Search results for "2010/02/2009/09/what-god-said"

The Vatican

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Maan ja veden välillä (‘Between land and water’, 1955). Introduction by Pirkko Alhoniemi

At the top of the hill there was a cow barn with all kinds of trash scattered along its walls: rusty pails, pottery shards, old shoes, all the stuff country people toss onto rubbish heaps. The clucking of chickens and bleating of sheep filled the air. As I was running across the barnyard I had an idea that a chicken had probably just laid an egg on the grass or was looking for some place to lay an egg, because it was letting out such sharp scolding cries.

Many of us were running across the yard and in back of the cow barn. If I hadn’t been on my way to the Vatican I would have stayed to pat a calf that was rubbing its side against a wall of the cow barn in the glow of the rising sun. But I was in a hurry. I didn’t dare let the women out of my sight because I couldn’t find the way by myself, I couldn’t even remember exactly where I had joined the crowd. I had just seen them running by and while I hadn’t intended to start off for the Vatican just that day, I went along with them anyway. More…

The sea so open

30 September 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Delta (Teos, 2008). Introduction by Jukka Koskelainen

Like wave-polished stones

we sit on a seashore rock, shading our eyes

from the sun, each other, the deltoid sails, the water.

You ask nothing more,

you know the sum of the angles of a triangle,

that you have your sides, as I do

sometimes they near each other

as if to penetrate each other, cut

a hole in the landscape.

A seagull settles on a crag,

without a glance aside, you’re up and disappear

from my side.

Sails, other sails.

the sea so open and the sky open. More…

On the waves of our skin

4 December 2009 | Fiction, poetry

The poems in Ilpo Tiihonen’s new collection, Jumalan sumu (‘God’s mist’) – about fakirs, beggars, poets, lovers and life – are tinged with a gentle sense of the ephemerality of human life (see Gatecrashing the universe)

Poems from Jumalan sumu (‘God’s mist’, WSOY, 2009)

SANTO PAN

These mornings when beggars

station themselves at church doors

and a little grace slips through

the fingers of some of us,

it seems for a moment good

That crows are flying about

and princes’ bones are clattering in huge sarcophagi

And now, with a basic shape planned

for the daily bread,

Early morning wakes up in Florence

with black flour in its fingernails More…

Power or weakness?

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the play Hypnoosi (‘Hypnosis’, 1986). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

As you all know, this company has been my life’s work and it stands for everything I’ve had to renounce. You know that for years I have not received a penny for my personal expenses, that I am on the firm’s lowest wage level, zero.

I haven’t even had a free cup of coffee; if, because I have been working hard or I wanted to improve my concentration, I have felt like a cup of coffee, I have always gone to the canteen during my coffee break and challenged one of the boys to a bout of arm wrestling under the agreement that the loser buys the coffees, and the bloke has paid. The money never came out of the firm’s running expenses, investments, trusts or funds. More…

Troubled by joy?

30 September 1998 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Boxtrot (WSOY, 1998)

Nine lives

So far nine lives only, and

all mine, like my head in my hands.

My first was curled up at the foot of a fir tree

in the autumn forest just at day-dawn

in nighttime's raindrops.

The resin's still in my fingernails.

My second was the scent of split wood by the shed,

and the circular-saw blade's horrific disc.

The gruel, track shoes too large, and President Kekkonen,

ink spreading across my notebook, and

the clank of the railway under my dreams.

Mayday's red flags, the neighbour's daughter

naked, and dead pigeons lying on the gravel.

My third life was the discovery of anger, blind rage

turning and turning me in its leather bag,

wearing the edges of my day down. Sitting at our schooldesks

being forced towards a goal that can't be named.

Seeing how they start drinking, drinking

into their eyes that black impotent rebellion.

I'm on the point of drowning, someone's traversing

the Atlantic in a reed boat. And if I did die,

it wouldn't matter who sneered. The stars in the sky

are watching us in horror.

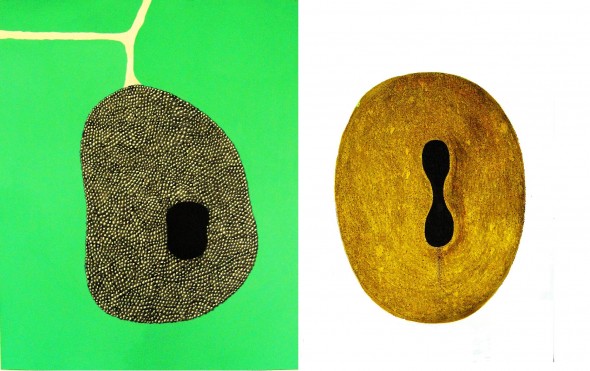

Green thoughts

Extracts from the novel Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, Otava, 2010)

I decided to go to the Museum of Fine Arts.

After paying for my entrance ticket, I climbed the wide staircase to the first floor. There all I saw were dull paintings, the same heroic seed-sowers and floor-sanders as everywhere else. Why were so many art museums nothing more than collections of frames? Always national heroes making their horses dance, mud-coloured grumblers and overblown historical scenes. There was not a single museum in which a grandfather would not be sitting on a wobbly stool peering over his broken spectacles, interrogating a young man about to set off on his travels, cheeks burning with enthusiasm, behind them the entire village, complete with ear trumpets and balls of wool. The painting’s eternal title would be ‘Interrogation’ and it would be covered with shiny varnish, so that in the end all you would be able to see would be your own face.

