Search results for "2010/02/2011/04/2009/09/what-god-said"

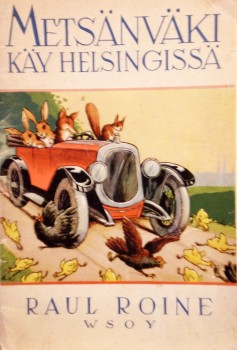

The forest folk’s trip to Helsinki

26 March 2015 | Children's books, Fiction

The country comes to town in this coyly modern fairy story of 1937 by the classic children’s writer Raul Roine (1907-1960). Reynard the Fox, the village taxi-driver, celebrates restoring his beat-up old Ford by taking his woodland friends – squirrels, chaffinches, bobtails… – on a day out to Helsinki. Trouble starts when a policeman tells them off for eating the plants in the Esplanade park, but the fun really begins when the hares find themselves participating in the marathon which is being run through the city streets that day…

The country comes to town in this coyly modern fairy story of 1937 by the classic children’s writer Raul Roine (1907-1960). Reynard the Fox, the village taxi-driver, celebrates restoring his beat-up old Ford by taking his woodland friends – squirrels, chaffinches, bobtails… – on a day out to Helsinki. Trouble starts when a policeman tells them off for eating the plants in the Esplanade park, but the fun really begins when the hares find themselves participating in the marathon which is being run through the city streets that day…

The translation of this delectable tale is by Books from Finland’s long-time collaborator Herbert Lomas (1924-2011), who was often at his best when working on the whimsy of children’s literature.

Spring had come to the forest homeland. The wood anemones were raising their heads shyly from under the moss, large tears of joy were flowing down the spruce trees’ beards of lichen, and sky-ploughs of cranes were coming from the south. They bugled mightily on their trumpets and then landed in the Great Marsh to sample the cranberries More…

Kullervo

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the tragedy Kullervo (1864). Introduction by David Barrett

The plot of the Kullervo story as told in the Kalevala: Untamo defeats his brother Kalervo’s army, and Kalervo’s son Kullervo is born a slave. Untamo sells him as a young child to llmarinen whose wife, the Daughter of Pohjola, makes the boy a shepherd and bakes him a loaf with a stone inside it. Kullervo takes his revenge by sending home a flock of wild animals, instead of cattle, who tear her to pieces. He flees, and discovers that his parents and two sisters are alive on the borders of Lapland. He finds them, but one of his sisters is lost. Life in the family home is unhappy: Kullervo fails in all the tasks his father sets him. On his way home one day he finds a girl in the forest whom he abducts in his sledge and seduces. It turns out the girl is his lost sister, who drowns herself when she learns that Kullervo is her brother. Kullervo sets out to revenge himself on Untamo; he kills and destroys. When he returns home, he finds the house empty and deserted, goes into the forest and falls on his sword.

ACT II, Scene 3

Kalervo’s cottage by Kalalampi Lake. It is night-time. Kimmo, seated by a fire of woodchips, is mending nets. More…

Money makes the world go round

31 August 2012 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mr. Smith (WSOY, 2012). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I have a confession to make.

I couldn’t have lived on my salary. Most people would solve this by taking out a loan, living on credit. I’ve never lived in debt. Instead I’ve had to make my modest capital grow by investing it – through the company, of course, because irrespective of their colour governments generally understand companies better than small investors. You have to make money somewhere other than the Social Security Office.

Work doesn’t make money; money makes money.

You have to let money do the work.

This is nothing short of a profound human tragedy: most people are forced to waste the majority of their lives, to use it in the service of complete strangers, for unknown purposes, doing something for money that they would never do if they didn’t have to. The most shocking thing is that people actively seek out this state of affairs, strive towards it; it is a goal towards which society lends us its full support, no less.

Such wage slavery is called ‘work’. More…

Mole’s hole

31 March 1992 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Pikku karhun talviunet (‘The little bear’s winter dreams’, published posthumously in 1974, edited by Mirkka Rekola), prose fragments and fairy-tales. (See commentary by Soila Lehtonen)

Vauveli-Vau had grown up. She went round to Mole Hill and went into Mole’s Hole, so she could work in peace. As there are a lot of Mole’s Holes in the earth, no one had any idea where Vauveli-Vau had gone. They weren’t all that keen to know, as there’s always rather a lot to do in Mole’s Hole: pine cones and branches to be collected, trips to be made to the spring in the forest, an eye kept on Dottypot in the fire-embers, and at night you have to get up to see which bird it is that’s singing in the old rotten tree. But still more laboursome are the thick books in foreign languages and the pile of blank paper.

