010. The plan was to make a photography book about the Baltic Sea. We wanted to present the Baltic Sea free of old clichés.

No unspoiled scenic landscapes, cute marine animals, or praise for the bracing archipelago. We were looking for compelling pictures of a sea fallen ill from the actions of man. We were looking for honesty. More…

A rare bird from Fancyland

20 August 2013 | Reviews

Bead-covered curlew, 1960. Height ca. 115 cm, Collection Kakkonen. Photo: Niclas Warius

Harri Kalha:

Birger Kaipiainen

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (The Finnish Literature Society), 2013. 249 p., ill.

(Summaries in Swedish and English)

ISBN 978-952-222-457-6

€46, hardback

Ceramics confectioner. Degenerate aristocrat. Ornamental criminal. These epithets can be found in Birger Kaipiainen, a new, full-length study of the ceramic artist by art historian Harri Kalha.

Throughout his artistic career Birger Kaipiainen (1915–1988) worked with forms, subjects and methods that were unfamiliar in the field of traditional ceramics, at least in mid-20th-century Finland, and made use of fantasy and ornament. As a ‘porcelain painter’ he showed little interest in the technical challenges of clay – although in his ceramic creations Kaipiainen explored three-dimensional form, montage, colour, texture and the tactile dimensions of the medium. More…

What Finland read in February

28 March 2013 | In the news

Artist and painter Hannu Väisänen (born 1951) began writing an autobiographical series of novels in 2004. Born in the northern town of Oulu, he colourfully described his somewhat bleak childhood in a family of five children headed by a widowed soldier father. His fourth novel, Taivaanvartijat (‘The guardians of heaven’, Otava), is number one on the February list of best-selling Finnish fiction titles compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association.

Number two is former number one, the Finlandia Prize -winning novel Is (‘Ice’, in Finnish Jää; also to be published in English, possibly later this year) by Ulla-Lena Lundberg.

The latest comic book by Pertti Jarla about the inhabitants of Fingerpori (‘Fingerborg’, Arktinen Banaani), Fingerpori 6, was number three.

In first and second place on the translated fiction list were Stephen King – (11/22/63) and J.R.R. Tolkien (The Hobbit or There and Back Again).

At the top of the non-fiction list is, for the second time, Kaiken käsikirja (‘Handbook of everything’, Ursa) by astronomer and popular writer Esko Valtaoja. In these hard times Finns seems also to be interested in economics, so number two was Talous ja utopia (‘Economics and utopia’, Docendo) by Sixten Korkman, professor and specialist in international and national economics.

Juhani Suomi: Mannerheim – viimeinen kortti? Ylipäällikkö-presidentti [Finland plays its last card – Mannerheim, Commander-in-chief and President]

30 April 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Mannerheim – viimeinen kortti? Ylipäällikkö-presidentti

Mannerheim – viimeinen kortti? Ylipäällikkö-presidentti

[Finland plays its last card – Mannerheim, Commander-in-chief and President]

Helsinki: Siltala, 2013. 836 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-234-172-3

€32, hardback

In his book Professor Juhani Suomi – well-known as the biographer of President Urho Kekkonen – focuses on the life and actions of Marshal Gustaf Mannerheim (1867–1951) during the final phase of the Continuation War between Finland and the Soviet Union beginning in1943 and, in particular, during his term as Finnish President from 1944 to 1946. Mannerheim was elected President by exceptional procedure, and his difficult task was to lead Finland from war to peace, which he succeeded in doing. Suomi seeks to reply specifically to the question of whether Mannerheim lived up to the myth that was created about him, and of whether he was Finland’s last chance as the guarantor of the country’s independence during those fateful years, as he is often presented. On the basis of a number of sources, the author draws a critical portrait of an aristocrat: this was a man who was cold and vain, who at every turn thought mainly of his own posthumous reputation and who as an elderly leader was slow and fickle in his decisions – though the reader will not necessarily agree with all of Suomi’s conclusions. Well-written, occasionally a bit too detailed, his book vividly describes a dramatic period in Finland’s recent history.

Translated by David McDuff

Renaissance man

30 September 1990 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Bruno (WSOY, 1990)

Since her first collection of poems, which appeared in 1975, Tiina Kaila (born 1951 [from 2004, Tiina Krohn]) has published four children’s books and three volumes of poetry. Her novel Bruno is a fictive narrative about the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in 1600. It is the conflict inherent in her main character that interests Kaila: his philosophical and scientific thought is much closer to that of the present day than, for example, that of Copernicus, and it is this that led him to the stake; and yet he did never abandon his fascination for magic.

The novel follows Bruno on his journeys in Italy; France, Germany and England, where he is accompanied by the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau. Bruno finds England a barbaric place: ‘…These people believe that it is enough that they know how to speak English, even though no one outside this little island understands a word. No civilised language is spoken here’

In the extract that follows, Bruno, approaching the chalk cliffs of Dover by sea, makes what he feels to be a great discovery: ‘Creation is as infinite as God. And life is the supremest, the vastest and the most inconceivable of all.’

![]()

I was leaning on the foredeck handrail, peering into a greenish mist. The bow was thrashing between great swells, blustering and hissing and shuddering like some huge wheezing animal: Augh – aagh – ho-haugh! Augh – aagh – ho-haugh!

Plenty of space had been reserved for our use on this new two-master cargo boat. Castelnau was transferring his whole family from France – his wife, his daughter, his servants, his library, his furniture, his past and me – to London, where, as you know, he had been appointed Ambassador of France. More…