I climbed up to the next floor. All I really felt was a pressing need to run away. No Flemish conversation piece acquired in the Habsburg era was able to erase a growing anxiety related to love. More…

Sensitivity session

30 June 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Taito Suutarinen knew quite a bit about Freud. Where Mannerheim’s statue now stands, Taito felt that there ought instead to be an equestrian statue of Sigmund Freud. It would be like truth revealed.

Freud, urging on his trusty stallion Libido, would be clad from head to foot in sexual symbols – hat, trousers, shoes: one hand thrust deep into his pocket, the other grasping a walking-stick. The stick would point eloquently in the direction of the railway tracks, where the red trains slid into the arching womb of the station.

Taito had also attended a couple of seven-day sensitivity training courses, where people expressed their feelings openly, directly and spontaneously. By the end of the first course Taito was so direct and spontaneous that he couldn’t get on with anybody. By the end of the second he was so open that everyone was embarrassed. Every member of the group had cried at least once, except the group leader. Never before had Taito witnessed such power. He could not wait to found a group of his own. Taito’s group met in a basement room, where they reclined on mattresses to assist the liberation process. Everyone was free to have problems, quite openly. You were not regarded as ill: on the contrary, if you realized your problem you were more healthy than a person who still thought he mattered. Moreover, as Taito, fixing you with his piercing gaze, was always careful to emphasize, every problem was ultimately a sexual problem. Taito would spontaneously scratch his crotch as he spoke, making it clear that he himself had virtually no problems left. More…

Emotional transgressions

31 December 1985 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Three extracts from the novel Harjunpää ja rakkauden lait (‘Harjunpaa and the laws of love’). Introduction by Risto Hannula

It was a few minutes to two, and Harjunpää was still awake, lying so close to Elisa that he could feel her warmth. He kept his eyes open, staring into the night through the crack between curtains. Once again the boiler of the central heating plant started up, and the smoke began to rise like a stiff column in the cold. Another fifteen minutes had passed, and morning was a quarter of an hour closer. He squeezed his eyes shut and tried to concentrate on Elisa’s breathing and the sleepy snuffling of the girls, but his thoughts still wouldn’t leave him in peace. Inexplicably, he felt there was something wrong, that the darkness exuded some kind of threat, that he’d left something undone or had made some kind of mistake.

He swung his feet onto the floor and got up as quietly as he could. But all his care was wasted, he should have known that.

‘What’s the matter?’ Elisa asked sleepily.

‘I just can’t get to sleep.’

‘Again … ‘

‘I can’t help it. I wonder if there’s a bottle of brew left.’

‘Sure. But listen …’

Pipsa turned over in her crib, rattling the sides, groped around a bit and began to suck her pacifier so you could hear the quiet sucking noises.

‘Yeah?’

‘Maybe you could see a doctor. You could ask for some mild … ‘ More…

Fight Club

16 April 2012 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from Himokone (‘Lust machine’, WSOY, 2012). Interview by Anna-Leena Ekroos

Karoliina wondered whether her name was suitable for a famous poet.

Her first name was alright – four syllables, and a bit old-fashioned. But Järvi didn’t inspire any passion. Should she change her name before her first collection came out? Was there still time? She had four months until September.

Even if The flower of my secret was the name of some old movie, Karoliina clung to the title she’d chosen. It described the book’s multifaceted, erotically-tinged sensory world and the essential place of nature in the poems. Karoliina loved to take long walks in the woods. Sometimes she talked to the trees.

She had been meeting new people. At the writer’s evening organised by her publisher, she’d been seated next to Märta Fagerlund, in the flesh. Karoliina had read Fagerlund’s poems since her teens, and seen her charisma light up the stage on cultural television shows.

At first Karoliina couldn’t get a word out of her mouth. She just blushed and dripped gravy on her lap. But the longer the evening went on, the more ordinary Märta seemed. She was even calling her Märta, and telling her about a new friend on Facebook who said how ‘awfully funny’ Märta was. In fact, the squeaky-voiced Märta, with her enthusiasm for Greece, was a bit dry, and, after three glasses of white wine, tedious. But Karoliina never mentioned it to anyone, because she wasn’t a spiteful person. More…

The love of the Berber lion

30 December 2008 | Fiction, Prose

A short story from the novel Berberileijonan rakkaus ja muita tarinoita (‘The love of the Berber lion and other stories’, WSOY, 2008). Introduction by Janna Kantola

The lion’s name was Muthul. He was an old Berber lion from the Atlas Mountains. He had a black mane, a black tail with a bushy tip and the scars of many battles on his hide.

He had grown up as a lion cub in the royal palace at Carthage at the time when the Romans, led by Scipio the younger, destroyed the city with fire and sword. The palace was set ablaze, a bloody battle ensued in the gardens, Romans impaled on arrows lay strewn in the rose bushes, Carthaginian blood dyed the water in the fountains. Someone had let all the palace animals, wild and tame alike, out of their cages; they were running around wildly, killing each other in the grip of panic, then disappeared inexplicably. More…