Quite a few days and nights had gone by before Vauveli-Vau was used to being in Mole’s Hole. During those days a lot of remarkable things occurred. A slug flourished his horns and muttered: ‘Who on earth would want to lie about in his cottage in fine weather like this?’ More…

Shards from the empire

5 February 2010 | Fiction, Prose

‘Imperiets skärvor’, ‘Shards from the empire’, is from the collection of short stories, Lindanserskan (‘The tightrope-walker’, Söderströms, 2009; Finnish translation Nuorallatanssija, Gummerus, 2009)

Gustav’s greatest passion is for genealogy. He dedicates his free time to sketching coats of arms; masses of colourful, noble crests.

Gustav asked me to do a translation. I sat for ten days trying to decipher a couple of pages from a Russian archive dating from the 1830s. Sentences like, With this letter, we hereby give notice of our gracious decision.‘

The intricate handwriting belonged to some collegiate registrar or other. Perhaps Gogol’s Khlestakov. More…

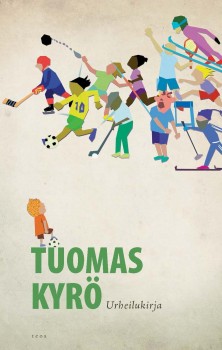

We are the champions

25 March 2011 | Prose

Heroes are still in demand, in sports at least. In his new book author Tuomas Kyrö examines the glorious past and the slightly less glorious present of Finnish sports – as well as the meaning of sports in the contemporary world where it is ‘indispensable for the preservation of nation states’. And he poses a knotty question: what is the difference, in the end, between sports and arts? Are they merely two forms of entertainment?

Heroes are still in demand, in sports at least. In his new book author Tuomas Kyrö examines the glorious past and the slightly less glorious present of Finnish sports – as well as the meaning of sports in the contemporary world where it is ‘indispensable for the preservation of nation states’. And he poses a knotty question: what is the difference, in the end, between sports and arts? Are they merely two forms of entertainment?

Extracts from Urheilukirja (‘The book about sports’, WSOY, 2011; see also Mielensäpahoittaja [‘Taking offence’])

The whole idea of Finland has been sold to us based on Hannes Kolehmainen ‘running Finland onto the world map’. [c. 1912–1922; four Olympic gold medals]. Our existence has been defined by how we are known abroad. Sport, [the Nobel Prize -winning author] F. E. Sillanpää, forestry, [Ms Universe] Armi Kuusela, [another runner] Lasse Viren, Nokia, [rock bands] HIM and Lordi, Martti Ahtisaari.

The purpose of sport at the grass-roots level has been to tend to the health of the nation and at a higher level to take our boys out into the world to beat all the other countries’ boys. We may not know how to talk, but our running endurance is all the better for it. However, the most important message was directed inwards, at our self image: we are the best even though we’re poor; we can endure more than the rest. Finnish success during the interwar period projected an image of a healthy, tenacious and competitive nation; political division meant division into good and bad, the right-minded and traitors to the fatherland. More…

Do you remember the yellow house?

14 February 2011 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Enkelten kirja (‘The book of angels’, Tammi, 2010)

[Tallinn, summer] The past will not go away

and the present is insurmountable. Summer vacation has begun, the newspaper hasn’t come; it doesn’t get delivered here anyway. Can you remember the Isabelline yellow house? Remember the alley with the name that means hurry? Surely you remember the home with all the maps on the shelves, the important papers and the brass objects bought from nearby antique dealers? Also the rugs from North Africa and the obligatory cedar camel figurines on the windowsill. And so many glasses and plates and empty lighters in a cardboard box on the shelf on the left hand side of the kitchen.

Tallinn, June 7th. The floors creak. One step has split in half; some of the lights have burned out. This is a lovely home. A small window upstairs is ajar to the courtyard. Tuomas had latched it behind the Virginia creepers. The fountain in the courtyard is dry. On cold nights the smoke from the fireplace grows like a statue for the crows until it wraps around over the layered rooftops like a snake eating its tail. Russian men are repairing the attic of the house across the street for wealthy people to live in; they laugh in front of the window and smoke. Tuomas waves at them, and they wave back. The courtyard is creepy when it’s empty. Soon the neighbours would go about their day and quietly close their doors behind them, and two nearby churches would divide the hours into quarters, Russians and their gossip would make their way to the Alexander Nevski Cathedral, and the Estonians and their gossip would go to their own churches where a wise and peculiar, almost human scent would rise from between the headstones. Tuomas wouldn’t smell it, Aino would and would move to stand beneath the the center tower. More…

The Vatican

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Maan ja veden välillä (‘Between land and water’, 1955). Introduction by Pirkko Alhoniemi

At the top of the hill there was a cow barn with all kinds of trash scattered along its walls: rusty pails, pottery shards, old shoes, all the stuff country people toss onto rubbish heaps. The clucking of chickens and bleating of sheep filled the air. As I was running across the barnyard I had an idea that a chicken had probably just laid an egg on the grass or was looking for some place to lay an egg, because it was letting out such sharp scolding cries.

Many of us were running across the yard and in back of the cow barn. If I hadn’t been on my way to the Vatican I would have stayed to pat a calf that was rubbing its side against a wall of the cow barn in the glow of the rising sun. But I was in a hurry. I didn’t dare let the women out of my sight because I couldn’t find the way by myself, I couldn’t even remember exactly where I had joined the crowd. I had just seen them running by and while I hadn’t intended to start off for the Vatican just that day, I went along with them anyway. More…

The sea so open

30 September 2008 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Delta (Teos, 2008). Introduction by Jukka Koskelainen

Like wave-polished stones

we sit on a seashore rock, shading our eyes

from the sun, each other, the deltoid sails, the water.

You ask nothing more,

you know the sum of the angles of a triangle,

that you have your sides, as I do

sometimes they near each other

as if to penetrate each other, cut

a hole in the landscape.

A seagull settles on a crag,

without a glance aside, you’re up and disappear

from my side.

Sails, other sails.

the sea so open and the sky open. More…

On the waves of our skin

4 December 2009 | Fiction, poetry

The poems in Ilpo Tiihonen’s new collection, Jumalan sumu (‘God’s mist’) – about fakirs, beggars, poets, lovers and life – are tinged with a gentle sense of the ephemerality of human life (see Gatecrashing the universe)

Poems from Jumalan sumu (‘God’s mist’, WSOY, 2009)

SANTO PAN

These mornings when beggars

station themselves at church doors

and a little grace slips through

the fingers of some of us,

it seems for a moment good

That crows are flying about

and princes’ bones are clattering in huge sarcophagi

And now, with a basic shape planned

for the daily bread,

Early morning wakes up in Florence

with black flour in its fingernails More…

The Tollander Prize to Ulla-Lena Lundberg

17 February 2011 | In the news

One of the biggest literary prizes in Finland is the Tollander Prize, awarded annually on 5 February, the birthday of he national poet J.L. Runeberg, by Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland). The prize is worth €35,000.

The recipient of the 2011 Tollander Prize is Ulla-Lena Lundberg, a versatile writer of novels, short stories, poems and travel essays. ‘She moves freely in different landscapes, times and cultures, finding universality in locality, whether on the island of Kökar in Åland, in Africa or in Siberia’, said the jury.

Written between 1989 and 1995, Lundberg’s fictional trilogy of Leo, Stora världen (‘The big world’) and Allt man kan önska sig (‘Everything one can wish for’), focused on the seafaring history and evolution of shipping in the Finnish Åland islands. Her autobiographical work Sibirien (Siberia’, 1993) has been published in German, Danish and Dutch.

Read the extracts from her latest book, Jägarens leende (‘Smile of the hunter’, 2010), on rock art, reviewed on our pages by Pia Ingström.

Power or weakness?

30 September 1986 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the play Hypnoosi (‘Hypnosis’, 1986). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

As you all know, this company has been my life’s work and it stands for everything I’ve had to renounce. You know that for years I have not received a penny for my personal expenses, that I am on the firm’s lowest wage level, zero.

I haven’t even had a free cup of coffee; if, because I have been working hard or I wanted to improve my concentration, I have felt like a cup of coffee, I have always gone to the canteen during my coffee break and challenged one of the boys to a bout of arm wrestling under the agreement that the loser buys the coffees, and the bloke has paid. The money never came out of the firm’s running expenses, investments, trusts or funds. More…